Affective forecasting on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Affective forecasting, also known as hedonic forecasting or the hedonic forecasting mechanism, is the prediction of one's affect (

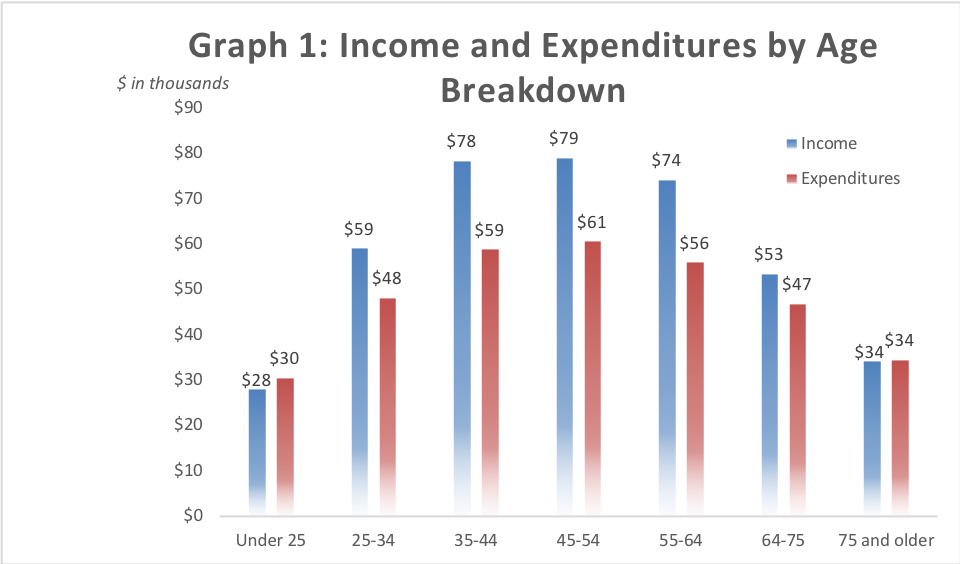

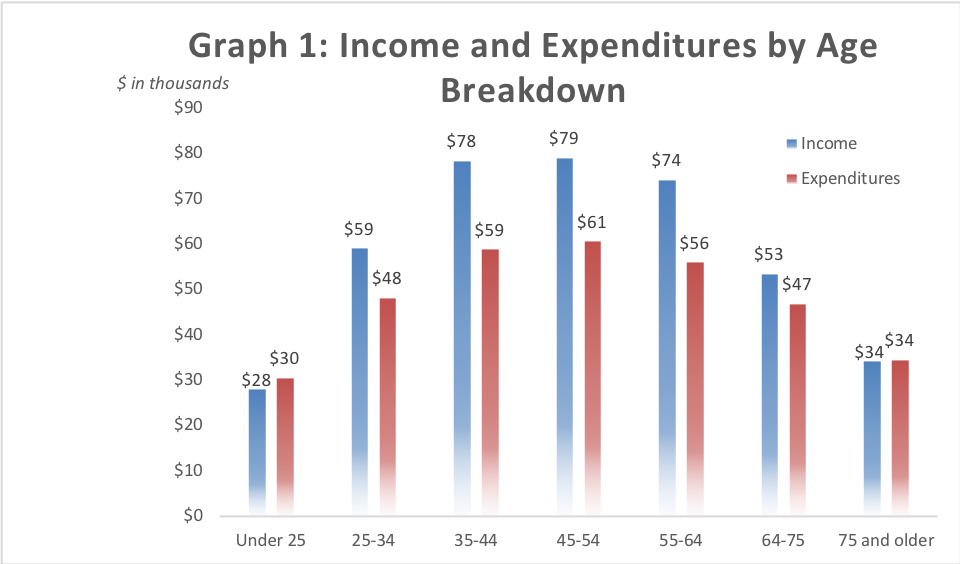

Projection bias influences the life cycle of consumption. The immediate utility obtained from consuming particular goods exceeds the utility of future consumption. Consequently, projection bias causes "a person to (plan to) consume too much early in life and too little late in life relative to what would be optimal". Graph 1 displays decreasing expenditures as a percentage of total income from 20 to 54. The period following where income begins to decline can be explained by retirement. According to Loewenstein's recommendation, a more optimal expenditure and income distribution is displayed in Graph 2. Here, income is left the same as in Graph 1, but expenditures are recalculated by taking the average percentage of expenditures in terms of income from ages 25 to 54 (77.7%) and multiplying such by income to arrive at a theoretical expenditure. The calculation is only applied to this age group because of unpredictable income before 25 and after 54 due to school and retirement.

Projection bias influences the life cycle of consumption. The immediate utility obtained from consuming particular goods exceeds the utility of future consumption. Consequently, projection bias causes "a person to (plan to) consume too much early in life and too little late in life relative to what would be optimal". Graph 1 displays decreasing expenditures as a percentage of total income from 20 to 54. The period following where income begins to decline can be explained by retirement. According to Loewenstein's recommendation, a more optimal expenditure and income distribution is displayed in Graph 2. Here, income is left the same as in Graph 1, but expenditures are recalculated by taking the average percentage of expenditures in terms of income from ages 25 to 54 (77.7%) and multiplying such by income to arrive at a theoretical expenditure. The calculation is only applied to this age group because of unpredictable income before 25 and after 54 due to school and retirement.

"Why are we happy?"

(video lecture), TED.com, Retrieved 2009-08-29

Psychlopedia on Affective Forecasting

* Daniel Gilbert

Affective forecasting on Psychology Today

{{Emotion-footer Psychological methodology Behavioral economics

emotion

Emotions are physical and mental states brought on by neurophysiology, neurophysiological changes, variously associated with thoughts, feelings, behavior, behavioral responses, and a degree of pleasure or suffering, displeasure. There is ...

al state) in the future. As a process that influences preferences, decisions, and behavior

Behavior (American English) or behaviour (British English) is the range of actions of Individual, individuals, organisms, systems or Artificial intelligence, artificial entities in some environment. These systems can include other systems or or ...

