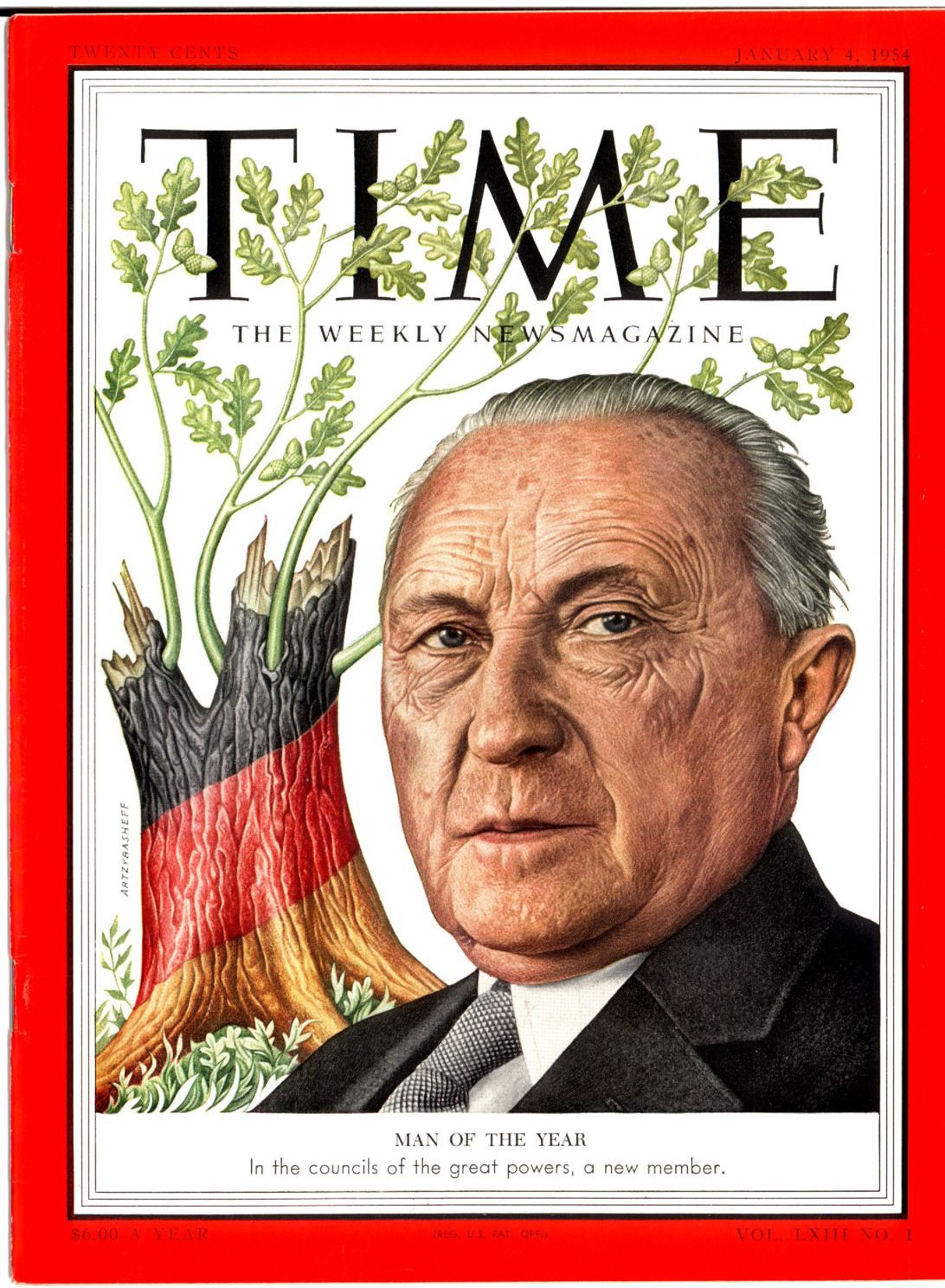

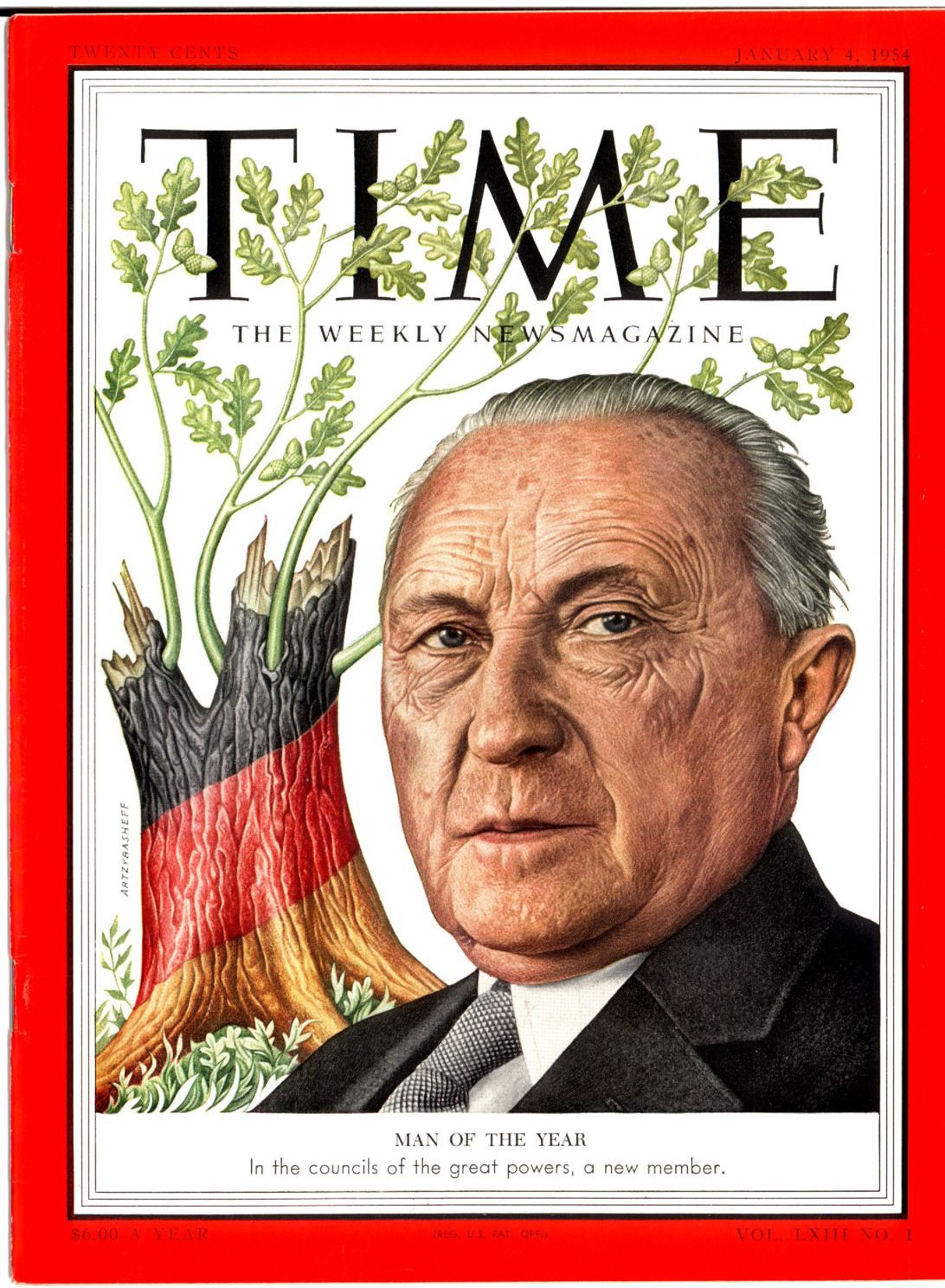

Konrad Hermann Joseph Adenauer (5 January 1876 – 19 April 1967) was a German statesman and politician who served as the first

chancellor of West Germany from 1949 to 1963. From 1946 to 1966, he was the first leader of the

Christian Democratic Union (CDU), a newly founded

Christian democratic

Christian democracy is an ideology inspired by Christian social teaching to respond to the challenges of contemporary society and politics.

