1978 smallpox outbreak in the United Kingdom on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The 1978 smallpox outbreak in the United Kingdom resulted in the death of Janet Parker, a British medical photographer, who became the last recorded person to die from

The 1978 smallpox outbreak in the United Kingdom resulted in the death of Janet Parker, a British medical photographer, who became the last recorded person to die from

Special disease control measures had to be put into place for Parker's funeral. Ron Fleet from

Special disease control measures had to be put into place for Parker's funeral. Ron Fleet from

An official government inquiry into Parker's death was conducted by a panel led by microbiologist R.A. Shooter, and comprising Dr

An official government inquiry into Parker's death was conducted by a panel led by microbiologist R.A. Shooter, and comprising Dr  The inquiry's report noted that Bedson had failed to inform the authorities of changes in his research that could have affected safety. Shooter's enquiry discovered that the Dangerous Pathogens Advisory Group had inspected the laboratory on two occasions and each time recommended that the smallpox research be continued there, even though the facilities at the laboratory fell far short of those required by law. Several of the staff at the laboratory had received no special training. Inspectors from the WHO had told Bedson that the physical facilities at the laboratory did not meet WHO standards, but had nonetheless only recommended a few changes in laboratory procedures. Bedson misled the WHO about the volume of work handled by the laboratory, telling them that it had progressively declined since 1973, when in fact it had risen substantially as Bedson tried to finish his work before the laboratory closed. Shooter also found that while Parker had been vaccinated, it had not been done recently enough to protect her against smallpox. A foreword by the Secretary of State for Social Services, Patrick Jenkin, noted that the University of Birmingham disputed the report's findings.

The report concluded that Parker had been infected by a strain of smallpox virus called Abid (named after the three-year-old Pakistani boy from whom it had originally been isolated), which was being handled in the smallpox laboratory during 24–25 July 1978. It found that there was "no doubt" that Parker had been infected at her workplace, and identified three possible ways in which this could have occurred: air current transmission; personal contact; or contact with contaminated apparatus. The report favoured air current transmission and concluded that the virus could have travelled in air currents up a service duct from the laboratory below to a room in the Anatomy Department that was used for telephone calls. On 25 July, Parker had spent much more time there than usual ordering photographic materials because the financial year was about to end.

Since Shooter's Report potentially played an important role in the

The inquiry's report noted that Bedson had failed to inform the authorities of changes in his research that could have affected safety. Shooter's enquiry discovered that the Dangerous Pathogens Advisory Group had inspected the laboratory on two occasions and each time recommended that the smallpox research be continued there, even though the facilities at the laboratory fell far short of those required by law. Several of the staff at the laboratory had received no special training. Inspectors from the WHO had told Bedson that the physical facilities at the laboratory did not meet WHO standards, but had nonetheless only recommended a few changes in laboratory procedures. Bedson misled the WHO about the volume of work handled by the laboratory, telling them that it had progressively declined since 1973, when in fact it had risen substantially as Bedson tried to finish his work before the laboratory closed. Shooter also found that while Parker had been vaccinated, it had not been done recently enough to protect her against smallpox. A foreword by the Secretary of State for Social Services, Patrick Jenkin, noted that the University of Birmingham disputed the report's findings.

The report concluded that Parker had been infected by a strain of smallpox virus called Abid (named after the three-year-old Pakistani boy from whom it had originally been isolated), which was being handled in the smallpox laboratory during 24–25 July 1978. It found that there was "no doubt" that Parker had been infected at her workplace, and identified three possible ways in which this could have occurred: air current transmission; personal contact; or contact with contaminated apparatus. The report favoured air current transmission and concluded that the virus could have travelled in air currents up a service duct from the laboratory below to a room in the Anatomy Department that was used for telephone calls. On 25 July, Parker had spent much more time there than usual ordering photographic materials because the financial year was about to end.