, affective forecasting is studied by both psychologist

A psychologist is a professional who practices psychology and studies mental states, perceptual, cognitive, emotional, and social processes and behavior. Their work often involves the experimentation, observation, and explanation, interpretatio ...

s and economists, with broad applications.

History

In '' The Theory of Moral Sentiments'' (1759), Adam Smith observed the personal challenges, and social benefits, of hedonic forecasting errors:onsider te poor man's son, whom heaven in its anger has visited with ambition, when he begins to look around him, admires the condition of the rich …. and, in order to arrive at it, he devotes himself for ever to the pursuit of wealth and greatness…. Through the whole of his life he pursues the idea of a certain artificial and elegant repose which he may never arrive at, for which he sacrifices a real tranquillity that is at all times in his power, and which, if in the extremity of old age he should at last attain…, he will find to be in no respect preferable to that humble security and contentment which he had abandoned for it. It is then, in the last dregs of life, his body wasted with toil and diseases, his mind galled and ruffled by the memory of a thousand injuries and disappointments..., that he begins at last to find that wealth and greatness are mere trinkets of frivolous utility…. etit is well that nature imposes upon us in this manner. It is this deception which rouses and keeps in continual motion the industry of mankind.In the early 1990s, Kahneman and Snell began research on hedonic forecasts, examining its impact on

decision making

In psychology, decision-making (also spelled decision making and decisionmaking) is regarded as the cognitive process resulting in the selection of a belief or a course of action among several possible alternative options. It could be either ra ...

. The term "affective forecasting" was later coined by psychologists Timothy Wilson and Daniel Gilbert. Early research tended to focus solely on measuring emotional forecasts, while subsequent studies began to examine the accuracy of forecasts, revealing that people are surprisingly poor judges of their future emotional states. For example, in predicting how events like winning the lottery might affect their happiness, people are likely to overestimate future positive feelings, ignoring the numerous other factors that might contribute to their emotional state outside of the single lottery event. Some of the cognitive biases related to systematic errors in affective forecasts are focalism, hot-cold empathy gap, and impact bias.

Applications

While affective forecasting has traditionally drawn the most attention from economists and psychologists, their findings have in turn generated interest from a variety of other fields, including happiness research, law, andhealth care

Health care, or healthcare, is the improvement or maintenance of health via the preventive healthcare, prevention, diagnosis, therapy, treatment, wikt:amelioration, amelioration or cure of disease, illness, injury, and other disability, physic ...

. Its effect on decision-making and well-being

Well-being is what is Intrinsic value (ethics), ultimately good for a person. Also called "welfare" and "quality of life", it is a measure of how well life is going for someone. It is a central goal of many individual and societal endeavors.

...

is of particular concern to policy-makers and analysts in these fields, although it also has applications in ethics

Ethics is the philosophy, philosophical study of Morality, moral phenomena. Also called moral philosophy, it investigates Normativity, normative questions about what people ought to do or which behavior is morally right. Its main branches inclu ...

. For example, one's tendency to underestimate one's ability to adapt to life-changing events has led to legal theorists questioning the assumptions behind tort

A tort is a civil wrong, other than breach of contract, that causes a claimant to suffer loss or harm, resulting in legal liability for the person who commits the tortious act. Tort law can be contrasted with criminal law, which deals with cri ...

damage compensation. Behavioral economists have incorporated discrepancies between forecasts and actual emotional outcomes into their models of different types of utility and welfare. This discrepancy also concerns healthcare analysts, in that many important health

Health has a variety of definitions, which have been used for different purposes over time. In general, it refers to physical and emotional well-being, especially that associated with normal functioning of the human body, absent of disease, p ...

decisions depend upon patients' perceptions of their future quality of life.

Overview

Affective forecasting can be divided into four components: predictions about valence (i.e. positive or negative), the specific emotions experienced, their duration, and their intensity. While errors may occur in all four components, research overwhelmingly indicates that the two areas most prone to bias, usually in the form of overestimation, are duration and intensity. Immune neglect is a form of impact bias in response to negative events, in which people fail to predict how much their recovery will be hastened by their psychological immune system. The psychological immune system is a metaphor "for that system of defenses that helps you feel better when bad things happen", according to Gilbert. On average, people are fairly accurate about predicting which emotions they will feel in response to future events. However, some studies indicate that predicting specific emotions in response to more complex social events leads to greater inaccuracy. For example, one study found that while many women who imagine encountering gender harassment predict feelings of anger, in reality, a much higher proportion report feelings of fear. Other research suggests that accuracy in affective forecasting is greater for positive affect than negative affect, suggesting an overall tendency to overreact to perceived negative events. Gilbert and Wilson posit that this is a result of the psychological immune system. While affective forecasts take place in the present moment, researchers also investigate its future outcomes. That is, they analyze forecasting as a two-step process, encompassing a current prediction as well as a future event. Breaking down the present and future stages allow researchers to measure accuracy, as well as tease out how errors occur. Gilbert and Wilson, for example, categorize errors based on which component they affect and when they enter the forecasting process. In the present phase of affective forecasting, forecasters bring to mind a mental representation of the future event and predict how they will respond emotionally to it. The future phase includes the initial emotional response to the onset of the event, as well as subsequent emotional outcomes, for example, the fading of the initial feeling. When errors occur throughout the forecasting process, people are vulnerable to biases. These biases disable people from accurately predicting their future emotions. Errors may arise due to extrinsic factors, such as framing effects, or intrinsic ones, such as cognitive biases or expectation effects. Because accuracy is often measured as the discrepancy between a forecaster's present prediction and the eventual outcome, researchers also study how time affects affective forecasting. For example, the tendency for people to represent distant events differently from close events is captured in the construal level theory. The finding that people are generally inaccurate affective forecasters has been most obviously incorporated into conceptualizations of happiness and its successful pursuit, as well as decision making across disciplines. Findings in affective forecasts have stimulated philosophical and ethical debates, for example, on how to define welfare. On an applied level, findings have informed various approaches to healthcare policy, tort law,consumer

A consumer is a person or a group who intends to order, or use purchased goods, products, or services primarily for personal, social, family, household and similar needs, who is not directly related to entrepreneurial or business activities. ...

decision making, and measuring utility (see below sections on economics

Economics () is a behavioral science that studies the Production (economics), production, distribution (economics), distribution, and Consumption (economics), consumption of goods and services.