Christian democracy has drawn mainly from Catholic social teaching and neo-scholasticism, as well ...

party, which became the dominant force in the country under his leadership.

As a devout

Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

, Adenauer was a leading politician of the Catholic

Centre Party in the

Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic, officially known as the German Reich, was the German Reich, German state from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional republic for the first time in history; hence it is also referred to, and unofficially proclai ...

, serving as

Mayor of Cologne (1917–1933) and as president of the

Prussian State Council

The Prussian State Council ( German: ''Preußischer Staatsrat'') was the second chamber of the bicameral legislature of the Free State of Prussia between 1921 and 1933; the first chamber was the Prussian Landtag (). The members of the State Cou ...

. In the early years of the Federal Republic, he switched focus from

denazification to recovery, and led his country to close relations with France, the United Kingdom, and the United States. During his years in power, he worked to restore the

West German economy from the destruction of World War II to a central position in Europe with a

market-based

liberal democracy

Liberal democracy, also called Western-style democracy, or substantive democracy, is a form of government that combines the organization of a democracy with ideas of liberalism, liberal political philosophy. Common elements within a liberal dem ...

, stability, international respect and economic prosperity.

Adenauer belied his age by his intense work habits and his uncanny political instinct. A strong

anti-communist, he was deeply committed to an

Atlanticist foreign policy

Foreign policy, also known as external policy, is the set of strategies and actions a State (polity), state employs in its interactions with other states, unions, and international entities. It encompasses a wide range of objectives, includ ...

and restoring the position of

West Germany

West Germany was the common English name for the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) from its formation on 23 May 1949 until German reunification, its reunification with East Germany on 3 October 1990. It is sometimes known as the Bonn Republi ...

on the world stage. Adenauer was a driving force in reestablishing national military forces (the ) and intelligence services (the

Bundesnachrichtendienst

The Federal Intelligence Service (, ; BND) is the foreign intelligence agency of Germany, directly subordinate to the Federal Chancellery of Germany, Chancellor's Office. The Headquarters of the Federal Intelligence Service, BND headquarters is ...

) in West Germany in 1955 and 1956. He refused the diplomatic recognition of the

German Democratic Republic

East Germany, officially known as the German Democratic Republic (GDR), was a country in Central Europe from Foundation of East Germany, its formation on 7 October 1949 until German reunification, its reunification with West Germany (FRG) on ...

as an East-German state and the

Oder–Neisse line

The Oder–Neisse line (, ) is an unofficial term for the Germany–Poland border, modern border between Germany and Poland. The line generally follows the Oder and Lusatian Neisse rivers, meeting the Baltic Sea in the north. A small portion ...

as a postwar frontier to

Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

. Under Adenauer, West Germany joined

NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO ; , OTAN), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental Transnationalism, transnational military alliance of 32 Member states of NATO, member s ...

. A proponent of

European unity

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated population of over 449million as of 2024. The EU is often desc ...

, he signed the

Treaty of Rome

The Treaty of Rome, or EEC Treaty (officially the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community), brought about the creation of the European Economic Community (EEC), the best known of the European Communities (EC). The treaty was signe ...

in 1957. Adenauer is considered as one of the "

Founding fathers of the European Union

Founding may refer to:

* The formation of a corporation, government, or other organization

* The laying of a building's foundation

* The casting of materials in a mold

See also

* Foundation (disambiguation)

* Incorporation (disambiguation)

...

".

Cologne years

Early life and education

Konrad Adenauer was born on 5 January 1876 in

Cologne

Cologne ( ; ; ) is the largest city of the States of Germany, German state of North Rhine-Westphalia and the List of cities in Germany by population, fourth-most populous city of Germany with nearly 1.1 million inhabitants in the city pr ...

,

Rhenish Prussia, as the third of five children of Johann Konrad Adenauer (1833–1906) and his wife Helene (née Scharfenberg; 1849–1919).

His siblings were August (1872–1952), Johannes (1873–1937), Lilli (1879–1950) and Elisabeth, who died shortly after birth 1880. One of the formative influences of Adenauer's youth was the so-called

Kulturkampf

In the history of Germany, the ''Kulturkampf'' (Cultural Struggle) was the seven-year political conflict (1871–1878) between the Catholic Church in Germany led by Pope Pius IX and the Kingdom of Prussia led by chancellor Otto von Bismarck. Th ...

, the struggle of the Prussian state with the Catholic church, an experience that as related to him by his parents left him with a lifelong dislike for "

Prussianism", and led him like many other Catholic Rhinelanders of the 19th century to deeply resent the

Rhineland

The Rhineland ( ; ; ; ) is a loosely defined area of Western Germany along the Rhine, chiefly Middle Rhine, its middle section. It is the main industrial heartland of Germany because of its many factories, and it has historic ties to the Holy ...

's inclusion in Prussia.

Having a passion for inventing, Adenauer started experimenting with plants in the back garden as a child, which was not welcomed by his father who told him "One should not try to meddle with the Lord's hand", then in 1904 he invented a reaction steam engine which was supposed to filter out dust produced by cars. However, as his hobby of inventing grew ever more costly, Adenauer's activities in this area slowly diminished.

After final school examination (

Abitur

''Abitur'' (), often shortened colloquially to ''Abi'', is a qualification granted at the end of secondary education in Germany. It is conferred on students who pass their final exams at the end of ISCED 3, usually after twelve or thirteen year ...

) in 1894, Adenauer studied law and politics at the universities of

Freiburg

Freiburg im Breisgau or simply Freiburg is the List of cities in Baden-Württemberg by population, fourth-largest city of the German state of Baden-Württemberg after Stuttgart, Mannheim and Karlsruhe. Its built-up area has a population of abou ...

,

Munich

Munich is the capital and most populous city of Bavaria, Germany. As of 30 November 2024, its population was 1,604,384, making it the third-largest city in Germany after Berlin and Hamburg. Munich is the largest city in Germany that is no ...

and

Bonn

Bonn () is a federal city in the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia, located on the banks of the Rhine. With a population exceeding 300,000, it lies about south-southeast of Cologne, in the southernmost part of the Rhine-Ruhr region. This ...

, demonstrating competent but not exceptional academic ability. In 1896, he was mustered for the

Prussian army, but did not pass the physical exam due to chronic respiratory problems he had experienced since childhood. He was a member of several

Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

students' associations. He graduated in 1900,

and afterwards worked as a lawyer at the court in Cologne for four years.

Leader in Cologne

As a devout Catholic, he joined the

Centre Party ( or just ) in 1906 and was elected to Cologne's city government in the same year. In 1909, he became Vice-Mayor of Cologne, an industrial metropolis with a population of 635,000 in 1914. Avoiding the extreme political movements that attracted so many of his generation, Adenauer was committed to bourgeois decency, diligence, order, Christian morals and values, and was dedicated to rooting out disorder, inefficiency, irrationality and political immorality. In 1917, he was unanimously elected as

Mayor of Cologne for a 12-year period, and re-elected in 1929.

By 1931 and whilst Mayor of Cologne, he was also acting Vice President of the German Colonial Society from 1931 to 1933 and said: "The German Empire must strive for the acquisition of colonies. There is too little room in the Empire itself for its large population." Adenauer maintained his colonialist outlook long into his later career as West German Chancellor.

During

World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, he worked closely with the army to maximize the city's role as a rear base of supply and transportation for the Western Front. He paid special attention to the civilian food supply, enabling the residents to avoid the worst of the severe shortages that beset most German cities during 1918–1919. In 1918, he invented a soy-based sausage called the ''Cologne sausage'' to help feed the city. In the face of the collapse of the old regime and the threat of revolution and widespread disorder in late 1918, Adenauer maintained control in Cologne using his good working relationship with the Social Democrats. In a speech on 1 February 1919 Adenauer called for the dissolution of Prussia, and for the Prussian Rhineland to become a new autonomous ''Land'' (state) in the ''Reich''. Adenauer claimed this was the only way to prevent France from annexing the Rhineland. Both the ''Reich'' and Prussian governments were completely against Adenauer's plans for breaking up Prussia. When the terms of the

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was a peace treaty signed on 28 June 1919. As the most important treaty of World War I, it ended the state of war between Germany and most of the Allies of World War I, Allied Powers. It was signed in the Palace ...

were presented to Germany in June 1919, Adenauer again suggested to Berlin his plan for an autonomous Rhineland state and again his plans were rejected by the ''Reich'' government.

