Algonquin Round Table on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Algonquin Round Table was a group of

The Algonquin Round Table was a group of

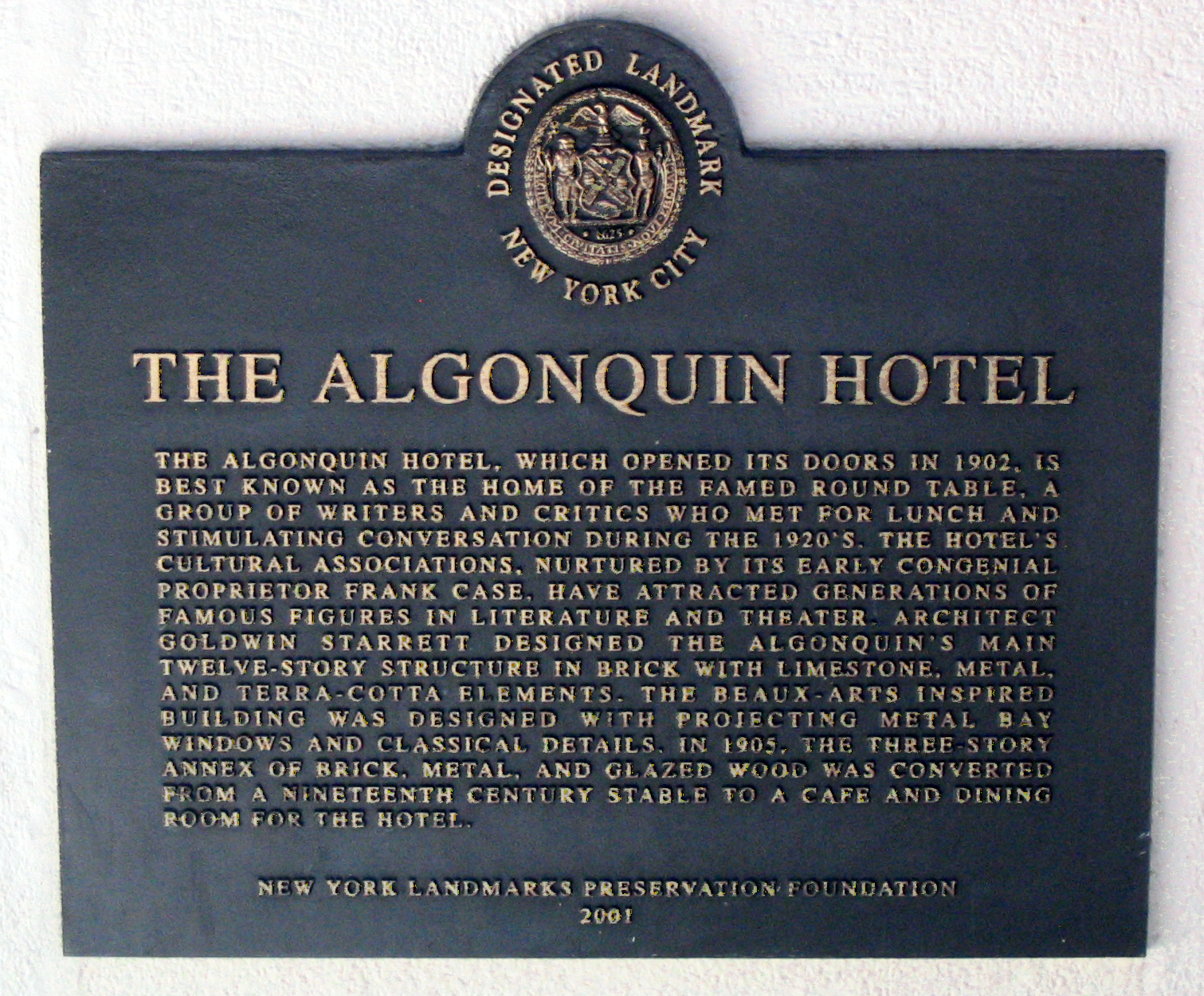

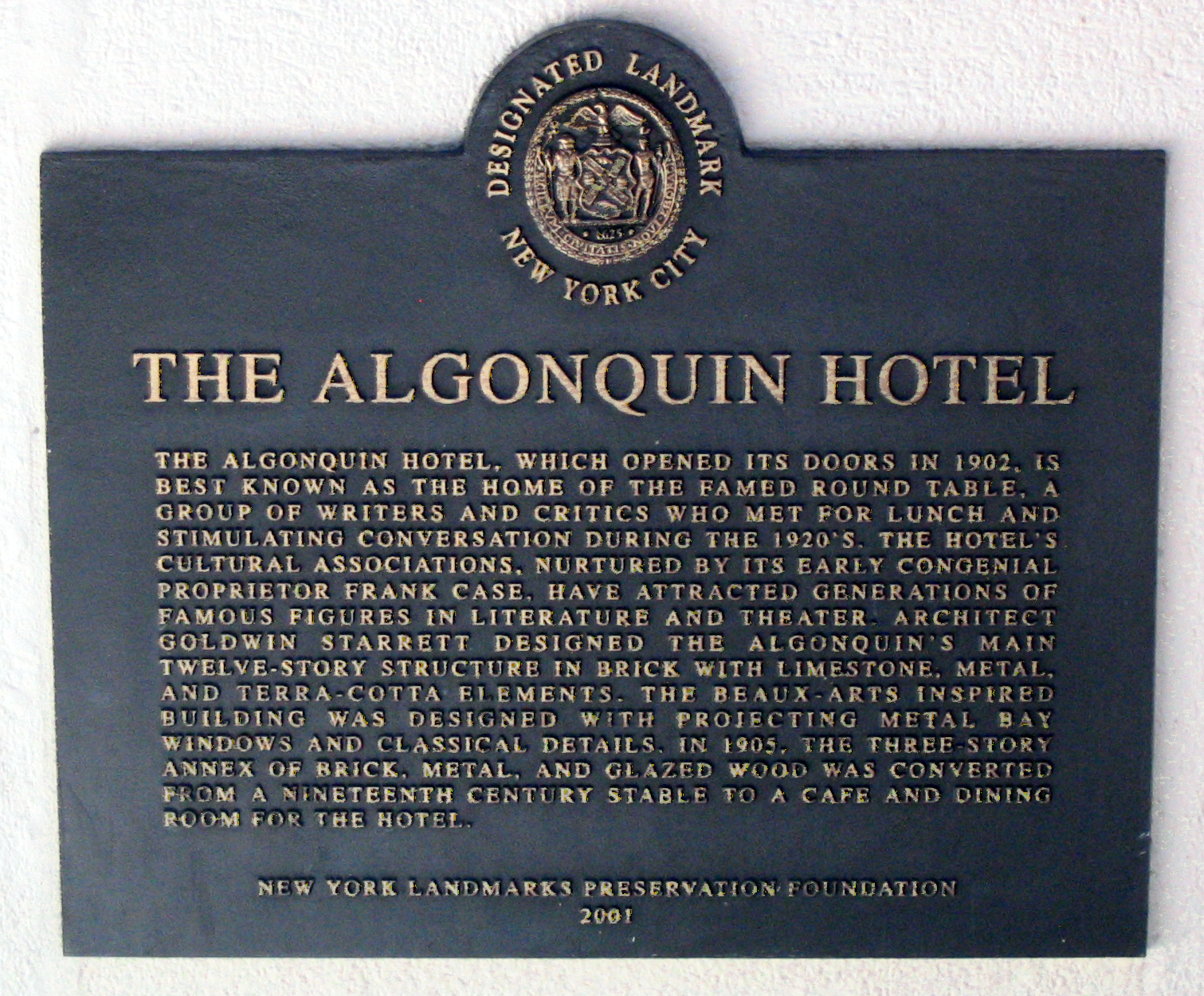

The Algonquin Round Table, as well as the number of other literary and theatrical greats who lodged there, helped earn the Algonquin Hotel its status as a New York City Historic Landmark. The hotel was so designated in 1987. In 1996 the hotel was designated a national literary landmark by the Friends of Libraries USA based on the contributions of "The Round Table Wits". The organization's bronze plaque is attached to the front of the hotel.