Since Shooter's Report potentially played an important role in the

(online)

* * *{{cite news , url = http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F40714F6395511728DDDAD0894DA405B898BF1D3 , author = Stockton, William , title = Smallpox is not dead , work =

The Lonely Death of Janet Parker

, Birmingham Live * Portrait photograph (pre-1978) of Janet Parke

(online)

*1978 newspaper article ''Smallpox virus escapes'

(online)

*1978 newspaper article about Janet Parker's father being taken into quarantin

(online)

*1978 newspaper article about Janet Parker's mother being released from quarantin

(online)

Smallpox outbreak Smallpox outbreak, 1978 Smallpox outbreak in the United Kingdom, 1978 Smallpox outbreak Smallpox outbreak Deaths from smallpox Deaths from laboratory accidents Health in Birmingham, West Midlands Infectious disease deaths in England Smallpox eradication United Kingdom, 1978 ar:جانيت باركر da:Janet Parker de:Janet Parker es:Janet Parker nl:Janet Parker ja:ジャネット・パーカー pl:Janet Parker pt:Janet Parker

The 1978 smallpox outbreak in the United Kingdom resulted in the death of Janet Parker, a British medical photographer, who became the last recorded person to die from

The 1978 smallpox outbreak in the United Kingdom resulted in the death of Janet Parker, a British medical photographer, who became the last recorded person to die from smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

. Her illness and death, which was connected to the deaths of two other people, led to the Shooter Inquiry, an official investigation by government-appointed experts triggering radical changes in how dangerous pathogens were studied in the UK.

The Shooter Inquiry found that Parker was accidentally exposed to a strain of smallpox virus that had been grown in a research laboratory on the floor below her workplace at the University of Birmingham Medical School

The University of Birmingham Medical School is one of Britain's largest and oldest medical schools with over 400 medical, 70 pharmacy, 140 biomedical science and 130 nursing students graduating each year. It is based at the University of Birmi ...

. Shooter concluded that the mode of transmission was most likely airborne through a poorly maintained service duct between the two floors. However, this assertion has been subsequently challenged, including when the University of Birmingham

The University of Birmingham (informally Birmingham University) is a Public university, public research university located in Edgbaston, Birmingham, United Kingdom. It received its royal charter in 1900 as a successor to Queen's College, Birmingha ...

was acquitted following a prosecution for breach of Health and Safety legislation connected with Parker's death. Several internationally recognised experts produced evidence during the prosecution to show that it was unlikely that Parker was infected by airborne transmission in this way. Although there is general agreement that the source of Parker's infection was the smallpox virus grown at the Medical School laboratory, how Parker contracted the disease remains unknown.

Background

Smallpox research at the Birmingham Medical School

Smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

is an infectious disease

An infection is the invasion of tissues by pathogens, their multiplication, and the reaction of host tissues to the infectious agent and the toxins they produce. An infectious disease, also known as a transmissible disease or communicable di ...

unique to humans, caused by either of two virus

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea.

Since Dmitri Ivanovsk ...

variants named ''Variola major'' and ''Variola minor''. The World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for international public health. The WHO Constitution states its main objective as "the attainment by all peoples of the highest possible level of ...

(WHO) had established a smallpox eradication programme and, by 1978, was close to declaring that the disease had been eradicated globally. The last naturally occurring infection was of ''Variola minor'' in Somalia

Somalia, , Osmanya script: 𐒈𐒝𐒑𐒛𐒐𐒘𐒕𐒖; ar, الصومال, aṣ-Ṣūmāl officially the Federal Republic of SomaliaThe ''Federal Republic of Somalia'' is the country's name per Article 1 of thProvisional Constituti ...

in 1977.

At the time of the 1978 outbreak, a laboratory at University of Birmingham Medical School

The University of Birmingham Medical School is one of Britain's largest and oldest medical schools with over 400 medical, 70 pharmacy, 140 biomedical science and 130 nursing students graduating each year. It is based at the University of Birmi ...

had been conducting research on variants of smallpox virus known as "whitepox viruses", which were considered to be a threat to the success of the WHO's eradication programme. The laboratory was part of the Microbiology Department, the head of which was virologist Henry Bedson

Henry Samuel Bedson, MD, MRCP (29 September 1929 – 6 September 1978), was a British virologist and head of the Department of Medical Microbiology at Birmingham Medical School, where his research focused on smallpox and monkeypox. He was ...

