1924 Italian general election on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

General elections were held in

While Mussolini appointed an economic liberal minister to the economy, this changed as the

While Mussolini appointed an economic liberal minister to the economy, this changed as the

Read online, registration required

/ref> On 3 January 1925, Mussolini made a truculent speech before the

Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

on 6 April 1924 to elect the members of the Chamber of Deputies

The chamber of deputies is the lower house in many bicameral legislatures and the sole house in some unicameral legislatures.

Description

Historically, French Chamber of Deputies was the lower house of the French Parliament during the Bourb ...

.Dieter Nohlen

Dieter Nohlen (born 6 November 1939) is a German academic and political scientist. He currently holds the position of Emeritus Professor of Political Science in the Faculty of Economic and Social Sciences of the University of Heidelberg. An ex ...

& Philip Stöver (2010) ''Elections in Europe: A data handbook'', p1047 They were held two years after the March on Rome

The March on Rome () was an organized mass demonstration in October 1922 which resulted in Benito Mussolini's National Fascist Party (, PNF) ascending to power in the Kingdom of Italy. In late October 1922, Fascist Party leaders planned a march ...

, in which Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

's National Fascist Party

The National Fascist Party (, PNF) was a political party in Italy, created by Benito Mussolini as the political expression of Italian fascism and as a reorganisation of the previous Italian Fasces of Combat. The party ruled the Kingdom of It ...

rose to power, and under the controversial Acerbo Law, which stated that the party with the largest share of the votes would automatically receive two-thirds of the seats in Parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

as long as they received over 25% of the vote.Nohlen & Stöver, p.1033

Mussolini's National List (an alliance of fascists and a few liberal political parties) used intimidation tactics against voters, resulting in a landslide victory and a subsequent two-thirds majority

A supermajority is a requirement for a proposal to gain a specified level of support which is greater than the threshold of one-half used for a simple majority. Supermajority rules in a democracy can help to prevent a majority from eroding fund ...

. This was the country's last multi-party

In political science, a multi-party system is a political system where more than two meaningfully-distinct political parties regularly run for office and win elections. Multi-party systems tend to be more common in countries using proportional r ...

election until the 1946 Italian general election.

Background

On 22 October 1922Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

, the leader of the National Fascist Party

The National Fascist Party (, PNF) was a political party in Italy, created by Benito Mussolini as the political expression of Italian fascism and as a reorganisation of the previous Italian Fasces of Combat. The party ruled the Kingdom of It ...

, attempted a coup d'état

A coup d'état (; ; ), or simply a coup

, is typically an illegal and overt attempt by a military organization or other government elites to unseat an incumbent leadership. A self-coup is said to take place when a leader, having come to powe ...

(titled by the Fascist propaganda as the March on Rome

The March on Rome () was an organized mass demonstration in October 1922 which resulted in Benito Mussolini's National Fascist Party (, PNF) ascending to power in the Kingdom of Italy. In late October 1922, Fascist Party leaders planned a march ...

) in which around 30,000 Italian fascists

Italian fascism (), also called classical fascism and Fascism, is the original fascist ideology, which Giovanni Gentile and Benito Mussolini developed in Italy. The ideology of Italian fascism is associated with a series of political parties le ...

took part. The '' quadrumvirs'' leading the Fascist party, General Emilio De Bono, Italo Balbo

Italo Balbo (6 June 1896 – 28 June 1940) was an Fascist Italy (1922–1943), Italian fascist politician and Blackshirts' leader who served as Italy's Marshal of the Air Force, Governor-General of Italian Libya and Commander-in-Chief of Italian ...

(one of the most famous ''ras''), Michele Bianchi

Michele Bianchi (22 July 1883 – 3 February 1930) was an Italian revolutionary syndicalist leader who took a position in the Unione Italiana del Lavoro (UIL). He was among the founding members of the Fascist movement. He was widely seen as ...

, and Cesare Maria de Vecchi, organized the march while Mussolini stayed behind for most of the march; Mussolini allowed pictures to be taken of him marching along with the Fascist marchers. Generals Gustavo Fara and Sante Ceccherini assisted to the preparations of the March of 18 October. Other organizers of the march included the Marquis Dino Perrone Compagni and Ulisse Igliori.