Although the Rose Room was removed from the Algonquin in a 1998 remodel, the hotel paid tribute to the group by commissioning and hanging the painting ''A Vicious Circle'' by Natalie Ascencios, depicting the Round Table and also created a replica of the original table. The hotel occasionally stages an original musical production, ''The Talk of the Town'', in the Oak Room. Its latest production started September 11, 2007 and ran through the end of the year.

A film about the members, '' The Ten-Year Lunch'' (1987), won the

The Algonquin Round Table, as well as the number of other literary and theatrical greats who lodged there, helped earn the Algonquin Hotel its status as a New York City Historic Landmark. The hotel was so designated in 1987. In 1996 the hotel was designated a national literary landmark by the Friends of Libraries USA based on the contributions of "The Round Table Wits". The organization's bronze plaque is attached to the front of the hotel.

Although the Rose Room was removed from the Algonquin in a 1998 remodel, the hotel paid tribute to the group by commissioning and hanging the painting ''A Vicious Circle'' by Natalie Ascencios, depicting the Round Table and also created a replica of the original table. The hotel occasionally stages an original musical production, ''The Talk of the Town'', in the Oak Room. Its latest production started September 11, 2007 and ran through the end of the year.

A film about the members, '' The Ten-Year Lunch'' (1987), won the

Algonquin Round Table historical site

History notes and news since 1999

Algonquin Round Table

at PBS's American Masters * {{cite web , url= http://archives.nypl.org/the/22110 , title= Aviva Slesin collection of research and production materials for the ten-year lunch: the wit and legend of the Algonquin Round Table (1920s—1988) , work= Billy Rose Theatre Division , publisher=

The Algonquin Round Table was a group of

The Algonquin Round Table was a group of New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

writers, critics, actors, and wits. Gathering initially as part of a practical joke

A practical joke or prank is a trick played on people, generally causing the victim to experience embarrassment, perplexity, confusion, or discomfort.Marsh, Moira. 2015. ''Practically Joking''. Logan: Utah State University Press. The perpetrat ...

, members of "The Vicious Circle", as they dubbed themselves, met for lunch each day at the Algonquin Hotel from 1919 until roughly 1929. At these luncheons they engaged in wisecracks, wordplay, and witticisms that, through the newspaper columns of Round Table members, were disseminated across the country.

Daily association with each other, both at the luncheons and outside of them, inspired members of the Circle to collaborate creatively. The entire group worked together successfully only once, however, to create a revue

A revue is a type of multi-act popular theatre, theatrical entertainment that combines music, dance, and sketch comedy, sketches. The revue has its roots in 19th century popular entertainment and melodrama but grew into a substantial cultural pre ...

called ''No Sirree!'' which helped launch a Hollywood career for Round Tabler Robert Benchley.

In its ten years of association, the Round Table and a number of its members acquired national reputations, both for their contributions to literature and for their sparkling wit. Although some of their contemporaries, and later in life even some of its members, disparaged the group, its reputation has endured long after its dissolution.

Origin

The group that would become the Round Table began meeting in June 1919 as the result of a practical joke carried out by theatrical press agent John Peter Toohey. Toohey, annoyed at ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' drama critic Alexander Woollcott for refusing to plug one of Toohey's clients (Eugene O'Neill

Eugene Gladstone O'Neill (October 16, 1888 – November 27, 1953) was an American playwright. His poetically titled plays were among the first to introduce into the U.S. the drama techniques of Realism (theatre), realism, earlier associated with ...

) in his column, organized a luncheon supposedly to welcome Woollcott back from World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, where he had been a correspondent for '' Stars and Stripes''. Instead, Toohey used the occasion to poke fun at Woollcott on a number of fronts. Woollcott's enjoyment of the joke and the success of the event prompted Toohey to suggest that the group in attendance meet at the Algonquin each day for lunch.