, son of Sir Samuel Phillips Bedson.

A smallpox outbreak in the area had occurred in 1966, when Tony McLennan, a medical photographer working at the medical school, contracted the disease. He had a mild form of the disease, which was not diagnosed for eight weeks. He was not quarantined and there were at least twelve further cases in the West Midlands

West or Occident is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from east and is the direction in which the Sun sets on the Earth.

Etymology

The word "west" is a Germanic word passed into some ...

, five of whom were quarantined in Witton Isolation Hospital

Witton Isolation Hospital was a facility for the treatment and quarantine of smallpox victims and their contacts in Birmingham, England, from 1894 to 1966.

History Operation

Built in 1894, Witton Isolation Hospital was initially in a semi-rural ...

in Birmingham. There are no records of any formal enquiries on the source of this outbreak despite concerns expressed by the then head of the laboratory, Peter Wildy

Norman Peter Leete Wildy (31 March 1920 – 10 March 1987) was a 20th-century British virologist who was an expert on the herpes simplex virus.

Education and personal life

He was born in Tunbridge Wells in Kent on 31 March 1920 the son of Eric ...

.

In 1977, the World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for international public health. The WHO Constitution states its main objective as "the attainment by all peoples of the highest possible level of ...

(WHO) had told Henry Bedson that his application for his laboratory to become a Smallpox Collaborating Centre had been rejected. This was partly because of safety concerns; the WHO wanted as few laboratories as possible handling the virus.

Janet Parker

Parker was born in March 1938, and was the only daughter of Frederick and Hilda Witcomb (née Linscott). She was married to Joseph Parker, a Post Office engineer, and lived in Burford Park Road,Kings Norton

Kings Norton, alternatively King's Norton, is an area of Birmingham, England. Historic counties of England, Historically in Worcestershire, it was also a Birmingham City Council ward (politics), ward within the Government of Birmingham, Engl ...

, Birmingham, UK. After several years as a police photographer she joined the University of Birmingham Medical School

The University of Birmingham Medical School is one of Britain's largest and oldest medical schools with over 400 medical, 70 pharmacy, 140 biomedical science and 130 nursing students graduating each year. It is based at the University of Birmi ...

, where she was employed as a medical photographer in the Anatomy Department. Parker often worked in a darkroom above the laboratory where research on smallpox viruses was being conducted.

The infection and related events

Parker's illness and death

On 11 August 1978, Parker (who had been vaccinated against smallpox in 1966, but not since) fell ill; she had a headache and pains in her muscles. She developed spots that were thought to be a benign rash, or chickenpox. On 20 August at 3pm, she was admitted to East Birmingham (now Heartlands) Hospital and a clinical diagnosis of ''Variola major'', the most serious type of smallpox, was made by consultant Alasdair Geddes. By this time the rash had spread and covered all Parker's body, including the palms of her hands and soles of her feet, and it was confluent on her face. At 10pm she was on her way toCatherine-de-Barnes Isolation Hospital

Catherine-de-Barnes Isolation Hospital was a specialist isolation hospital for infection control in Catherine-de-Barnes, a village within the Metropolitan Borough of Solihull in the English county of West Midlands.

Foundation

In 1907, a "fever h ...

near Solihull

Solihull (, or ) is a market town and the administrative centre of the wider Metropolitan Borough of Solihull in West Midlands County, England. The town had a population of 126,577 at the 2021 Census. Solihull is situated on the River Blyth ...

. By 11pm all her close contacts, including her parents, were placed in quarantine. Her parents were later also transferred to Catherine-de-Barnes. The next day, poxvirus infection was confirmed by Henry Bedson, then Head of the Smallpox laboratory at the Medical School, by electron microscopy of vesicle fluid, which Geddes had sampled from Parker's rash. (Samples of the fluid were also collected by a biomedical scientist for examination at the Regional Virus Laboratory, which was in East Birmingham Hospital). Parker died of smallpox at Catherine-de-Barnes on 11 September 1978. She was the last recorded person to die from smallpox.