Economics focuses on the behaviour and interac ...

, law, and health

Health has a variety of definitions, which have been used for different purposes over time. In general, it refers to physical and emotional well-being, especially that associated with normal functioning of the human body, absent of disease, p ...

).

Newer and conflicting evidence suggests that intensity bias in affective forecasting may not be as strong as previous research indicates. Five studies, including a meta-analysis, recover evidence that overestimation in affective forecasting is partly due to the methodology of past research. Their results indicate that some participants misinterpreted specific questions in affective forecasting testing. For example, one study found that undergraduate students tended to overestimate experienced happiness levels when participants were asked how they were feeling in ''general'' with and without reference to the election, compared to when participants were asked how they were feeling ''specifically'' in reference to the election. Findings indicated that 75%-81% of participants who were asked general questions misinterpreted them. After clarification of tasks, participants were able to more accurately predict the intensity of their emotions

Major sources of errors

Because forecasting errors commonly arise from literature on cognitive processes, many affective forecasting errors derive from and are often framed as cognitive biases, some of which are closely related or overlapping constructs (e.g. projection bias and empathy gap). Below is a list of commonly cited cognitive processes that contribute to forecasting errors.Major sources of error in emotion

Impact bias

One of the most common sources of error in affective forecasting across various populations and situations is impact bias, the tendency to overestimate the emotional impact of a future event, whether in terms of intensity or duration. The tendencies to overestimate intensity and duration are both robust and reliable errors found in affective forecasting. One study documenting impact bias examined college students participating in a housing lottery. These students predicted how happy or unhappy they would be one year after being assigned to either a desirable or an undesirable dormitory. These college students predicted that the lottery outcomes would lead to meaningful differences in their own level of happiness, but follow-up questionnaires revealed that students assigned to desirable or undesirable dormitories reported nearly the same levels of happiness. Thus, differences in forecasts overestimated the impact of the housing assignment on future happiness. Some studies specifically address "durability bias," the tendency to overestimate the length of time future emotional responses will last. Even if people accurately estimate the intensity of their future emotions, they may not be able to estimate their duration. Durability bias is generally stronger in reaction to negative events. This is important because people tend to work toward events they believe will cause lasting happiness, and according to durability bias, people might be working toward the wrong things. Similar to impact bias, durability bias causes a person to overemphasize where the root cause of their happiness lies. Impact bias is a broad term and covers a multitude of more specific errors. Proposed causes of impact bias include mechanisms like immune neglect, focalism, and misconstruals. The pervasiveness of impact bias in affective forecasts is of particular concern to healthcare specialists, in that it affects both patients' expectations of future medical events as well as patient-provider relationships. (Seehealth

Health has a variety of definitions, which have been used for different purposes over time. In general, it refers to physical and emotional well-being, especially that associated with normal functioning of the human body, absent of disease, p ...

.)

Expectation effects

Previously formed expectations can alter emotional responses to the event itself, motivating forecasters to confirm or debunk their initial forecasts. In this way, the self-fulfilling prophecy can lead to the perception that forecasters have made accurate predictions. Inaccurate forecasts can also become amplified by expectation effects. For example, a forecaster who expects a movie to be enjoyable will, upon finding it dull, like it significantly less than a forecaster who had no expectations.Sense-making processes

Major life events can have a huge impact on people's emotions for a very long time but the intensity of that emotion tends to decrease with time, a phenomenon known as ''emotional evanescence''. When making forecasts, forecasters often overlook this phenomenon. Psychologists have suggested that emotion does not decay over time predictably like radioactive isotopes but that the mediating factors are more complex. People have psychological processes that help dampen emotions. Psychologists have proposed that surprising, unexpected, or unlikely events cause more intense emotional reactions. Research suggests that people are unhappy with randomness and chaos and that they automatically think of ways to make sense of an event when it is surprising or unexpected. This sense-making helps individuals recover from negative events more quickly than they would have expected. This is related to immune neglect in that when these unwanted acts of randomness occur people become upset and try to find meaning or ways to cope with the event. The way that people try to make sense of the situation can be considered a coping strategy made by the body. This idea differs from immune neglect due to the fact that this is more of a momentary idea. Immune neglect tries to cope with the event before it even happens. One study documents how sense-making processes decrease emotional reactions. The study found that a small gift produced greater emotional reactions when it was not accompanied by a reason than when it was, arguably because the reason facilitated the sense-making process, dulling the emotional impact of the gift. Researchers have summarized that pleasant feelings are prolonged after a positive situation if people are uncertain about the situation. People fail to anticipate that they will make sense of events in a way that will diminish the intensity of the emotional reaction. This error is known as ''ordinization neglect''. For example, ("I will be ecstatic for many years if my boss agrees to give me a raise") an employee might believe, especially if the employee believes the probability of a raise was unlikely. Immediately after having the request approved, the employee may be thrilled but with time the employees make sense of the situation (e.g., "I am a very hard worker and my boss must have noticed this") thus dampening the emotional reaction.Immune neglect