The group first gathered in the Algonquin's Pergola Room (later called the Oak Room) at a long rectangular table. As they increased in number, Algonquin manager Frank Case moved them to the Rose Room and a round table. Initially the group called itself "The Board" and the luncheons "Board meetings". After being assigned a waiter named Luigi, the group re-christened itself "Luigi Board". Finally, they became "The Vicious Circle" although "The Round Table" gained wide currency after a caricature

A caricature is a rendered image showing the features of its subject in a simplified or exaggerated way through sketching, pencil strokes, or other artistic drawings (compare to: cartoon). Caricatures can be either insulting or complimentary, ...

by cartoonist Edmund Duffy of the ''Brooklyn Eagle

The ''Brooklyn Eagle'' (originally joint name ''The Brooklyn Eagle'' and ''Kings County Democrat'', later ''The Brooklyn Daily Eagle'' before shortening title further to ''Brooklyn Eagle'') was an afternoon daily newspaper published in the city ...

'' portrayed the group sitting at a round table and wearing armor.

Membership

Charter members of the Round Table included: *Franklin Pierce Adams

Franklin Pierce Adams (November 15, 1881 – March 23, 1960) was an American columnist known as Franklin P. Adams and by his initials F.P.A. Famed for his wit, he is best known for his newspaper column, "The Conning Tower", and his appearances a ...

, columnist

* Robert Benchley, humorist and actor

* Heywood Broun, columnist and sportswriter (married to Ruth Hale)

* Marc Connelly, playwright

* Ruth Hale, freelance writer who worked for women's rights

* George S. Kaufman, playwright and director

* Dorothy Parker, critic, poet, short-story writer, and screenwriter

* Brock Pemberton, Broadway producer

* Murdock Pemberton, Broadway publicist, writer

* Harold Ross, ''The New Yorker

''The New Yorker'' is an American magazine featuring journalism, commentary, criticism, essays, fiction, satire, cartoons, and poetry. It was founded on February 21, 1925, by Harold Ross and his wife Jane Grant, a reporter for ''The New York T ...

'' editor

* Robert E. Sherwood, author and playwright

* John Peter Toohey, Broadway publicist

* Alexander Woollcott, critic and journalist

Membership was not official or fixed. Many others moved in and out of the Circle. Some of these included:

* Tallulah Bankhead

Tallulah Brockman Bankhead (January 31, 1902 – December 12, 1968) was an American actress. Primarily an actress of the stage, Bankhead also appeared in several films including an award-winning performance in Alfred Hitchcock's ''Lifeboat (194 ...

, actress

* Norman Bel Geddes

Norman Bel Geddes (born Norman Melancton Geddes; April 27, 1893 – May 8, 1958) was an American theatrical and industrial designer, described in 2012 by the New York Times as "a brilliant craftsman and draftsman, a master of style, the 20t ...

, stage and industrial designer

* Noël Coward

Sir Noël Peirce Coward (16 December 189926 March 1973) was an English playwright, composer, director, actor, and singer, known for his wit, flamboyance, and what ''Time (magazine), Time'' called "a sense of personal style, a combination of c ...

, playwright

* Blyth Daly, actress

* Edna Ferber

Edna Ferber (August 15, 1885 – April 16, 1968) was an American novelist, short story writer and playwright. Her novels include the Pulitzer Prize-winning '' So Big'' (1924), '' Show Boat'' (1926; made into the celebrated 1927 musical), '' Cima ...

, author and playwright

* Eva Le Gallienne, actress

* Stephen Courtleigh Broadway, radio and film actor

* Margalo Gillmore, actress

* Jane Grant, journalist and feminist (married to Harold Ross)

* Beatrice Kaufman, editor and playwright (married to George S. Kaufman)

* Margaret Leech, writer and historian

* Herman J. Mankiewicz, screenwriter

* Harpo Marx, comedian and film star

* Neysa McMein, magazine illustrator

* Alice Duer Miller, writer

* Katherine Sproehnle, writer

* Laurence Stallings, writer

* Donald Ogden Stewart, playwright and screenwriter

* Frank Sullivan, journalist and humorist

* Deems Taylor

Joseph Deems Taylor (December 22, 1885 – July 3, 1966) was an American composer, radio commentator, music critic, and author. Nat Benchley, co-editor of ''The Lost Algonquin Roundtable'', referred to him as "the dean of American music." He was e ...