He established a good working relationship with the postwar British military authorities, using them to neutralize the

workers' and soldiers' council

A workers' council, also called labour council, is a type of council in a workplace or a locality made up of workers or of temporary and instantly revocable delegates elected by the workers in a locality's workplaces. In such a system of poli ...

that had become an alternative base of power for the city's left wing. During the

Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic, officially known as the German Reich, was the German Reich, German state from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional republic for the first time in history; hence it is also referred to, and unofficially proclai ...

, he was president of the

Prussian State Council

The Prussian State Council ( German: ''Preußischer Staatsrat'') was the second chamber of the bicameral legislature of the Free State of Prussia between 1921 and 1933; the first chamber was the Prussian Landtag (). The members of the State Cou ...

from 1921 to 1933, which was the representation of the

provinces of Prussia

The Provinces of Prussia () were the main administrative divisions of Prussia from 1815 to 1946. Prussia's province system was introduced in the Prussian Reform Movement, Stein-Hardenberg Reforms in 1815, and were mostly organized from duchies an ...

in its legislature.

A major debate had occurred within his Centre Party since 1906 regarding the question of whether it should "leave the tower" (i.e. allow Protestants to join, becoming a multi-faith party) or "stay in the tower" (i.e. continue to be a Catholic-only party). Adenauer was one of the leading advocates of "leaving the tower", which led to a dramatic clash at the 1922 ''

Katholikentag'', the annual meeting of German Catholics under the presidency of Adenauer. Cardinal

Michael von Faulhaber

Michael von Faulhaber (5 March 1869 – 12 June 1952) was a German Catholic prelate who served as list of bishops of Freising and archbishops of Munich and Freising, Archbishop of Munich and Freising for 35 years, from 1917 to his death in 195 ...

publicly admonished Adenauer for wanting to take the ''Zentrum'' "out of the tower".

In mid-October 1923, the Chancellor

Gustav Stresemann

Gustav Ernst Stresemann (; 10 May 1878 – 3 October 1929) was a German statesman during the Weimar Republic who served as Chancellor of Germany#First German Republic (Weimar Republic, 1919–1933), chancellor of Germany from August to November 1 ...

announced that Berlin would cease all financial payments to the Rhineland and that the new currency

''Rentenmark'', which had replaced the now worthless ''Mark'' would not circulate in the Rhineland. To save the Rhineland economy, Adenauer opened talks with the French High Commissioner

Paul Tirard in late October 1923 for a Rhenish republic in a sort of economic union with France which would achieve Franco-German reconciliation, which Adenauer called a "grand design". At the same time, Adenauer clung to the hope that the ''Rentenmark'' might still circulate in the Rhineland. Adenauer's plans came to naught when Stresemann, who was resolutely opposed to Adenauer's "grand design", which he viewed as borderline treason, was able to negotiate an end to the crisis on his own.

In 1926, the ''Zentrum'' suggested Adenauer becoming Chancellor, an offer that he was interested in but ultimately rejected when the

German People's Party insisted that one of the conditions for entering into a coalition under Adenauer's leadership was that

Gustav Stresemann

Gustav Ernst Stresemann (; 10 May 1878 – 3 October 1929) was a German statesman during the Weimar Republic who served as Chancellor of Germany#First German Republic (Weimar Republic, 1919–1933), chancellor of Germany from August to November 1 ...

stay on as Foreign Minister. Adenauer, who disliked Stresemann as "too Prussian," rejected that condition.

Years under the Nazi government

When the

Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party ( or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported the ideology of Nazism. Its precursor ...

won several municipal, state and national elections in between 1930 and 1932, Adenauer, a strong opponent of Adolf Hitler and the Nazis, still believed that improvements in the national economy would make his strategy work: ignore the Nazis and concentrate on the Communist threat. He thought that based on election returns, the Nazis should become part of the Prussian and ''Reich'' governments, even when he was already the target of intense personal attacks. Political maneuverings around the ageing

President Hindenburg then

brought the Nazis to power on 30 January 1933.

By early February, Adenauer finally realized the futility of all discussions and any attempts at compromise with the Nazis. Cologne's city council and the Prussian parliament had been dissolved; on 4 April 1933, he was officially dismissed as mayor and his bank accounts were frozen. "He had no money, no home and no job." After arranging for the safety of his family, he appealed to the abbot of the Benedictine monastery at

Maria Laach for a stay of several months. According to

Albert Speer

Berthold Konrad Hermann Albert Speer (; ; 19 March 1905 – 1 September 1981) was a German architect who served as Reich Ministry of Armaments and War Production, Minister of Armaments and War Production in Nazi Germany during most of W ...

in his book ''

Spandau: The Secret Diaries'',

Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

expressed admiration for Adenauer, noting his civic projects, the building of a road circling the city as a bypass, and a "green belt" of parks. However, both Hitler and Speer concluded that Adenauer's political views and principles made it impossible for him to play any role in

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

.

Adenauer was imprisoned for two days after the

Night of the Long Knives

The Night of the Long Knives (, ), also called the Röhm purge or Operation Hummingbird (), was a purge that took place in Nazi Germany from 30 June to 2 July 1934. Chancellor Adolf Hitler, urged on by Hermann Göring and Heinrich Himmler, ord ...

on 30 June 1934; however, on 10 August 1934, maneuvering for his pension, he wrote a ten-page letter to

Hermann Göring

Hermann Wilhelm Göring (or Goering; ; 12 January 1893 – 15 October 1946) was a German Nazism, Nazi politician, aviator, military leader, and convicted war criminal. He was one of the most powerful figures in the Nazi Party, which gov ...

, the Prussian interior minister. He stated that as Mayor he had violated Prussian laws in order to allow Nazi events in public buildings and Nazi flags to be flown from city flagpoles, and that in 1932 he had declared publicly that the Nazis should join the Reich government in a leading role. At the end of 1932, Adenauer had indeed demanded a joint government by his Zentrum party and the Nazis for Prussia.

During the next two years, Adenauer changed residences often for fear of reprisals against him, while living on the benevolence of friends. With the help of lawyers in August 1937 he was successful in claiming a pension. He received a cash settlement for his house, which had been taken over by the city of Cologne; his unpaid mortgage, penalties and taxes were waived. With reasonable financial security he managed to live in seclusion for some years. After the

failed assassination attempt on Hitler of July 1944, he was imprisoned for a second time as an opponent of the regime. He fell ill and credited , a former municipal worker in Cologne and a communist, with saving his life. Zander, then a section

Kapo of a labor camp near Bonn, discovered Adenauer's name on a deportation list to the East and managed to get him admitted to a hospital. Adenauer was subsequently rearrested (as was his wife), but was released from prison at

Brauweiler in November 1944.

After World War II and the founding of the CDU

Shortly after the war ended, the American occupation forces once again installed him as Mayor of Cologne, which had been heavily

bombed. After the city was transferred into the

British zone of occupation, however, the Director of its military government, General

Gerald Templer

Field marshal (United Kingdom), Field Marshal Sir Gerald Walter Robert Templer (11 September 1898 – 25 October 1979) was a senior British Army officer. He fought in both the world wars and took part against the 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Pales ...

, dismissed Adenauer for incompetence in December 1945. Adenauer considered the Germans the political equals of the occupying Allies, a view that angered Templer. Adenauer's dismissal by the British contributed much to his subsequent political success and allowed him to pursue a policy of alliance with the occupying Allies in the 1950s without facing charges of being a "sell-out".

After being dismissed, Adenauer devoted himself to building a new political party, the

Christian Democratic Union (CDU), which he hoped would embrace both Protestants and Catholics in a single party. According to Adenauer, a Catholic-only party would lead to German politics being dominated by anti-democratic parties yet again. In January 1946, Adenauer initiated a political meeting of the future CDU in the British zone in his role as doyen (the oldest man in attendance, ''Alterspräsident'') and was informally confirmed as its leader. During the Weimar Republic, Adenauer had often been considered a future Chancellor and after 1945, his claims for leadership were even stronger. The other surviving ''Zentrum'' leaders were considered unsuitable for the tasks that lay ahead.