Gilbert et al. originally coined the term immune neglect (or ) to describe a function of the psychological immune system, which is the set of processes that restore positive emotions after the experience of negative emotions. Immune neglect is people's unawareness of their tendency to adapt to and cope with negative events. Unconsciously the body will identify a stressful event and try to cope with the event or try to avoid it. Bolger & Zuckerman found that coping strategies vary between individuals and are influenced by their personalities. They assumed that since people generally do not take their coping strategies into account when they predict future events, that people with better coping strategies should have a bigger impact bias or a greater difference between their predicted and actual outcome. For example, asking someone who is afraid of clowns how going to a circus would feel may result in an overestimation of fear because the anticipation of such fear causes the body to begin coping with the negative event. Hoerger et al. examined this further by studying college students' emotions toward football games. They found that students who generally coped with their emotions instead of avoiding them would have a greater impact bias when predicting how they'd feel if their team lost the game. They found that those with better coping strategies recovered more quickly. Since the participants did not think about their coping strategies when making predictions, those who actually coped had a greater impact bias. Those who avoided their emotions, felt very closely to what they predicted they would. In other words, students who were able to deal with their emotions were able to recover from their feelings. The students were unaware that their body was actually coping with the stress and this process made them feel better than not dealing with the stress. Hoerger ran another study on immune neglect after this, which studied both daters' and non-daters' forecasts about Valentine's Day, and how they would feel in the days that followed. Hoerger found that different coping strategies would cause people to have different emotions in the days following Valentine's Day, but participants' predicted emotions would all be similar. This shows that most people do not realize the impact that coping can have on their feelings following an emotional event. He also found that not only did immune neglect create a bias for negative events, but also for positive ones. This shows that people continually make inaccurate forecasts because they do not take into account their ability to cope and overcome emotional events. Hoerger proposed that coping styles and cognitive processes are associated with actual emotional reactions to life events. A variant of immune neglect also proposed by Gilbert and Wilson is the region-beta paradox, where recovery from more intense suffering is faster than recovery from less intense experiences because of the engagement of coping systems. This complicates forecasting, leading to errors. Contrarily, accurate affective forecasting can also promote the region-beta paradox. For example, Cameron and Payne conducted a series of studies in order to investigate the relationship between affective forecasting and the collapse of compassion phenomenon, which refers to the tendency for people's compassion to decrease as the number of people in need of help increases. Participants in their experiments read about either 1 or a group of 8 children from Darfur. These researchers found that people who are skilled at regulating their emotions tended to experience less compassion in response to stories about 8 children from Darfur compared to stories about only 1 child. These participants appeared to collapse their compassion by correctly forecasting their future affective states and proactively avoiding the increased negative emotions resulting from the story. In order to further establish the causal role of proactive emotional regulation in this phenomenon, participants in another study read the same materials and were encouraged to either reduce or experience their emotions. Participants instructed to reduce their emotions reported feeling less upset for 8 children than for 1, presumably because of the increased emotional burden and effort required for the former (an example of the region-beta paradox). These studies suggest that in some cases accurate affective forecasting can actually promote unwanted outcomes such as the collapse of compassion phenomenon by way of the region-beta paradox.Positive vs negative affect

Research suggests that the accuracy of affective forecasting for positive and negative emotions is based on the distance in time of the forecast. Finkenauer, Gallucci, van Dijk, and Pollman discovered that people show greater forecasting accuracy for positive than negative affect when the event or trigger being forecast is more distant in time. Contrarily, people exhibit greater affective forecasting accuracy for negative affect when the event/trigger is closer in time. The accuracy of an affective forecast is also related to how well a person predicts the intensity of his or her emotions. In regard to forecasting both positive and negative emotions, Levine, Kaplan, Lench, and Safer have recently shown that people can in fact predict the intensity of their feelings about events with a high degree of accuracy. This finding is contrary to much of the affective forecasting literature currently published, which the authors suggest is due to a procedural artifact in how these studies were conducted. Another important affective forecasting bias is fading affect bias, in which the emotions associated with unpleasant memories fade more quickly than the emotion associated with positive events.Major sources of error in cognition

Focalism

Focalism (or the " focusing illusion") occurs when people focus too much on certain details of an event, ignoring other factors. Research suggests that people have a tendency to exaggerate aspects of life when focusing their attention on it. A well-known example originates from a paper by Kahneman and Schkade, who coined the term "focusing illusion" in 1998. They found that although people tended to believe that someone from the Midwest would be more satisfied if they lived in California, results showed equal levels oflife satisfaction

Life satisfaction is an evaluation of a person's quality of life. It is assessed in terms of mood, relationship satisfaction, achieved goals, self-concepts, and the self-perceived ability to cope with life. Life satisfaction involves a favorabl ...

in residents of both regions. In this case, concentrating on the easily observed difference in weather bore more weight in predicting satisfaction than other factors. There are many other factors that could have contributed to the desire to move to the Midwest, but the focal point for their decisions was weather. Various studies have attempted to "defocus" participants, meaning instead of focusing on that one factor, they tried to make the participants think of other factors or look at the situation through a different lens. There were mixed results dependent upon the methods used. One successful study asked people to imagine how happy a winner of the lottery and a recently diagnosed HIV patient would be. The researchers were able to reduce the amount of focalism by exposing participants to detailed and mundane descriptions of each person's life, meaning that the more information the participants had on the lottery winner and the HIV patient the less they were able to only focus on few factors, these participants subsequently estimated similar levels of happiness for the HIV patient as well as the lottery-winner. As for the control participants, they made unrealistically disparate predictions of happiness. This could be due to the fact that the more information that is available, the less likely it is one will be able to ignore contributory factors.