Special disease control measures had to be put into place for Parker's funeral. Ron Fleet from

Special disease control measures had to be put into place for Parker's funeral. Ron Fleet from Sheldon Sheldon may refer to:

* Sheldon (name), a given name and a surname, and a list of people with the name

Places Australia

* Sheldon, Queensland

*Sheldon Forest, New South Wales

United Kingdom

*Sheldon, Derbyshire, England

*Sheldon, Devon, England

* ...

, who at the time of Parker's death worked for Solihull funeral director Bastocks and later for the BBC at Pebble Mill, recalled that he was told that authorities would not allow the body to be stored in a fridge in case the virus managed to multiply:Quoted from Brett Gibbons,

Concerns over the survival of infectious virus in Parker's body were well-founded, and at the inquest the coroner, who signed Parker's cremation certificate, disallowed an autopsy for safety reasons.

Quarantine and containment

Many people had close contact with Parker before she was admitted to hospital. The outbreak prevention response included 260 people being immediately quarantined, several of them at Catherine-de-Barnes Hospital, including the ambulance driver who transported Parker. Over 500 people who had been (or had possibly been) in contact with Parker were given vaccinations against smallpox. On 26 August, health officials went to Parker's house in Burford Park Road, Kings Norton, and fumigated her home and car. On 28 August, five hundred people were placed in quarantine in their homes for two weeks. Parker's mother contracted smallpox on 7 September, despite having been vaccinated against the disease on 24 August. Her case was described as "very minor" and she was subsequently declared free from infection and was discharged from hospital on 22 September. Other than Parker's mother, no further cases occurred. The other close contacts, which included twobiomedical scientist A biomedical scientist is a scientist trained in biology, particularly in the context of medical laboratory sciences or laboratory medicine. These scientists work to gain knowledge on the main principles of how the human body works and to find new w ...

s from the Regional Virus Laboratory, were released from quarantine in Catherine-de-Barnes on 10 October 1978.

Birmingham was declared officially free of smallpox on 16 October 1978. Over a year later, in October 1979, the university authorities fumigated the Medical School East Wing. The ward at Catherine-de-Barnes Hospital in which Parker had died was still sealed off five years after her death, all the furniture and equipment inside left untouched.

Related deaths

On 5 September 1978, Parker's 71-year-old father, Frederick Witcomb, of Myrtle Avenue,Kings Heath

Kings Heath (historically, and still occasionally King's Heath) is a suburb of south Birmingham, England, four miles south of the city centre. Historically in Worcestershire, it is the next suburb south from Moseley on the A435, Alcester road. ...

, died while in quarantine at Catherine-de-Barnes Hospital. He appeared to have died following a cardiac arrest when visiting his daughter. No post-mortem was carried out on his body because of the risk of smallpox infection.

On 6 September 1978, Henry Bedson, head of the Birmingham Medical School microbiology department, committed suicide while in quarantine at his home in Cockthorpe Close, Harborne

Harborne is an area of south-west Birmingham, England. It is one of the most affluent areas of the Midlands, southwest from Birmingham city centre. It is a Birmingham City Council ward in the formal district and in the parliamentary constitu ...

. He cut his throat in the garden shed and died at Birmingham Accident Hospital

Birmingham Accident Hospital, formerly known as Birmingham Accident Hospital and Rehabilitation Centre, was established in April 1941 as Birmingham's response to two reports, the British Medical Association's Committee on Fractures (1935) and th ...

a few days later. His suicide note read:' In Bedson's Munk's Roll

The Roll of the Royal College of Physicians of London, commonly referred to as Munk's Roll, is a series of published works containing biographical entries of the fellows of the Royal College of Physicians. It was published in print in eleven volume ...

biography published by the Royal College of Physicians

The Royal College of Physicians (RCP) is a British professional membership body dedicated to improving the practice of medicine, chiefly through the accreditation of physicians by examination. Founded by royal charter from King Henry VIII in 1 ...

, virologist Peter Wildy

Norman Peter Leete Wildy (31 March 1920 – 10 March 1987) was a 20th-century British virologist who was an expert on the herpes simplex virus.