Reflecting his background as a Catholic Rhinelander who had long chafed under Prussian rule, Adenauer believed that

Prussianism was the root cause of National Socialism, and that only by driving out Prussianism could Germany become a democracy. In a December 1946 letter, Adenauer wrote that the Prussian state in the early 19th century had become an "almost God-like entity" that valued state power over the rights of individuals. Adenauer's dislike of Prussia even led him to oppose Berlin as a future capital.

Adenauer viewed the most important battle in the postwar world as between the forces of Christianity and

Marxism

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflict, ...

, especially Communism. Marxism meant both the Communists and the Social Democrats as the latter were officially a Marxist party until the

Bad Godesberg conference of 1959. The same anti-Marxist viewpoints led Adenauer to denounce the Social Democrats as the heirs to Prussianism and National Socialism. Adenauer's ideology was at odds with parts of the CDU, who wished to unite

socialism

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

and

Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion, which states that Jesus in Christianity, Jesus is the Son of God (Christianity), Son of God and Resurrection of Jesus, rose from the dead after his Crucifixion of Jesus, crucifixion, whose ...

. Adenauer worked diligently at building up contacts and support in the CDU over the following years, and he sought with varying success to impose his particular ideology on the party.

Adenauer's leading role in the CDU of the British zone won him a position at the

Parliamentary Council of 1948, which had been called into existence by the Western

Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not an explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are calle ...

to draft a constitution for the three western zones of Germany. He was the chairman of this constitutional convention and vaulted from this position to being chosen as the first head of government once the new "

Basic Law

A basic law is either a codified constitution, or in countries with uncodified constitutions, a law designed to have the effect of a constitution. The term ''basic law'' is used in some places as an alternative to "constitution" and may be inte ...

" had been promulgated in May 1949.

Chancellor of West Germany

First government

The first election to the

Bundestag

The Bundestag (, "Federal Diet (assembly), Diet") is the lower house of the Germany, German Federalism in Germany, federal parliament. It is the only constitutional body of the federation directly elected by the German people. The Bundestag wa ...

of West Germany was

held on 15 August 1949, with the Christian Democrats emerging as the strongest party. There were two clashing visions of a future Germany held by Adenauer and his main rival, the Social Democrat

Kurt Schumacher. Adenauer favored integrating the Federal Republic with other Western states, especially France and the United States in order to fight the

Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

, even if the price of this was the continued division of Germany. Schumacher by contrast, though an anti-communist, wanted to see a united, socialist and neutral Germany. As such, Adenauer was in favor of joining NATO, something that Schumacher strongly opposed.

The Free Democrat

Theodor Heuss

Theodor Heuss (; 31 January 1884 – 12 December 1963) was a German liberal politician who served as the first president of West Germany from 1949 to 1959. His civil demeanour and his cordial nature – something of a contrast to German nati ...

was elected the first

President of the Republic, and Adenauer was elected Chancellor (head of government) on 15 September 1949 with the support of his own CDU, the

Christian Social Union, the liberal

Free Democratic Party, and the right-wing

German Party. It was said that Adenauer was elected Chancellor by the new German parliament by "a majority of one vote – his own".

At age 73, it was thought that Adenauer would only be a caretaker Chancellor.

However, he would go on to hold this post for 14 years, a period spanning most of the preliminary phase of the

Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

. During this period, the post-war division of Germany was consolidated with the establishment of two separate German states, the

Federal Republic of Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen constituent states have a total population of over 84 ...

(West Germany) and the

German Democratic Republic

East Germany, officially known as the German Democratic Republic (GDR), was a country in Central Europe from Foundation of East Germany, its formation on 7 October 1949 until German reunification, its reunification with West Germany (FRG) on ...

(East Germany).

In the controversial selection for a "provisional capital" of the

Federal Republic of Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen constituent states have a total population of over 84 ...

, Adenauer championed

Bonn

Bonn () is a federal city in the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia, located on the banks of the Rhine. With a population exceeding 300,000, it lies about south-southeast of Cologne, in the southernmost part of the Rhine-Ruhr region. This ...

over

Frankfurt am Main

Frankfurt am Main () is the most populous city in the States of Germany, German state of Hesse. Its 773,068 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the List of cities in Germany by population, fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located in the forela ...

. The British had agreed to detach Bonn from their zone of occupation and convert the area to an autonomous region wholly under German sovereignty; the Americans were not prepared to grant the same for Frankfurt. He also resisted the claims of

Heidelberg

Heidelberg (; ; ) is the List of cities in Baden-Württemberg by population, fifth-largest city in the States of Germany, German state of Baden-Württemberg, and with a population of about 163,000, of which roughly a quarter consists of studen ...

, which had better communications and had survived the war in better condition; partly because the Nazis had been popular there before they came to power and partly, as he said, because the world would not take them seriously if they set up their state in a city that was the setting for ''

The Student Prince

''The Student Prince'' is an operetta in a prologue and four acts with music by Sigmund Romberg and book and lyrics by Dorothy Donnelly. It is based on Wilhelm Meyer-Förster's play ''Old Heidelberg (play), Old Heidelberg''. The piece has a scor ...

'', at the time a popular American operetta based on the drinking culture of

German student fraternities.

As chancellor, Adenauer tended to make most major decisions himself, treating his ministers as mere extensions of his authority. While this tendency decreased under his successors, it established the image of West Germany (and later reunified Germany) as a "chancellor democracy".

Ending denazification

In a speech on 20 September 1949, Adenauer denounced the entire

denazification process pursued by the Allied military governments, announcing in the same speech that he was planning to bring in an amnesty law for the Nazi war criminals and he planned to apply to "the High Commissioners for a corresponding amnesty for punishments imposed by the Allied military courts". Adenauer argued the continuation of denazification would "foster a growing and extreme nationalism" as the millions who supported the Nazi regime would find themselves excluded from German life forever. He also demanded an "end to this sniffing out of Nazis." By 31 January 1951, the amnesty legislation had benefited 792,176 people. They included 3,000 functionaries of the SA, the SS, and the Nazi Party who participated in dragging victims to jails and camps; 20,000 Nazis sentenced for "deeds against life" (presumably murder); 30,000 sentenced for causing bodily injury, and about 5,200 charged with "crimes and misdemeanors in office.

Opposition to the Oder–Neisse Line

The Adenauer government refused to accept the

Oder–Neisse line

The Oder–Neisse line (, ) is an unofficial term for the Germany–Poland border, modern border between Germany and Poland. The line generally follows the Oder and Lusatian Neisse rivers, meeting the Baltic Sea in the north. A small portion ...

as Germany's eastern frontier. This refusal was in large part motivated by his desire to win the votes of

expellees and right-wing nationalists to the CDU, which is why he supported , i.e. the right of expellees to return to their former homes. It was also intended to be a deal-breaker if negotiations ever began to reunite Germany on terms that Adenauer considered unfavorable such as the neutralization of Germany as Adenauer knew well that the Soviets would never revise the Oder–Neisse line. Privately, Adenauer considered Germany's eastern provinces to be lost forever.

Advocacy for European Coal and Steel Community

At the

Petersberg Agreement

The Petersberg Agreement is an international treaty that extended the rights of the government of West Germany vis-a-vis the occupying forces of the United Kingdom, France, and the United States. It is viewed as the first major step of West Germa ...

in November 1949 he achieved some of the first concessions granted by the Allies, such as a decrease in the number of factories to be dismantled, but in particular his agreement to join the

International Authority for the Ruhr

The International Authority for the Ruhr (IAR) was an international body established in 1949 by the Western Allies to regulate the coal and steel industries of the Ruhr area in West Germany. Its seat was in Düsseldorf.

The Ruhr Authority was ...

led to heavy criticism. In the following debate in parliament Adenauer stated:

:

''The Allies have told me that dismantling would be stopped only if I satisfy the Allied desire for security, does the Socialist Party want dismantling to go on to the bitter end?''