Time discounting

Time discounting (or time preference) is the tendency to weigh present events over future events. Immediate gratification is preferred to delayed gratification, especially over longer periods of time and with younger children or adolescents. For example, a child may prefer one piece of candy now (1 candy/0 seconds=infinity candies/second) instead of five pieces of candy in four months (5 candies/10540800 seconds≈0.00000047candies/second). The bigger the candies/second, the more people like it. This pattern is sometimes referred to as hyperbolic discounting or "present bias" because people's judgements are biased toward present events. Economists often cite time discounting as a source of mispredictions of future utility.Memory

Affective forecasters often rely on memories of past events. When people report memories of past events they may leave out important details, change things that occurred, and even add things that have not happened. This suggests the mind constructs memories based on what actually happened, and other factors including the person's knowledge, experiences, and existing schemas. Using highly available, but unrepresentative memories, increases the impact bias. Baseball fans, for example, tend to use the best game they can remember as the basis for their affective forecast of the game they are about to see. Commuters are similarly likely to base their forecasts of how unpleasant it would feel to miss a train on their memory of the worst time they missed the train Various studies indicate that retroactive assessments of past experiences are prone to various errors, such as duration neglect or ''decay bias''. People tend to overemphasize the peaks and ends of their experiences when assessing them ( peak/end bias), instead of analyzing the event as a whole. For example, in recalling painful experiences, people place greater emphasis on the most discomforting moments as well as the end of the event, as opposed to taking into account the overall duration. Retroactive reports often conflict with present-moment reports of events, further pointing to contradictions between the actualemotion

Emotions are physical and mental states brought on by neurophysiology, neurophysiological changes, variously associated with thoughts, feelings, behavior, behavioral responses, and a degree of pleasure or suffering, displeasure. There is ...

s experienced during an event and the memory of them. In addition to producing errors in forecasts about the future, this discrepancy has incited economists to redefine different types of utility and happiness (see the section on economics

Economics () is a behavioral science that studies the Production (economics), production, distribution (economics), distribution, and Consumption (economics), consumption of goods and services.

Economics focuses on the behaviour and interac ...

).

Another problem that can arise with affective forecasting is that people tend to remember their past predictions inaccurately. Meyvis, Ratner, and Levav predicted that people forget how they predicted an experience would be beforehand, and thought their predictions were the same as their actual emotions. Because of this, people do not realize that they made a mistake in their predictions, and will then continue to inaccurately forecast similar situations in the future. Meyvis et al. ran five studies to test whether or not this is true. They found in all of their studies, when people were asked to recall their previous predictions they instead write how they currently feel about the situation. This shows that they do not remember how they thought they would feel, and makes it impossible for them to learn from this event for future experiences.

Misconstruals

When predicting future emotional states people must first construct a good representation of the event. If people have a lot of experience with the event then they can easily picture the event. When people do not have much experience with the event they need to create a representation of what the event likely contains. For example, if people were asked how they would feel if they lost one hundred dollars in a bet, gamblers are more likely to easily construct an accurate representation of the event. "Construal level theory" theorizes that distant events are conceptualized more abstractly than immediate ones. Thus, psychologists suggest that a lack of concrete details prompts forecasters to rely on more general or idealized representations of events, which subsequently leads to simplistic and inaccurate predictions. For example, when asked to imagine what a 'good day' would be like for them in the near future, people often describe both positive and negative events. When asked to imagine what a 'good day' would be like for them in a year, however, people resort to more uniformly positive descriptions. Gilbert and Wilson call bringing to mind a flawed representation of a forecasted event the ''misconstrual problem''. Framing effects, environmental context, and heuristics (such as schemas) can all affect how a forecaster conceptualizes a future event. For example, the way options are framed affects how they are represented: when asked to forecast future levels of happiness based on pictures of dorms they may be assigned to, college students use physical features of the actual buildings to predict their emotions. In this case, the framing of options highlighted visual aspects of future outcomes, which overshadowed more relevant factors to happiness, such as having a friendly roommate.Projection bias

=Overview

= Projection bias is the tendency to falsely project current preferences onto a future event. When people are trying to estimate their emotional state in the future they attempt to give an unbiased estimate. However, people's assessments are contaminated by their current emotional state. Thus, it may be difficult for them to predict their emotional state in the future, an occurrence known as ''mental contamination''. For example, if a college student was currently in a negative mood because he just found out he failed a test, and if the college student forecasted how much he would enjoy a party two weeks later, his current negative mood may influence his forecast. In order to make an accurate forecast the student would need to be aware that his forecast is biased due to mental contamination, be motivated to correct the bias, and be able to correct the bias in the right direction and magnitude. Projection bias can arise from empathy gaps (or hot/cold empathy gaps), which occur when the present and future phases of affective forecasting are characterized by different states of physiological arousal, which the forecaster fails to take into account. For example, forecasters in a state of hunger are likely to overestimate how much they will want to eat later, overlooking the effect of their hunger on future preferences. As with projection bias, economists use the visceral motivations that produce empathy gaps to help explain impulsive or self-destructive behaviors, such as smoking. An important affective forecasting bias related to projection bias is personality neglect. Personality neglect refers to a person's tendency to overlook their personality when making decisions about their future emotions. In a study conducted by Quoidbach and Dunn, students' predictions of their feelings about future exam scores were used to measure affective forecasting errors related to personality. They found that college students who predicted their future emotions about their exam scores were unable to relate these emotions to their own dispositional happiness. To further investigate personality neglect, Quoidbach and Dunn studied happiness in relation to neuroticism. People predicted their future feelings about the outcome of the 2008 US presidential election betweenBarack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II (born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who was the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, he was the first African American president in American history. O ...

and John McCain

John Sidney McCain III (August 29, 1936 – August 25, 2018) was an American statesman and United States Navy, naval officer who represented the Arizona, state of Arizona in United States Congress, Congress for over 35 years, first as ...

. Neuroticism was correlated with impact bias, which is the overestimation of the length and intensity of emotions. People who rated themselves as higher in neuroticism overestimated their happiness in response to the election of their preferred candidate, suggesting that they failed to relate their dispositional happiness to their future emotional state.

The term "projection bias" was first introduced in the 2003 paper "Projection Bias in Predicting Future Utility" by Loewenstein, O'Donoghue and Rabin.