, composer

* Estelle Winwood, actress and comedian

* Peggy Wood, actress

Activities

In addition to the daily luncheons, members of the Round Table worked and associated with each other almost constantly. The group was devoted to games, includingcribbage

Cribbage, or crib, is a card game, traditionally for two players, that involves playing and grouping cards in combinations which gain points. It can be adapted for three or four players.

Cribbage has several distinctive features: the cribbage ...

and poker

Poker is a family of Card game#Comparing games, comparing card games in which Card player, players betting (poker), wager over which poker hand, hand is best according to that specific game's rules. It is played worldwide, with varying rules i ...

. The group had its own poker club, the Thanatopsis Literary and Inside Straight Club, which met at the hotel on Saturday nights. Regulars at the game included Kaufman, Adams, Broun, Ross and Woollcott, with non-Round Tablers Herbert Bayard Swope, silk merchant Paul Hyde Bonner, baking heir Raoul Fleischmann, actor Harpo Marx, and writer Ring Lardner sometimes sitting in. The group also played charades

Charades (, ). is a parlor game, parlor or party game, party word game, word guessing game. Originally, the game was a dramatic form of literary charades: a single person would act out each syllable of a word or phrase in order, followed by the wh ...

(which they called simply "The Game") and the "I can give you a sentence" game, which spawned Dorothy Parker's memorable sentence using the word ''horticulture'': "You can lead a horticulture but you can't make her think."

Members often visited Neshobe Island, a private island co-owned by several "Algonks"—but governed by Woollcott as a "benevolent tyrant", as his biographer Samuel Hopkins Adams charitably put it—located on several acres in the middle of Lake Bomoseen in Vermont

Vermont () is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Massachusetts to the south, New Hampshire to the east, New York (state), New York to the west, and the Provinces and territories of Ca ...

. There they would engage in their usual array of games including wink murder, which they called simply "Murder", plus croquet

Croquet ( or ) is a sport which involves hitting wooden, plastic, or composite balls with a mallet through hoops (often called Wicket, "wickets" in the United States) embedded in a grass playing court.

Variations

In all forms of croquet, in ...

.

A number of Round Tablers were inveterate practical jokers, constantly pulling pranks on one another. As time went on the jokes became ever more elaborate. Harold Ross and Jane Grant once spent weeks playing a particularly memorable joke on Woollcott involving a prized portrait of himself. They had several copies made, each slightly more askew than the last, and would periodically secretly swap them out and then later comment to Woollcott "What on earth is wrong with your portrait?" until Woollcott was beside himself. Eventually they returned the original portrait.

''No Sirree!''

Given the literary and theatrical activities of the Round Table members, it was perhaps inevitable that they would write and stage their own revue. ''No Sirree!'', staged for one night only in April 30, 1922, was a take-off of a then-popular European touring revue called '' La Chauve-Souris'', directed by Nikita Balieff. ''No Sirree!'' had its genesis at the studio of Neysa McMein, which served as something of asalon

Salon may refer to:

Common meanings

* Beauty salon

A beauty salon or beauty parlor is an establishment that provides Cosmetics, cosmetic treatments for people. Other variations of this type of business include hair salons, spas, day spas, ...

for Round Tablers away from the Algonquin. Acts included: "Opening Chorus" featuring Woollcott, Toohey, Kaufman, Connelly, Adams and Benchley with violinist Jascha Heifetz providing offstage, off-key accompaniment; "He Who Gets Flapped", a musical number featuring the song "The Everlastin' Ingenue Blues" written by Dorothy Parker and performed by Robert Sherwood accompanied by "chorus girls" including Tallulah Bankhead

Tallulah Brockman Bankhead (January 31, 1902 – December 12, 1968) was an American actress. Primarily an actress of the stage, Bankhead also appeared in several films including an award-winning performance in Alfred Hitchcock's ''Lifeboat (194 ...