The opposition leader

Kurt Schumacher responded by labeling Adenauer "Chancellor of the Allies", accusing Adenauer of putting good relations with the West for the sake of the Cold War ahead of German national interests.

After a year of negotiations, the

Treaty of Paris was signed on 18 April 1951 establishing the

European Coal and Steel Community

The European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) was a European organization created after World War II to integrate Europe's coal and steel industries into a single common market based on the principle of supranationalism which would be governe ...

. The treaty was unpopular in Germany where it was seen as a French attempt to take over German industry. The treaty conditions were favorable to the French, but for Adenauer, the only thing that mattered was European integration. Adenauer was keen to see Britain join the European Coal and Steel Community as he believed the more free-market British would counterbalance the influence of the more

''dirigiste'' French, and to achieve that purpose he visited London in November 1951 to meet with Prime Minister

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

. Churchill said Britain would not join the European Coal and Steel Community because doing so would mean sacrificing relations with the U.S. and Commonwealth.

German rearmament

From the beginning of his Chancellorship, Adenauer had been pressing for

German rearmament

German rearmament (''Aufrüstung'', ) was a policy and practice of rearmament carried out by Germany from 1918 to 1939 in violation of the Treaty of Versailles, which required German disarmament after World War I to prevent it from starting an ...

. After the outbreak of the

Korean War

The Korean War (25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953) was an armed conflict on the Korean Peninsula fought between North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea; DPRK) and South Korea (Republic of Korea; ROK) and their allies. North Korea was s ...

on 25 June 1950, the U.S. and Britain agreed that West Germany had to be rearmed to strengthen the defenses of Western Europe against a possible Soviet invasion. Further contributing to the crisis atmosphere of 1950 was the bellicose rhetoric of the East German leader

Walter Ulbricht

Walter Ernst Paul Ulbricht (; ; 30 June 18931 August 1973) was a German communist politician. Ulbricht played a leading role in the creation of the Weimar republic, Weimar-era Communist Party of Germany (KPD) and later in the early development ...

, who proclaimed the reunification of Germany under communist rule to be imminent. To soothe French fears of German rearmament, the French Premier

René Pleven

René Jean Pleven (; 15 April 190113 January 1993) was a notable political figure of the French Resistance and Fourth Republic. An early associate of Jean Monnet then member of the Free French led by Charles de Gaulle, he took a leading role i ...

suggested the so-called

Pleven plan in October 1950 under which the Federal Republic would have its military forces function as part of the armed wing of the multinational

European Defense Community (EDC). Adenauer deeply disliked the "Pleven plan", but was forced to support it when it became clear that this plan was the only way the French would agree to German rearmament.

Amnesty and employment of Nazis

In 1950, a major controversy broke out when it emerged that Adenauer's State Secretary

Hans Globke had played a major role in drafting anti-semitic

Nuremberg Race Laws in Nazi Germany. Adenauer kept Globke on as State Secretary as part of his strategy of integration. Starting in August 1950, Adenauer began to pressure the Western Allies to free all of the war criminals in their custody, especially those from the

Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the German Army (1935–1945), ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmac ...

, whose continued imprisonment he claimed made

West German rearmament impossible. Adenauer had been opposed to the

Nuremberg Trials #REDIRECT Nuremberg trials

{{redirect category shell, {{R from other capitalisation{{R from move ...

in 1945–46, and after becoming Chancellor, he demanded the release of the so-called "Spandau Seven", as the seven war criminals convicted at Nuremberg and imprisoned at

Spandau Prison

Spandau Prison was a former military prison located in the Spandau borough of West Berlin (present-day Berlin, Germany). Built in 1876, it became a proto-concentration camp under Nazi Germany. After the Second World War, it held seven top Nazi l ...

were known.

In October 1950, Adenauer received the so-called "

Himmerod memorandum" drafted by four former Wehrmacht generals at the

Himmerod Abbey that linked freedom for German war criminals as the price of German rearmament, along with public statements from the Allies that the

Wehrmacht committed no war crimes in World War II. The Allies were willing to do whatever necessary to get the much-needed German rearmament underway, and in January 1951, General

Dwight Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

, commander of NATO forces, issued a statement which declared the great majority of the Wehrmacht had acted honorably.

On 2 January 1951, Adenauer met with the American High Commissioner,

John J. McCloy

John Jay McCloy (March 31, 1895 – March 11, 1989) was an American lawyer, diplomat, banker, and high-ranking bureaucrat. He served as United States Assistant Secretary of War, Assistant Secretary of War during World War II under Henry L. Stims ...

, to argue that executing the

Landsberg prisoners would ruin forever any effort at having the Federal Republic play its role in the Cold War. At the time, American occupation authorities had 28 Nazi war criminals left on death row in their custody. In response to Adenauer's demands and pressure from the German public, McCloy and

Thomas T. Handy on 31 January 1951 reduced the death sentences of all but the 7 worst offenders.

By 1951 laws were passed by the

Bundestag

The Bundestag (, "Federal Diet (assembly), Diet") is the lower house of the Germany, German Federalism in Germany, federal parliament. It is the only constitutional body of the federation directly elected by the German people. The Bundestag wa ...

ending denazification.

Denazification

Denazification () was an Allied initiative to rid German and Austrian society, culture, press, economy, judiciary, and politics of the Nazi ideology following the Second World War. It was carried out by removing those who had been Nazi Par ...

was viewed by the United States as counterproductive and ineffective, and its demise was not opposed. Adenauer's intention was to switch government policy to reparations and compensation for the victims of Nazi rule (''

Wiedergutmachung

''Wiedergutmachung'' (; German: "compensation", "restitution", lit: "make good again") refers to the reparations that the German government agreed to pay in 1953 to the direct survivors of the Holocaust, and to those who were made to work at ...

'').

Officials were allowed to retake jobs in civil service, with the exception of people assigned to Group I (Major Offenders) and II (Offenders) during the denazification review process.

[Art, David, ''The politics of the Nazi past in Germany and Austria'', Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005, pp. 53–55] Adenauer pressured his rehabilitated ex-Nazis by threatening that stepping out of line could trigger the reopening of individual de-Nazification prosecutions. The construction of a "competent Federal Government effectively from a standing start was one of the greatest of Adenauer's formidable achievements".

Contemporary critics accused Adenauer of cementing the division of Germany, sacrificing reunification and the recovery of territories lost in the westward shift of

Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

and the

Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

with his determination to secure the Federal Republic to the West. Adenauer's German policy was based upon ''Politik der Stärke'' (Policy of Strength), and upon the so-called "magnet theory", in which a prosperous, democratic West Germany integrated with the West would act as a "magnet" that would eventually bring down the East German regime.

Rejecting the reunification offer

In 1952, the

Stalin Note, as it became known, "caught everybody in the West by surprise". It offered to unify the two German entities into a single, neutral state with its own, non-aligned national army to effect superpower disengagement from

Central Europe

Central Europe is a geographical region of Europe between Eastern Europe, Eastern, Southern Europe, Southern, Western Europe, Western and Northern Europe, Northern Europe. Central Europe is known for its cultural diversity; however, countries in ...

. Adenauer and his cabinet were unanimous in their rejection of the Stalin overture; they shared the Western Allies' suspicion about the genuineness of that offer and supported the Allies in their cautious replies. Adenauer's flat rejection was, however, still out of step with public opinion; he then realized his mistake and he started to ask questions. Critics denounced him for having missed an opportunity for

German reunification

German reunification () was the process of re-establishing Germany as a single sovereign state, which began on 9 November 1989 and culminated on 3 October 1990 with the dissolution of the East Germany, German Democratic Republic and the int ...

. The Soviets sent a second note, courteous in tone. Adenauer by then understood that "all opportunity for initiative had passed out of his hands," and the matter was put to rest by the Allies. Given the realities of the

Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

, German reunification and recovery of

lost territories in the east were not realistic goals as both of Stalin's notes specified the retention of the existing "Potsdam"-decreed boundaries of Germany.