=Market applications of projection bias

= The novelty of new products oftentimes overexcites consumers and results in the negative consumption externality of impulse buying. To counteract such, George Loewenstein recommends offering "cooling off" Loewenstein, George, Exotic Preferences: Behavioral Economics and Human Motivation, p. 366, Oxford University Press, New York periods for consumers. During such, they would have a few days to reflect on their purchase and appropriately develop a longer-term understanding of the utility they receive from it. This cooling-off period could also benefit the production side by diminishing the need for a salesperson to "hype" certain products. Transparency between consumers and producers would increase as "sellers will have an incentive to put buyers in a long-run average mood rather than an overenthusiastic state". By implementing Loewentstein's recommendation, firms that understand projection bias should minimize information asymmetry; such would diminish the negative consumer externality that comes from purchasing an undesirable good and relieve sellers from extraneous costs required to exaggerate the utility of their product.=Life-cycle consumption

= Projection bias influences the life cycle of consumption. The immediate utility obtained from consuming particular goods exceeds the utility of future consumption. Consequently, projection bias causes "a person to (plan to) consume too much early in life and too little late in life relative to what would be optimal". Graph 1 displays decreasing expenditures as a percentage of total income from 20 to 54. The period following where income begins to decline can be explained by retirement. According to Loewenstein's recommendation, a more optimal expenditure and income distribution is displayed in Graph 2. Here, income is left the same as in Graph 1, but expenditures are recalculated by taking the average percentage of expenditures in terms of income from ages 25 to 54 (77.7%) and multiplying such by income to arrive at a theoretical expenditure. The calculation is only applied to this age group because of unpredictable income before 25 and after 54 due to school and retirement.

Projection bias influences the life cycle of consumption. The immediate utility obtained from consuming particular goods exceeds the utility of future consumption. Consequently, projection bias causes "a person to (plan to) consume too much early in life and too little late in life relative to what would be optimal". Graph 1 displays decreasing expenditures as a percentage of total income from 20 to 54. The period following where income begins to decline can be explained by retirement. According to Loewenstein's recommendation, a more optimal expenditure and income distribution is displayed in Graph 2. Here, income is left the same as in Graph 1, but expenditures are recalculated by taking the average percentage of expenditures in terms of income from ages 25 to 54 (77.7%) and multiplying such by income to arrive at a theoretical expenditure. The calculation is only applied to this age group because of unpredictable income before 25 and after 54 due to school and retirement.

=Food waste

= When buying food, people often wrongly project what they will want to eat in the future when they go shopping, which results infood waste

The causes of food going uneaten are numerous and occur throughout the food system, during food production, production, food processing, processing, Food distribution, distribution, Grocery store, retail and food service sales, and Social clas ...

.

Major sources of error in motivation

Motivated reasoning

Generally, affect is a potent source of motivation. People are more likely to pursue experiences and achievements that will bring them more pleasure than less pleasure. In some cases, affective forecasting errors appear to be due to forecasters' strategic use of their forecasts as a means to motivate them to obtain or avoid the forecasted experience. Students, for example, might predict they would be devastated if they failed a test as a way to motivate them to study harder for it. The role of motivated reasoning in affective forecasting has been demonstrated in studies by Morewedge and Buechel (2013). Research participants were more likely to overestimate how happy they would be if they won a prize, or achieved a goal, if they made an affective forecast while they could still influence whether or not they achieved it than if they made an affective forecast after the outcome had been determined (while still in the dark about whether they knew if they won the prize or achieved the goal).In economics

Economists share psychologists' interests in affective forecasting insomuch as it affects the closely related concepts of utility,decision making

In psychology, decision-making (also spelled decision making and decisionmaking) is regarded as the cognitive process resulting in the selection of a belief or a course of action among several possible alternative options. It could be either ra ...

, and happiness.

Utility

Research in affective forecasting errors complicates conventional interpretations of utility maximization, which presuppose that to make rational decisions, people must be able to make accurate forecasts about future experiences or utility. Whereaseconomics

Economics () is a behavioral science that studies the Production (economics), production, distribution (economics), distribution, and Consumption (economics), consumption of goods and services.

Economics focuses on the behaviour and interac ...

formerly focused largely on utility in terms of a person's preferences (decision utility), the realization that forecasts are often inaccurate suggests that measuring preferences at a time of choice

A choice is the range of different things from which a being can choose. The arrival at a choice may incorporate Motivation, motivators and Choice modelling, models.

Freedom of choice is generally cherished, whereas a severely limited or arti ...

may be an incomplete concept of utility. Thus, economists such as Daniel Kahneman, have incorporated differences between affective forecasts and later outcomes into corresponding types of utility. Whereas a current forecast reflects ''expected'' or ''predicted utility'', the actual outcome of the event reflects ''experienced utility''. Predicted utility is the "weighted average of all possible outcomes under certain circumstances." Experienced utility refers to the perceptions of pleasure and pain associated with an outcome. Kahneman and Thaler provide an example of "the hungry shopper," in which case the shopper takes pleasure in the purchase of food due to their current state of hunger. The usefulness of such purchasing is based on their current experience and their anticipated pleasure in fulfilling their hunger.

Decision making

Affective forecasting is an important component of studying humandecision making

In psychology, decision-making (also spelled decision making and decisionmaking) is regarded as the cognitive process resulting in the selection of a belief or a course of action among several possible alternative options. It could be either ra ...

. Research in affective forecasts and economic decision making include investigations of durability bias in consumers and predictions of public transit satisfaction. In relevance to the durability bias in consumers, a study was conducted by Wood and Bettman, that showed that people make decisions regarding the consumption of goods based on the predicted pleasure, and the duration of that pleasure, that the goods will bring them. Overestimation of such pleasure, and its duration, increases the likelihood that the good will be consumed. Knowledge on such an effect can aid in the formation of marketing strategies of consumer goods. Studies regarding the predictions of public transit satisfaction reveal the same bias. However, with a negative impact on consumption, due to their lack of experience with public transportation, car users predict that they will receive less satisfaction with the use of public transportation than they actually experience. This can lead them to refrain from the use of such services, due to inaccurate forecasting. Broadly, the tendencies people have to make biased forecasts deviate from rational models of decision making. Rational models of decision making presume an absence of bias, in favor of making comparisons based on all relevant and available information. Affective forecasting may cause consumers to rely on the feelings associated with consumption rather than the utility of the good itself. One application of affective forecasting research is in economic policy. The knowledge that forecasts, and therefore, decisions, are affected by biases as well as other factors (such as framing effects), can be used to design policies that maximize the utility of people's choices. This approach is not without its critics, however, as it can also be seen to justify economic paternalism.