Education and personal life

He was born in Tunbridge Wells in Kent on 31 March 1920 the son of Eric ...

and Sir Gordon Wolstenholme wrote:

Subsequent investigations and reactions

The Shooter inquiry

Christopher Booth

Sir Christopher Charles Booth (22 June 1924 – 13 July 2012) was an English clinician and medical historian, characterised as "one of the great characters of British medicine".

Booth was born in 1924 in Farnham, Surrey. His father Lionel ...

, Prof. Sir David Evans, J.R. McDonald, Dr David Tyrrell and Prof. Sir Robert Williams, with observers from the World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for international public health. The WHO Constitution states its main objective as "the attainment by all peoples of the highest possible level of ...

(WHO), The Health and Safety Executive and the Trades Union Congress

The Trades Union Congress (TUC) is a national trade union centre, a federation of trade unions in England and Wales, representing the majority of trade unions. There are 48 affiliated unions, with a total of about 5.5 million members. Frances ...

.

The inquiry's report noted that Bedson had failed to inform the authorities of changes in his research that could have affected safety. Shooter's enquiry discovered that the Dangerous Pathogens Advisory Group had inspected the laboratory on two occasions and each time recommended that the smallpox research be continued there, even though the facilities at the laboratory fell far short of those required by law. Several of the staff at the laboratory had received no special training. Inspectors from the WHO had told Bedson that the physical facilities at the laboratory did not meet WHO standards, but had nonetheless only recommended a few changes in laboratory procedures. Bedson misled the WHO about the volume of work handled by the laboratory, telling them that it had progressively declined since 1973, when in fact it had risen substantially as Bedson tried to finish his work before the laboratory closed. Shooter also found that while Parker had been vaccinated, it had not been done recently enough to protect her against smallpox. A foreword by the Secretary of State for Social Services, Patrick Jenkin, noted that the University of Birmingham disputed the report's findings.