Reparation to victims of Nazi Germany

Adenauer recognized the obligation of the West German government to compensate

Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

for

The Holocaust

The Holocaust (), known in Hebrew language, Hebrew as the (), was the genocide of History of the Jews in Europe, European Jews during World War II. From 1941 to 1945, Nazi Germany and Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy ...

. West Germany started negotiations with Israel for restitution of lost property and the payment of damages to victims of Nazi persecution. In the , West Germany agreed to pay compensation to Israel. Jewish claims were bundled in the

Jewish Claims Conference, which represented the Jewish victims of Nazi Germany. West Germany then initially paid about 3 billion

Mark

Mark may refer to:

In the Bible

* Mark the Evangelist (5–68), traditionally ascribed author of the Gospel of Mark

* Gospel of Mark, one of the four canonical gospels and one of the three synoptic gospels

Currencies

* Mark (currency), a currenc ...

to Israel and about 450 million to the Claims Conference, although payments continued after that, as new claims were made.

In the face of severe opposition both from the public and from his own cabinet, Adenauer was only able to get the reparations agreement ratified by the ''Bundestag'' with the support of the SPD.

[Moeller, Robert ''War Stories: The Search for a Usable Past in the Federal Republic of Germany'', Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2001 pages 26–27.] Israeli public opinion was divided over accepting the money, but ultimately the fledgling state under

David Ben-Gurion

David Ben-Gurion ( ; ; born David Grün; 16 October 1886 – 1 December 1973) was the primary List of national founders, national founder and first Prime Minister of Israel, prime minister of the State of Israel. As head of the Jewish Agency ...

agreed to take it, opposed by political parties such as

Herut

Herut () was the major conservative nationalist political party in Israel from 1948 until its formal merger into Likud in 1988. It was an adherent of Revisionist Zionism. Some of their policies were compared to those of the Nazi party.

Early y ...

, who were against such treaties.

Assassination attempt

On 27 March 1952, a package addressed to Chancellor Adenauer exploded in the

Munich

Munich is the capital and most populous city of Bavaria, Germany. As of 30 November 2024, its population was 1,604,384, making it the third-largest city in Germany after Berlin and Hamburg. Munich is the largest city in Germany that is no ...

Police Headquarters, killing one Bavarian police officer, Karl Reichert. Investigations revealed the mastermind behind the assassination attempt to be

Menachem Begin

Menachem Begin ( ''Menaḥem Begin'', ; (Polish documents, 1931–1937); ; 16 August 1913 – 9 March 1992) was an Israeli politician, founder of both Herut and Likud and the prime minister of Israel.

Before the creation of the state of Isra ...

, who would later become the Prime Minister of

Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

. Begin had been the commander of

Irgun

The Irgun (), officially the National Military Organization in the Land of Israel, often abbreviated as Etzel or IZL (), was a Zionist paramilitary organization that operated in Mandatory Palestine between 1931 and 1948. It was an offshoot of th ...

and at that time headed

Herut

Herut () was the major conservative nationalist political party in Israel from 1948 until its formal merger into Likud in 1988. It was an adherent of Revisionist Zionism. Some of their policies were compared to those of the Nazi party.

Early y ...

and was a member of the

Knesset

The Knesset ( , ) is the Unicameralism, unicameral legislature of Israel.

The Knesset passes all laws, elects the President of Israel, president and Prime Minister of Israel, prime minister, approves the Cabinet of Israel, cabinet, and supe ...

. His goal was to put pressure on the German government and prevent the signing of the

Reparations Agreement between Israel and West Germany

The Reparations Agreement between Israel and the Federal Republic of Germany (, "Luxembourg Agreement", or ', "''Wiedergutmachung'' Agreement"; , "Reparations Agreement") was signed on September 10, 1952, and entered in force on March 27, 1953.Hon ...

, which he vehemently opposed. The West German government kept all proof under seal in order to prevent

antisemitic

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

responses from the German public.

Second government

Interior affairs

When the

East German uprising of 1953 was harshly suppressed by the Red Army in June 1953, Adenauer took political advantage of the situation and was handily re-elected to a second term as Chancellor. The CDU/CSU came up one seat short of an outright majority. Adenauer could thus have governed in a coalition with only one other party, but retained/gained the support of nearly all of the parties in the Bundestag that were to the right of the SPD.

The

German Restitution Laws () were passed in 1953 that allowed some victims of Nazi prosecution to claim restitution. Under the 1953 restitution law, those who had suffered for "racial, religious or political reasons" could collect compensation, which were defined in such a way as to sharply limit the number of people entitled to collect compensation.

In November 1954, Adenauer's lobbying efforts on behalf of the "Spandau Seven" finally bore fruit with the release of

Konstantin von Neurath

Konstantin Hermann Karl Freiherr von Neurath (2 February 1873 – 14 August 1956) was a German politician, diplomat and convicted Nazi war criminal who served as Foreign Minister of Germany between 1932 and 1938.

Born to a Swabian noble famil ...

. Adenauer congratulated Neurath on his release, sparking controversy all over the world. At the same time, Adenauer's efforts to win freedom for Admiral

Karl Dönitz

Karl Dönitz (; 16 September 1891 – 24 December 1980) was a German grand admiral and convicted war criminal who, following Adolf Hitler's Death of Adolf Hitler, suicide, succeeded him as head of state of Nazi Germany during the Second World ...

ran into staunch opposition from the British Permanent Secretary at the Foreign Office,

Ivone Kirkpatrick, who argued Dönitz would be an active danger to German democracy. Adenauer then traded with Kirkpatrick no early release for Admiral Dönitz with an early release for Admiral

Erich Raeder

Erich Johann Albert Raeder (24 April 1876 – 6 November 1960) was a German admiral who played a major role in the naval history of World War II and was convicted of war crimes after the war. He attained the highest possible naval rank, that of ...

on medical grounds.

Adenauer is closely linked to the implementation of an enhanced

pension

A pension (; ) is a fund into which amounts are paid regularly during an individual's working career, and from which periodic payments are made to support the person's retirement from work. A pension may be either a " defined benefit plan", wh ...

system, which ensured unparalleled prosperity for retired people. Along with his Minister for Economic Affairs and successor

Ludwig Erhard

Ludwig Wilhelm Erhard (; 4 February 1897 – 5 May 1977) was a German politician and economist affiliated with the Christian Democratic Union of Germany, Christian Democratic Union (CDU), and Chancellor of Germany (1949–), chancellor of West Ge ...

, the West German model of a "

social market economy

The social market economy (SOME; ), also called Rhine capitalism, Rhine-Alpine capitalism, the Rhenish model, and social capitalism, is a socioeconomic model combining a free-market capitalist economic system with social policies and enough re ...

" (a

mixed economy

A mixed economy is an economic system that includes both elements associated with capitalism, such as private businesses, and with socialism, such as nationalized government services.

More specifically, a mixed economy may be variously de ...

with

capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

moderated by elements of

social welfare

Welfare spending is a type of government support intended to ensure that members of a society can meet basic human needs such as food and shelter. Social security may either be synonymous with welfare, or refer specifically to social insurance p ...

and

Catholic social teaching

Catholic social teaching (CST) is an area of Catholic doctrine which is concerned with human dignity and the common good in society. It addresses oppression, the role of the state, subsidiarity, social organization, social justice, and w ...

) allowed for the boom period known as the ('economic miracle') that produced broad prosperity, but Adenauer acted more leniently towards the trade unions and employers' associations than Erhard. The Adenauer era witnessed a dramatic rise in the standard of living of average Germans, with real wages doubling between 1950 and 1963. This rising affluence was accompanied by a 20% fall in working hours during that same period, together with a fall in the unemployment rate from 8% in 1950 to 0.4% in 1965. in addition, an advanced welfare state was established.

Military affairs

In the spring of 1954, opposition to the

Pleven plan grew within the French

National Assembly

In politics, a national assembly is either a unicameral legislature, the lower house of a bicameral legislature, or both houses of a bicameral legislature together. In the English language it generally means "an assembly composed of the repr ...

., and in August 1954, it died when an alliance of conservatives and Communists in the National Assembly joined forces to reject the EDC treaty under the grounds that West German rearmament in any form was an unacceptable danger to France.