Prospect theory describes how people make decisions. It differs from expected utility theory in that it takes into account the relativity of how people view utility and incorporates loss aversion, or the tendency to react more strongly to losses rather than gains. Some researchers suggest that loss aversion is in itself an affective forecasting error since people often overestimate the impact of future losses.

Happiness and well-being

Economic definitions of happiness are tied to concepts of welfare and utility, and researchers are often interested in how to increase levels of happiness in the population. The economy has a major influence on the aid that is provided through welfare programs because it provides funding for such programs. Many welfare programs are focused on providing assistance with the attainment of basic necessities such as food and shelter. This may be due to the fact that happiness and well-being are best derived from personal perceptions of one's ability to provide these necessities. This statement is supported by research that states after basic needs have been met, income has less of an impact on perceptions of happiness. Additionally, the availability of such welfare programs can enable those that are less fortunate to have additional discretionary income. Discretionary income can be dedicated to enjoyable experiences, such as family outings, and in turn, provides an additional dimension to their feelings and experience of happiness. Affective forecasting provides a unique challenge to answering the question regarding the best method for increasing levels of happiness, and economists are split between offering morechoice

A choice is the range of different things from which a being can choose. The arrival at a choice may incorporate Motivation, motivators and Choice modelling, models.

Freedom of choice is generally cherished, whereas a severely limited or arti ...

s to maximize happiness, versus offering experiences that contain more ''objective ''or ''experienced utility''. Experienced utility refers to how useful an experience is in its contribution to feelings of happiness and well-being. Experienced utility can refer to both material purchases and experiential purchases. Studies show that experiential purchases, such as a bag of chips, result in forecasts of higher levels of happiness than material purchases, such as the purchase of a pen. This prediction of happiness as a result of a purchase experience exemplifies affective forecasting. It is possible that an increase in choices, or means, of achieving desired levels of happiness will be predictive of increased levels of happiness. For example, if one is happy with their ability to provide themselves with both a choice of necessities and a choice of enjoyable experiences they are more likely to predict that they will be happier than if they were forced to choose between one or the other. Also, when people are able to reference multiple experiences that contribute to their feelings of happiness, more opportunities for comparison will lead to a forecast of more happiness. Under these circumstances, both the number of choices and the quantity of experienced utility have the same effect on affective forecasting, which makes it difficult to choose a side of the debate on which method is most effective in maximizing happiness.

Applying findings from affective forecasting research to happiness also raises methodological issues: should happiness measure the outcome of an experience or the satisfaction experienced as a result of the choice made based upon a forecast? For example, although professors may forecast that getting tenure would significantly increase their happiness, research suggests that in reality, happiness levels between professors who are or are not awarded tenure are insignificant. In this case happiness is measured in terms of the outcome of an experience. Affective forecasting conflicts such as this one have also influenced theories of hedonic adaptation, which compares happiness to a treadmill, in that it remains relatively stable despite forecasts.

In law

Similar to how some economists have drawn attention to how affective forecasting violates assumptions of rationality, legal theorists point out that inaccuracies in, and applications of, these forecasts have implications in law that have remained overlooked. The application of affective forecasting, and its related research, to legal theory reflects a wider effort to address how emotions affect the legal system. In addition to influencing legal discourse onemotion

Emotions are physical and mental states brought on by neurophysiology, neurophysiological changes, variously associated with thoughts, feelings, behavior, behavioral responses, and a degree of pleasure or suffering, displeasure. There is ...

s,

and welfare, Jeremy Blumenthal cites additional implications of affective forecasting in tort damages, capital sentencing and sexual harassment

Sexual harassment is a type of harassment based on the sex or gender of a victim. It can involve offensive sexist or sexual behavior, verbal or physical actions, up to bribery, coercion, and assault. Harassment may be explicit or implicit, wit ...

.

Tort damages

Jury

A jury is a sworn body of people (jurors) convened to hear evidence, make Question of fact, findings of fact, and render an impartiality, impartial verdict officially submitted to them by a court, or to set a sentence (law), penalty or Judgmen ...

awards for tort

A tort is a civil wrong, other than breach of contract, that causes a claimant to suffer loss or harm, resulting in legal liability for the person who commits the tortious act. Tort law can be contrasted with criminal law, which deals with cri ...

damages are based on compensating victims for pain, suffering, and loss of quality of life. However, findings in affective forecasting errors have prompted some to suggest that juries are overcompensating victims since their forecasts overestimate the negative impact of damages on the victims' lives. Some scholars suggest implementing jury education to attenuate potentially inaccurate predictions, drawing upon research that investigates how to decrease inaccurate affective forecasts.

Capital sentencing

During the process of capital sentencing, juries are allowed to hear victim impact statements (VIS) from the victim's family. This demonstrates affective forecasting in that its purpose is to present how the victim's family has been impacted emotionally and, or, how they expect to be impacted in the future. These statements can cause juries to overestimate the emotionalharm

Harm is a morality, moral and law, legal concept with multiple definitions. It generally functions as a synonym for evil or anything that is bad under certain moral systems. Something that causes harm is harmful, and something that does not is har ...

, causing harsh sentencing, or underestimate harm, resulting in inadequate sentencing. The time frame in which these statements are present also influences affective forecasting. By increasing the time gap between the crime itself and sentencing (the time at which victim impact statements are given), forecasts are more likely to be influenced by the error of immune neglect (See Immune neglect) Immune neglect is likely to lead to underestimation of future emotional harm, and therefore results in inadequate sentencing. As with tort damages, jury education is a proposed method for alleviating the negative effects of forecasting error.