, Helen Hayes

Helen Hayes MacArthur (; October 10, 1900 – March 17, 1993) was an American actress. Often referred to as the "First Lady of American Theatre", she was the second person and first woman to win EGOT, the EGOT (an Emmy, a Grammy, an Oscar, and ...

, Ruth Gillmore, Lenore Ulric and Mary Brandon; "Zowie, or the Curse of an Akins Heart"; "The Greasy Hag, an O'Neill Play in One Act" with Kaufman, Connelly and Woollcott; and "Mr. Whim Passes By—An A. A. Milne Play."

The only item of note to emerge from ''No Sirree!'' was Robert Benchley's contribution, '' The Treasurer's Report''. Benchley's disjointed parody so delighted those in attendance that Irving Berlin

Irving Berlin (born Israel Isidore Beilin; May 11, 1888 – September 22, 1989) was a Russian-born American composer and songwriter. His music forms a large part of the Great American Songbook. Berlin received numerous honors including an Acade ...

hired Benchley in 1923 to deliver the ''Report'' as part of Berlin's '' Music Box Revue'' for $500 a week. In 1928, ''Report'' was later made into a short sound film

A sound film is a Film, motion picture with synchronization, synchronized sound, or sound technologically coupled to image, as opposed to a silent film. The first known public exhibition of projected sound films took place in Paris in 1900, bu ...

in the Fox Movietone sound-on-film system by Fox Film Corporation

The Fox Film Corporation (also known as Fox Studios) was an American independent company that produced motion pictures and was formed in 1914 by the theater "chain" pioneer William Fox (producer), William Fox. It was the corporate successor to ...

. The film marked the beginning of a second career for Benchley in Hollywood.

With the success of ''No Sirree!'' the Round Tablers hoped to duplicate it with an "official" Vicious Circle production open to the public with material performed by professional actors. Kaufman and Connelly funded the revue, named ''The Forty-niners''. The revue opened in November 1922 and was a failure, running for just 15 performances.

Decline

As members of the Round Table moved into ventures outside New York City, inevitably the group drifted apart. By the early 1930s the Vicious Circle was broken. Edna Ferber said she realized it when she arrived at the Rose Room for lunch one day in 1932 and found the group's table occupied by a family from Kansas. Frank Case was asked what happened to the group. He shrugged and replied, "What became of the reservoir at Fifth Avenue and Forty-Second Street? These things do not last forever." Some members of the group remained friends after its dissolution. Parker and Benchley in particular remained close up until his death in 1945, although her political leanings did strain their relationship. Others, as the group itself would come to understand when it gathered following Woollcott's death in 1943, simply realized that they had nothing to say to one another.Public response and legacy

Because a number of the members of the Round Table had regular newspaper columns, the activities and quips of various Round Table members were reported in the national press. This brought Round Tablers widely into the public consciousness as renowned wits. Not all of their contemporaries were fans of the group. Their critics accused them of '' logrolling'', or exchanging favorable plugs of one another's works, and of rehearsing their witticisms in advance. James Thurber (who lived in the hotel) was a detractor of the group, accusing them of being too consumed by their elaborate practical jokes. H. L. Mencken, who was much admired by many in the Circle, was also a critic, commenting to fellow writer Anita Loos that "their ideals were those of avaudeville

Vaudeville (; ) is a theatrical genre of variety entertainment which began in France in the middle of the 19th century. A ''vaudeville'' was originally a comedy without psychological or moral intentions, based on a comical situation: a drama ...

actor, one who is extremely 'in the know' and inordinately trashy".

The group showed up in the 1923 best-seller '' Black Oxen'' by Gertrude Atherton. She sarcastically described a group she called "the Sophisticates":

Groucho Marx

Julius Henry "Groucho" Marx (; October 2, 1890 – August 19, 1977) was an American comedian, actor, writer, and singer who performed in films and vaudeville on television, radio, and the stage. He is considered one of America's greatest comed ...