The British Prime Minister

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

told Adenauer that Britain would ensure that West German rearmament would happen, regardless if the National Assembly ratified the EDC treaty or not, and Foreign Secretary

Anthony Eden

Robert Anthony Eden, 1st Earl of Avon (12 June 1897 – 14 January 1977) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party from 1955 until his resignation in 1957.

Achi ...

used the failure of the EDC to argue for independent West German rearmament and West German NATO membership. Thanks in part to Adenauer's success in rebuilding West Germany's image, the British proposal met with considerable approval. In the ensuing

London conference, Eden assisted Adenauer by promising the French that Britain would always maintain at least four divisions in the

British Army of the Rhine

British Army of the Rhine (BAOR) was the name given to British Army occupation forces in the Rhineland, West Germany, after the First and Second World Wars, and during the Cold War, becoming part of NATO's Northern Army Group (NORTHAG) tasked ...

as long as there was a Soviet threat, with the strengthened British forces also aimed implicitly against any German revanchism. Adenauer then promised that Germany would never seek to have nuclear, chemical and biological weapons as well as capital ships, strategic bombers, long-range artillery, and guided missiles, although these promises were non-binding. The French had been assuaged that West German rearmament would be no threat to France. Additionally, Adenauer promised that the West German military would be under the operational control of NATO general staff, though ultimate control would rest with the West German government; and that above all he would never violate the strictly defensive NATO charter and invade East Germany to achieve German reunification.

In May 1955, West Germany joined NATO and in November a West German military, the , was founded. Though Adenauer made use of a number of former generals and admirals in the , he saw the as a new force with no links to the past, and wanted it to be kept under

civilian control at all times. To achieve these aims, Adenauer gave a great deal of power to the military reformer

Wolf Graf von Baudissin.

Adenauer reached an agreement for his "nuclear ambitions" with a NATO Military Committee in December 1956 that stipulated West German forces were to be "equipped for

nuclear warfare

Nuclear warfare, also known as atomic warfare, is a War, military conflict or prepared Policy, political strategy that deploys nuclear weaponry. Nuclear weapons are Weapon of mass destruction, weapons of mass destruction; in contrast to conven ...

". Concluding that the United States would eventually pull out of Western Europe, Adenauer pursued nuclear cooperation with other countries. The French government then proposed that France, West Germany and Italy jointly develop and produce

nuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission or atomic bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear weapon), producing a nuclear exp ...

s and

delivery systems, and an agreement was signed in April 1958. With the ascendancy of

Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French general and statesman who led the Free France, Free French Forces against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Government of the French Re ...

, the agreement for joint production and control was shelved indefinitely. President

John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), also known as JFK, was the 35th president of the United States, serving from 1961 until his assassination in 1963. He was the first Roman Catholic and youngest person elected p ...

, an ardent foe of

nuclear proliferation

Nuclear proliferation is the spread of nuclear weapons to additional countries, particularly those not recognized as List of states with nuclear weapons, nuclear-weapon states by the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, commonl ...

, considered sales of such weapons moot since "in the event of war the United States would, from the outset, be prepared to defend the Federal Republic." The physicists of the

Max Planck Institute

The Max Planck Society for the Advancement of Science (; abbreviated MPG) is a formally independent non-governmental and non-profit association of German research institutes. Founded in 1911 as the Kaiser Wilhelm Society, it was renamed to the M ...

for Theoretical Physics at

Göttingen

Göttingen (, ; ; ) is a college town, university city in Lower Saxony, central Germany, the Capital (political), capital of Göttingen (district), the eponymous district. The River Leine runs through it. According to the 2022 German census, t ...

and other renowned universities would have had the scientific capability for in-house development, but the will was absent, nor was there public support. With Adenauer's fourth-term election in November 1961 and the end of his chancellorship in sight, his "nuclear ambitions" began to taper off.

Foreign policy

In return for the release of the last German prisoners of war in 1955, the Federal Republic established diplomatic relations with the

USSR

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

, but refused to recognize East Germany and broke off diplomatic relations with countries (e.g.,

Yugoslavia

, common_name = Yugoslavia

, life_span = 1918–19921941–1945: World War II in Yugoslavia#Axis invasion and dismemberment of Yugoslavia, Axis occupation

, p1 = Kingdom of SerbiaSerbia

, flag_p ...

) that established relations with the East German régime. Adenauer was also ready to consider the

Oder–Neisse line

The Oder–Neisse line (, ) is an unofficial term for the Germany–Poland border, modern border between Germany and Poland. The line generally follows the Oder and Lusatian Neisse rivers, meeting the Baltic Sea in the north. A small portion ...

as the German border in order to pursue a more flexible policy with Poland but he did not command sufficient domestic support for this, and opposition to the Oder–Neisse line continued, causing considerable disappointment among Adenauer's Western allies.

In 1956, during the

Suez Crisis

The Suez Crisis, also known as the Second Arab–Israeli War, the Tripartite Aggression in the Arab world and the Sinai War in Israel, was a British–French–Israeli invasion of Egypt in 1956. Israel invaded on 29 October, having done so w ...

, Adenauer fully supported the Anglo-French-Israeli attack on Egypt, arguing to his Cabinet that Egyptian President

Gamal Abdel Nasser

Gamal Abdel Nasser Hussein (15 January 1918 – 28 September 1970) was an Egyptian military officer and revolutionary who served as the second president of Egypt from 1954 until his death in 1970. Nasser led the Egyptian revolution of 1952 a ...

was a pro-Soviet force that needed to be cut down to size. Adenauer was appalled that the Americans had come out against the attack on Egypt alongside the Soviets, which led Adenauer to fear that the United States and Soviet Union would "carve up the world" with no thought for European interests.

At the height of the Suez crisis, Adenauer visited Paris to meet the French Premier

Guy Mollet

Guy Alcide Mollet (; 31 December 1905 – 3 October 1975) was a French politician. He led the socialist French Section of the Workers' International (SFIO) from 1946 to 1969 and was the French Prime Minister from 1956 to 1957.

As Prime Ministe ...

in a show of moral support for France. The day before Adenauer arrived in Paris, the Soviet Premier

Nikolai Bulganin

Nikolai Alexandrovich Bulganin (; – 24 February 1975) was the Premier of the Soviet Union from 1955 to 1958. He also served as Minister of Defense (Soviet Union), Minister of Defense, following service in the Red Army during World War II.

...

sent the so-called "Bulganin letters" to the leaders of Britain, France, and Israel threatening nuclear strikes if they did not end the war against Egypt. The news of the "Bulganin letters" reached Adenauer mid-way on the train trip to Paris. The threat of a Soviet nuclear strike that could destroy Paris at any moment added considerably to the tension of the summit. The Paris summit helped to strengthen the bond between Adenauer and the French, who saw themselves as fellow European powers living in a world dominated by Washington and Moscow.

Adenauer was deeply shocked by the Soviet threat of nuclear strikes against Britain and France, and even more so by the apparent quiescent American response to the Soviet threat of nuclear annihilation against two of NATO's key members. As a result, Adenauer became more interested in the French idea of a European "Third Force" in the Cold War as an alternative security policy. This helped to lead to the formation of the

European Economic Community

The European Economic Community (EEC) was a regional organisation created by the Treaty of Rome of 1957,Today the largely rewritten treaty continues in force as the ''Treaty on the functioning of the European Union'', as renamed by the Lisbo ...

in 1957, which was intended to be the foundation stone of the European "Third Force".

Adenauer's achievements include the establishment of a stable democracy in West Germany and a lasting reconciliation with

France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, culminating in the

Élysée Treaty

The Élysée Treaty was a treaty of friendship between France and West Germany, signed by President Charles de Gaulle and Chancellor Konrad Adenauer on 22 January 1963 at the Élysée Palace in Paris. With the signing of this treaty, Germ ...

. His political commitment to the Western powers achieved full sovereignty for West Germany, which was formally laid down in the

General Treaty

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air and space forces, marines or naval infantry.

In some usages, the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". OED Online. Ma ...