Sexual harassment

In cases involving sexual harassment, judgements are more likely to blame the victim for their failure to react in a timely fashion or their failure to make use of services that were available to them in the event of sexual harassment. This is because prior to the actual experience of harassment, people tend to overestimate their affective reactions as well as their proactive reactions in response to sexual harassment. This exemplifies the focalism error (See Focalism) in which forecasters ignore alternative factors that may influence one's reaction, or failure to react. For example, in their study, Woodzicka and LaFrance studied women's predictions of how they would react to sexual harassment during an interview. Forecasters overestimated their affective reactions of anger, while underestimating the level of fear they would experience. They also overestimated their proactive reactions. In Study 1, participants reported that they would refuse to answer questions of a sexual nature and, or, report the question to the interviewer's supervisor. However, in Study 2, of those who had actually experienced sexual harassment during an interview, none of them displayed either proactive reaction. If juries are able to recognize such errors in forecasting, they may be able to adjust such errors. Additionally, if juries are educated on other factors that may influence the reactions of those who are victims of sexual harassment, such as intimidation, they are more likely to make more accurate forecasts, and less likely to blame victims for their own victimization.In health

Affective forecasting has implications in healthdecision making

In psychology, decision-making (also spelled decision making and decisionmaking) is regarded as the cognitive process resulting in the selection of a belief or a course of action among several possible alternative options. It could be either ra ...

and medical ethics and policy. Research in health-related affective forecasting suggests that nonpatients consistently underestimate the quality of life associated with chronic health conditions and disability. The so-called "disability paradox" states the discrepancy between self-reported levels of happiness amongst chronically ill people versus the predictions of their happiness levels by healthy people. The implications of this forecasting error in medical decision making can be severe, because judgments about future quality of life often inform health decisions. Inaccurate forecasts can lead patients, or more commonly their health care agent, to refuse life-saving treatment in cases when the treatment would involve a drastic change in lifestyle, for example, the amputation of a leg. A patient, or health care agent, who falls victim to focalism would fail to take into account all the aspects of life that would remain the same after losing a limb. Although Halpern and Arnold suggest interventions to foster awareness of forecasting errors and improve medical decision making amongst patients, the lack of direct research in the impact of biases in medical decisions provides a significant challenge.

Research also indicates that affective forecasts about future quality of life are influenced by the forecaster's current state of health

Health has a variety of definitions, which have been used for different purposes over time. In general, it refers to physical and emotional well-being, especially that associated with normal functioning of the human body, absent of disease, p ...

. Whereas healthy individuals associate future low health with low quality of life, less healthy individuals do not forecast necessarily low quality of life when imagining having poorer health. Thus, patient forecasts and preferences about their own quality of life may conflict with public notions. Because a primary goal of healthcare is maximizing quality of life, knowledge about patients' forecasts can potentially inform policy on how resources are allocated.

Some doctors suggest that research findings in affective forecasting errors merit medical paternalism. Others argue that although biases exist and should support changes in doctor-patient communication

Communication is commonly defined as the transmission of information. Its precise definition is disputed and there are disagreements about whether Intention, unintentional or failed transmissions are included and whether communication not onl ...

, they do not unilaterally diminish decision-making capacity and should not be used to endorse paternalistic policies. This debate captures the tension between medicine's emphasis on protecting the autonomy

In developmental psychology and moral, political, and bioethical philosophy, autonomy is the capacity to make an informed, uncoerced decision. Autonomous organizations or institutions are independent or self-governing. Autonomy can also be ...

of the patient

A patient is any recipient of health care services that are performed by Health professional, healthcare professionals. The patient is most often Disease, ill or Major trauma, injured and in need of therapy, treatment by a physician, nurse, op ...

and an approach that favors intervention in order to correct biases.

Improving forecasts

Individuals who recently have experienced an emotionally charged life event will display the impact bias. The individual predicts they will feel happier than they actually feel about the event. Another factor that influences overestimation is focalism which causes individuals to concentrate on the current event. Individuals often fail to realize that other events will also influence how they currently feel. Lam et al. (2005) found that the perspective that individuals take influences their susceptibility to biases when making predictions about their feelings. A perspective that overrides impact bias is mindfulness. Mindfulness is a skill that individuals can learn to help them prevent overestimating their feelings. Being mindful helps the individual understand that they may currently feel negative emotions, but the feelings are not permanent. The Five Factor Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ) can be used to measure an individual's mindfulness. The five factors of mindfulness are observing, describing, acting with awareness, non-judging of inner experience, and non-reactivity to inner experience. The two most important factors for improving forecasts are observing and acting with awareness. The observing factor assesses how often an individual attends to their sensations, emotions, and outside environment. The ability to observe allows the individual to avoid focusing on one single event, and be aware that other experiences will influence their current emotions. Acting with awareness requires assessing how individuals tend to current activities with careful consideration and concentration. Emanuel, Updegraff, Kalmbach, and Ciesla (2010) stated that the ability to act with awareness reduces the impact bias because the individual is more aware that other events co-occur with the present event. Being able to observe the current event can help individuals focus on pursuing future events that provide long-term satisfaction and fulfillment.See also

*Happiness economics

The economics of happiness or happiness economics is the theoretical, qualitative and quantitative study of happiness and quality of life, including positive and negative Affect (psychology), affects, well-being, life satisfaction and related co ...

* List of cognitive biases

* List of memory biases

* Prospect theory

* Welfare economics

Welfare economics is a field of economics that applies microeconomic techniques to evaluate the overall well-being (welfare) of a society.

The principles of welfare economics are often used to inform public economics, which focuses on the ...

References

Further reading

* * * * * ;On the projection bias * *External links

* Daniel Gilber"Why are we happy?"

(video lecture), TED.com, Retrieved 2009-08-29

Psychlopedia on Affective Forecasting

* Daniel Gilbert

Affective forecasting on Psychology Today

{{Emotion-footer Psychological methodology Behavioral economics