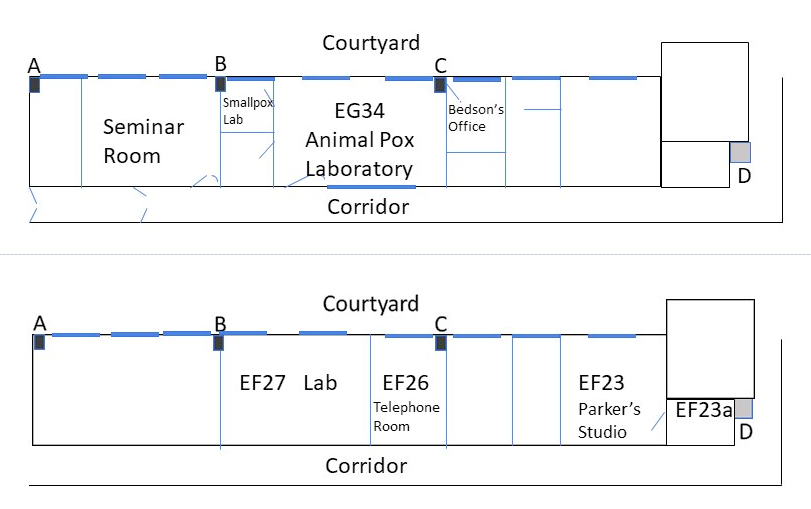

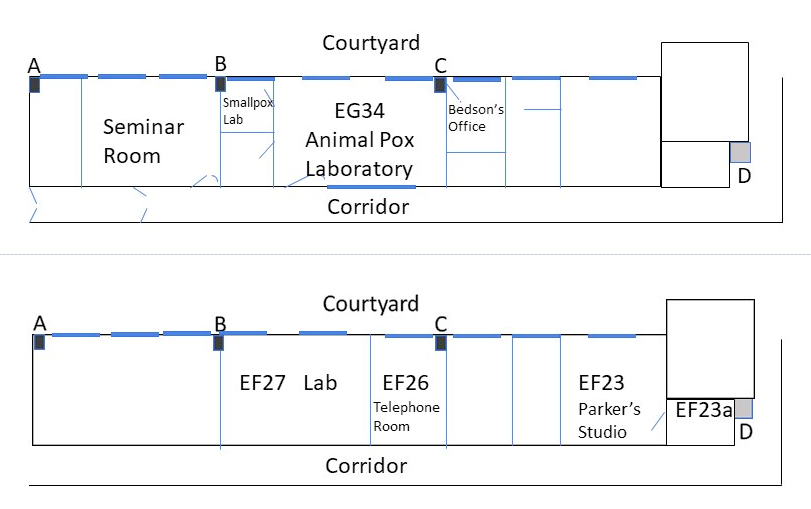

The report concluded that Parker had been infected by a strain of smallpox virus called Abid (named after the three-year-old Pakistani boy from whom it had originally been isolated), which was being handled in the smallpox laboratory during 24–25 July 1978. It found that there was "no doubt" that Parker had been infected at her workplace, and identified three possible ways in which this could have occurred: air current transmission; personal contact; or contact with contaminated apparatus. The report favoured air current transmission and concluded that the virus could have travelled in air currents up a service duct from the laboratory below to a room in the Anatomy Department that was used for telephone calls. On 25 July, Parker had spent much more time there than usual ordering photographic materials because the financial year was about to end.

Since Shooter's Report potentially played an important role in the

The inquiry's report noted that Bedson had failed to inform the authorities of changes in his research that could have affected safety. Shooter's enquiry discovered that the Dangerous Pathogens Advisory Group had inspected the laboratory on two occasions and each time recommended that the smallpox research be continued there, even though the facilities at the laboratory fell far short of those required by law. Several of the staff at the laboratory had received no special training. Inspectors from the WHO had told Bedson that the physical facilities at the laboratory did not meet WHO standards, but had nonetheless only recommended a few changes in laboratory procedures. Bedson misled the WHO about the volume of work handled by the laboratory, telling them that it had progressively declined since 1973, when in fact it had risen substantially as Bedson tried to finish his work before the laboratory closed. Shooter also found that while Parker had been vaccinated, it had not been done recently enough to protect her against smallpox. A foreword by the Secretary of State for Social Services, Patrick Jenkin, noted that the University of Birmingham disputed the report's findings.

The report concluded that Parker had been infected by a strain of smallpox virus called Abid (named after the three-year-old Pakistani boy from whom it had originally been isolated), which was being handled in the smallpox laboratory during 24–25 July 1978. It found that there was "no doubt" that Parker had been infected at her workplace, and identified three possible ways in which this could have occurred: air current transmission; personal contact; or contact with contaminated apparatus. The report favoured air current transmission and concluded that the virus could have travelled in air currents up a service duct from the laboratory below to a room in the Anatomy Department that was used for telephone calls. On 25 July, Parker had spent much more time there than usual ordering photographic materials because the financial year was about to end.

Since Shooter's Report potentially played an important role in the court case

A legal case is in a general sense a dispute between opposing parties which may be resolved by a court, or by some equivalent legal process. A legal case is typically based on either civil or criminal law. In most legal cases there are one or mor ...

against the university for breach of safety legislation, its official publication was postponed until the outcome of the trial was known, and it was not published until 1980.

Once it was published it had a significant impact. Shooter's report was debated by Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

. Nicolas Hawkes wrote, in 1979, that:

Prosecution

On 1 December 1978 the Health and Safety Executive announced their intention to prosecute the university for breach of safety legislation. The case was heard in October 1979 atBirmingham Magistrates' Court

Birmingham ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands (county), West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1. ...

.

Although the source of infection was traced, the mode and cause of transmission was not. Evidence presented by several internationally recognised experts, including Kevin McCarthy

Kevin Owen McCarthy (born January 26, 1965) is an American politician, serving as House Minority Leader in the United States House of Representatives since 2019. A member of the Republican Party, he served as House Majority Leader under spea ...

, Allan Watt Downie and Keith R. Dumbell, showed that airborne transmission from the laboratory to the telephone room where Parker was supposedly infected was highly improbable. The experts calculated that it would require of virus fluid to have been aspirated (meaning, in this context, removed by suction of fluid and cells through a needle) and it would take 20,000 years for one particle to travel to the telephone room at the rate the fluid was aspirated. It was additionally found that although the Shooter Inquiry noted the poor state of the duct sealing in the laboratory, this was caused after the outbreak by engineers fumigating the laboratory and ducts. The university was found not guilty of causing Parker's death.