, although there remained Allied restrictions concerning the status of a potentially reunited Germany and the state of emergency in West Germany. Adenauer firmly integrated the country with the emerging Euro-Atlantic community (

NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO ; , OTAN), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental Transnationalism, transnational military alliance of 32 Member states of NATO, member s ...

and the

Organisation for European Economic Cooperation

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD; , OCDE) is an intergovernmental organization with 38 member countries, founded in 1961 to stimulate economic progress and world trade. It is a forum whose member countries ...

).

Third government

In 1957 the

Saarland

Saarland (, ; ) is a state of Germany in the southwest of the country. With an area of and population of 990,509 in 2018, it is the smallest German state in area apart from the city-states of Berlin, Bremen, and Hamburg, and the smallest in ...

was reintegrated into Germany as a federal state of the Federal Republic. The election of 1957 essentially dealt with national matters. His re-election campaign centered around the slogan "Keine Experimente" ''(No Experiments)'' in response to the

democratic experimentalism reform proposed by his opponents.

Riding a wave of popularity from the return of the last

POWs

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of war for a ...

from Soviet labor camps, as well as an extensive pension reform, Adenauer led the CDU/CSU to an outright majority, something never previously achieved in a free German election. In 1957, the Federal Republic signed the

Treaty of Rome

The Treaty of Rome, or EEC Treaty (officially the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community), brought about the creation of the European Economic Community (EEC), the best known of the European Communities (EC). The treaty was signe ...

and became a founding member of the

European Economic Community

The European Economic Community (EEC) was a regional organisation created by the Treaty of Rome of 1957,Today the largely rewritten treaty continues in force as the ''Treaty on the functioning of the European Union'', as renamed by the Lisbo ...

. In September 1958, Adenauer first met President

Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French general and statesman who led the Free France, Free French Forces against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Government of the French Re ...

of France, who was to become a close friend and ally in pursuing Franco-German rapprochement. Adenauer saw de Gaulle as a "rock" and the only foreign leader whom he could completely trust.

In response to the

Ulm Einsatzkommando trial in 1958, Adenauer set up the

Central Office of the State Justice Administrations for the Investigation of National Socialist Crimes.

[Taylor, Frederick ''Exorcising Hitler'', London: Bloomsbury Press, 2011 page 373.]

On 27 November 1958

another Berlin crisis broke out when

Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and the Premier of the Soviet Union, Chai ...

submitted an

ultimatum

An ; ; : ultimata or ultimatums) is a demand whose fulfillment is requested in a specified period of time and which is backed up by a coercion, threat to be followed through in case of noncompliance (open loop). An ultimatum is generally the ...

with a six-month expiry date to Washington, London and Paris, where he demanded that the Allies pull all their forces out of West Berlin and agree that West Berlin become a "free city", or else he would sign a separate peace treaty with East Germany. Adenauer was opposed to any sort of negotiations with the Soviets, arguing if only the West were to hang tough long enough, Khrushchev would back down. As the 27 May deadline approached, the crisis was defused by the British Prime Minister

Harold Macmillan

Maurice Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton (10 February 1894 – 29 December 1986), was a British statesman and Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1957 to 1963. Nickn ...

, who visited

Moscow

Moscow is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Russia by population, largest city of Russia, standing on the Moskva (river), Moskva River in Central Russia. It has a population estimated at over 13 million residents with ...

to meet with Khrushchev and managed to extend the deadline while not committing himself or the other Western powers to concessions. Adenauer believed Macmillan to be a spineless "appeaser", who had made a secret deal with Khrushchev at the expense of the Federal Republic.

[Thorpe, D.R. ''Supermac'', London: Chatto & Windus, 2010 page 428]

Adenauer tarnished his image when he announced he would run for the office of

federal president in 1959, only to pull out when he discovered that he did not have political backing to strengthen the office of president and change the balance of power. After his reversal he supported the nomination of

Heinrich Lübke as the CDU presidential candidate whom he believed weak enough not to interfere with his actions as Federal Chancellor. One of Adenauer's reasons for not pursuing the presidency was his fear that Ludwig Erhard, whom Adenauer thought little of, would become the new chancellor.

By early 1959, Adenauer came under renewed pressure from his Western allies to recognize the

Oder–Neisse line

The Oder–Neisse line (, ) is an unofficial term for the Germany–Poland border, modern border between Germany and Poland. The line generally follows the Oder and Lusatian Neisse rivers, meeting the Baltic Sea in the north. A small portion ...

, with the Americans being especially insistent. Adenauer gave his "explicit and unconditional approval" to the idea of

non-aggression pact

A non-aggression pact or neutrality pact is a treaty between two or more states/countries that includes a promise by the signatories not to engage in military action against each other. Such treaties may be described by other names, such as a t ...

s in late January 1959, which effectively meant recognising the Oder–Neisse line, since realistically speaking Germany could only regain the lost territories through force. After Adenauer's intention to sign non-aggression pacts with Poland and Czechoslovakia became clear, the

German expellee lobby swung into action and organized protests all over the Federal Republic while bombarding the offices of Adenauer and other members of the cabinet with thousands of letters, telegrams and telephone calls promising never to vote CDU again if the non-aggression pacts were signed. Faced with this pressure, Adenauer promptly capitulated to the expellee lobby.

In late 1959, a controversy broke out when it emerged that

Theodor Oberländer, the Minister of Refugees since 1953 and one of the most powerful leaders of the expellee lobby, had committed war crimes against Jews and Poles during World War II. Despite his past, on 10 December 1959, a statement was released to the press declaring that "Dr. Oberländer has the full confidence of the Adenauer cabinet".

[Tetens, T.H. ''The New Germany and the Old Nazis'', New York: Random House, 1961 page 192] Other Christian Democrats made it clear to Adenauer that they would like to see Oberländer out of the cabinet, and finally in May 1960 Oberländer resigned.

Fourth government

In 1961, Adenauer had his concerns about both the status of Berlin and US leadership confirmed, as the Soviets and East Germans built the Berlin Wall. Adenauer had come into the year distrusting the new US president,

John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), also known as JFK, was the 35th president of the United States, serving from 1961 until his assassination in 1963. He was the first Roman Catholic and youngest person elected p ...

. He doubted Kennedy's commitment to a free Berlin and a unified Germany and considered him undisciplined and naïve. For his part, Kennedy thought that Adenauer was a relic of the past. Their strained relationship impeded effective Western action on Berlin during 1961.

The construction of the

Berlin Wall

The Berlin Wall (, ) was a guarded concrete Separation barrier, barrier that encircled West Berlin from 1961 to 1989, separating it from East Berlin and the East Germany, German Democratic Republic (GDR; East Germany). Construction of the B ...

in August 1961 and the sealing of borders by the East Germans made Adenauer's government look weak. Adenauer continued his campaign trail and made a disastrous misjudgement in a speech on 14 August 1961 in

Regensburg

Regensburg (historically known in English as Ratisbon) is a city in eastern Bavaria, at the confluence of the rivers Danube, Naab and Regen (river), Regen, Danube's northernmost point. It is the capital of the Upper Palatinate subregion of the ...

with a personal attack on the SPD lead candidate

Willy Brandt

Willy Brandt (; born Herbert Ernst Karl Frahm; 18 December 1913 – 8 October 1992) was a German politician and statesman who was leader of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) from 1964 to 1987 and concurrently served as the Chancellor ...

, Lord Mayor of West-Berlin, saying that Brandt's illegitimate birth had disqualified him from holding any sort of office. After failing to keep their majority in the general election on 17 September, the CDU/CSU again needed to include the FDP in a coalition government. Adenauer was forced to make two concessions: to relinquish the chancellorship before the end of the new term, his fourth, and to replace his foreign minister. In his last years in office, Adenauer used to take a nap after lunch and, when he was traveling abroad and had a public function to attend, he sometimes asked for a bed in a room close to where he was supposed to be speaking, so that he could rest briefly before he appeared.

John Gunther

John Gunther (August 30, 1901 – May 29, 1970) was an Americans, American journalist and writer.

His success came primarily by a series of popular sociopolitical works, known as the "Inside" books (1936–1972), including the best-sell ...

: ''Inside Europe Today'', Harper and Brothers, New York, 1961; Library of Congress catalog card number: 61-9706

During this time, Adenauer came into conflict with the Economics Minister

Ludwig Erhard