, brother of Round Table associate Harpo, was never comfortable amidst the viciousness of the Vicious Circle. Therein he remarked "The price of admission is a serpent's tongue and a half-concealed stiletto." Even some members of the Round Table disparaged it later in life. Dorothy Parker in particular criticized the group.

Despite Parker's bleak assessment and while it is true that some members of the Round Table are perhaps now " famous for being famous" instead of for their literary output, Round Table members and associates contributed to the literary landscape, including Pulitzer Prize

The Pulitzer Prizes () are 23 annual awards given by Columbia University in New York City for achievements in the United States in "journalism, arts and letters". They were established in 1917 by the will of Joseph Pulitzer, who had made his fo ...

-winning work by Circle members Kaufman, Connelly and Sherwood (who won four) and by associate Ferber and the legacy of Ross's '' New Yorker''. Others made lasting contributions to the realms of stage and screenTallulah Bankhead

Tallulah Brockman Bankhead (January 31, 1902 – December 12, 1968) was an American actress. Primarily an actress of the stage, Bankhead also appeared in several films including an award-winning performance in Alfred Hitchcock's ''Lifeboat (194 ...

and Eva Le Gallienne became Broadway greats and the films of Harpo and Benchley remain popular; and Parker has remained renowned for her short stories and literary reviews.

The Algonquin Round Table, as well as the number of other literary and theatrical greats who lodged there, helped earn the Algonquin Hotel its status as a New York City Historic Landmark. The hotel was so designated in 1987. In 1996 the hotel was designated a national literary landmark by the Friends of Libraries USA based on the contributions of "The Round Table Wits". The organization's bronze plaque is attached to the front of the hotel.

Although the Rose Room was removed from the Algonquin in a 1998 remodel, the hotel paid tribute to the group by commissioning and hanging the painting ''A Vicious Circle'' by Natalie Ascencios, depicting the Round Table and also created a replica of the original table. The hotel occasionally stages an original musical production, ''The Talk of the Town'', in the Oak Room. Its latest production started September 11, 2007 and ran through the end of the year.

A film about the members, '' The Ten-Year Lunch'' (1987), won the

The Algonquin Round Table, as well as the number of other literary and theatrical greats who lodged there, helped earn the Algonquin Hotel its status as a New York City Historic Landmark. The hotel was so designated in 1987. In 1996 the hotel was designated a national literary landmark by the Friends of Libraries USA based on the contributions of "The Round Table Wits". The organization's bronze plaque is attached to the front of the hotel.

Although the Rose Room was removed from the Algonquin in a 1998 remodel, the hotel paid tribute to the group by commissioning and hanging the painting ''A Vicious Circle'' by Natalie Ascencios, depicting the Round Table and also created a replica of the original table. The hotel occasionally stages an original musical production, ''The Talk of the Town'', in the Oak Room. Its latest production started September 11, 2007 and ran through the end of the year.

A film about the members, '' The Ten-Year Lunch'' (1987), won the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature

The Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature Film is an award for documentary films. In 1941, the first awards for feature-length documentaries were bestowed as Academy Honorary Award, Special Awards to ''Kukan'' and ''Target for Tonight''. The ...

.

The dramatic film '' Mrs. Parker and the Vicious Circle'' (1994) recounts the Round Table from the perspective of Dorothy Parker.

See also

*References

External links

Algonquin Round Table historical site

History notes and news since 1999

Algonquin Round Table

at PBS's American Masters * {{cite web , url= http://archives.nypl.org/the/22110 , title= Aviva Slesin collection of research and production materials for the ten-year lunch: the wit and legend of the Algonquin Round Table (1920s—1988) , work= Billy Rose Theatre Division , publisher=

New York Public Library for the Performing Arts

The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Dorothy and Lewis B. Cullman Center, is located at 40 Lincoln Center Plaza, in the Lincoln Center complex on the Upper West Side in Manhattan, New York City. Situated between the Metropolitan O ...

American literary movements

American humorists

Culture of Manhattan

Literary circles

20th-century American literature

Writing circles