Other litigation

In August 1981, following a formal claim for damages made by the trade unionAssociation of Scientific, Technical and Managerial Staffs

The Association of Scientific, Technical and Managerial Staffs (ASTMS) was a British trade union which existed between 1969 and 1988.

History

The ASTMS was created in 1969 when ASSET (the Association of Supervisory Staffs, Executives and Techni ...

in 1979, Parker's husband, Joseph, was awarded £25,000 in compensation.

Conclusions and impact

Although it seems clear that the source of Parker's infection was the smallpox virus grown at the University of Birmingham Medical School laboratory, it remains unknown how Parker came to be infected. Shooter's criticisms of the laboratory's procedures triggered radical changes in how dangerous pathogens were studied in the UK,, but the inquiry's conclusions on the transmission of the virus have not been generally accepted. Professor Mark Pallen, who wrote a book about the case, says that the air duct theory "was not really believed by anyone in the know". Brian Escott-Cox QC, who successfully defended the university in the subsequent prosecution, said in 2018: In light of this incident, all known stocks of smallpox were destroyed or transferred to one of two WHO reference laboratories which had BSL-4 facilities: theCenters for Disease Control and Prevention

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is the national public health agency of the United States. It is a United States federal agency, under the Department of Health and Human Services, and is headquartered in Atlanta, Georgi ...

(CDC) in the United States and the State Research Center of Virology and Biotechnology VECTOR

The State Research Center of Virology and Biotechnology VECTOR, also known as the Vector Institute (russian: Государственный научный центр вирусологии и биотехнологии „Вектор“, Gosu ...

in Koltsovo, Russia.

At the time of the outbreak, the WHO had been about to certify that smallpox had been eradicated globally. It eventually did so in 1980.

See also

*Rahima Banu

Rahima Banu Begum ( bn, রহিমা বানু বেগম; born 16 October 1972) is the last known person to have been infected with naturally occurring ''Variola major'' smallpox, the more deadly variety of the disease.

Biography

...

, last person infected with naturally occurring ''Variola major''

* Ali Maow Maalin

Ali Maow Maalin ( so, Cali Macow Macallin; also Mao Moallim and Mao' Mo'allim; 1954 – 22 July 2013) was a Somali hospital cook and health worker from Merca who is the last person known to have been infected with naturally occurring '' Variola ...

, last person infected with naturally occurring ''Variola minor''

* List of unusual deaths

This list of unusual deaths includes unique or extremely rare circumstances of death recorded throughout history, noted as being unusual by multiple sources.

Antiquity

Middle Ages

Renaissance

Early modern period

19th centur ...

References

Bibliography

* * Jonathan B. Tucker, ''Scourge: The Once and Future Threat of Smallpox'' (Grove Press) 2002(online)

* * *{{cite news , url = http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F40714F6395511728DDDAD0894DA405B898BF1D3 , author = Stockton, William , title = Smallpox is not dead , work =

The New York Times Magazine

''The New York Times Magazine'' is an American Sunday magazine supplement included with the Sunday edition of ''The New York Times''. It features articles longer than those typically in the newspaper and has attracted many notable contributors. ...

, date = 4 February 1979

External links

*The Lonely Death of Janet Parker

, Birmingham Live * Portrait photograph (pre-1978) of Janet Parke

(online)

*1978 newspaper article ''Smallpox virus escapes'

(online)

*1978 newspaper article about Janet Parker's father being taken into quarantin

(online)

*1978 newspaper article about Janet Parker's mother being released from quarantin

(online)

Smallpox outbreak Smallpox outbreak, 1978 Smallpox outbreak in the United Kingdom, 1978 Smallpox outbreak Smallpox outbreak Deaths from smallpox Deaths from laboratory accidents Health in Birmingham, West Midlands Infectious disease deaths in England Smallpox eradication United Kingdom, 1978 ar:جانيت باركر da:Janet Parker de:Janet Parker es:Janet Parker nl:Janet Parker ja:ジャネット・パーカー pl:Janet Parker pt:Janet Parker