On 24 October 1922 Mussolini declared before 60,000 people at the Fascist Congress in Naples

Naples ( ; ; ) is the Regions of Italy, regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 908,082 within the city's administrative limits as of 2025, while its Metropolitan City of N ...

: "Our program is simple: we want to rule Italy." The Blackshirts

The Voluntary Militia for National Security (, MVSN), commonly called the Blackshirts (, CCNN, singular: ) or (singular: ), was originally the paramilitary wing of the National Fascist Party, known as the Squadrismo, and after 1923 an all-vo ...

occupied some strategic points of the country and began to move on the capital. On 26 October, former Prime Minister of Italy

The prime minister of Italy, officially the president of the Council of Ministers (), is the head of government of the Italy, Italian Republic. The office of president of the Council of Ministers is established by articles 92–96 of the Co ...

, Antonio Salandra

Antonio Salandra (; 13 August 1853 – 9 December 1931) was a conservative Italian politician, journalist, and writer who served as the 21st prime minister of Italy between 1914 and 1916. He ensured the entry of Italy in World War I on the side o ...

, warned the incumbent Prime Minister Luigi Facta that Mussolini was demanding his resignation and that he was preparing to march on Rome. Facta did not believe Salandra and thought that Mussolini would govern quietly at his side. To meet the threat posed by the bands of Fascist troops now gathering outside Rome, Facta (who had resigned but continued to hold power) ordered a state of siege

''State of Siege'' () is a 1972 French–Italian–West German political thriller film directed by Costa-Gavras starring Yves Montand and Renato Salvatori. The story is based on an actual incident in 1970, when U.S. official Dan Mitrione was k ...

for Rome. Having had previous conversations with King Victor Emmanuel III

Victor Emmanuel III (; 11 November 1869 – 28 December 1947) was King of Italy from 29 July 1900 until his abdication on 9 May 1946. A member of the House of Savoy, he also reigned as Emperor of Ethiopia from 1936 to 1941 and King of the Albania ...

about the repression of Fascist violence, he was sure the King would agree. Instead, the King refused to sign the military order. On 28 October, the King handed power to Mussolini, who was supported by the military, the business class, and political right.

While the march itself was composed of fewer than 30,000 men, the King feared a civil war as he did not consider the Facta's government strong enough, and Fascism was no longer seen as a threat to the establishment. Mussolini was asked to form his cabinet on 29 October while some 25,000 Blackshirts were parading in Rome. The March on Rome was not the conquest of power which Fascism later celebrated but rather the precipitating force behind a transfer of power within the framework of the constitution. This transition was made possible by the surrender of public authorities in the face of Fascist intimidation. Many business and financial leaders believed it would be possible to manipulate Mussolini, whose early speeches and policies emphasized free market

In economics, a free market is an economic market (economics), system in which the prices of goods and services are determined by supply and demand expressed by sellers and buyers. Such markets, as modeled, operate without the intervention of ...

and ''laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( , from , ) is a type of economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies or regulations). As a system of thought, ''laissez-faire'' ...

'' economics.

While Mussolini appointed an economic liberal minister to the economy, this changed as the

While Mussolini appointed an economic liberal minister to the economy, this changed as the Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

affected Italy along with the rest of the world starting in 1929, and Mussolini responded to it by increasing the role of the state in the economy to avoid a banking crisis. Back in October 1922, even though the coup failed in giving power directly to the Fascist party, it nonetheless resulted in a parallel agreement between Mussolini and the King that made Mussolini the head of the Italian government. A few weeks after the election, Giacomo Matteotti

Giacomo Matteotti (; 22 May 1885 – 10 June 1924) was an Italian socialist politician and secretary of the Unitary Socialist Party (PSU). He was elected deputy of the Chamber of Deputies three times, in 1919, 1921 and in 1924. On 30 May 19 ...

, the leader of the Unitary Socialist Party, requested during his speech in front of the Parliament that the elections be annulled because of the irregularities. On June 10, Matteotti was assassinated by the Blackshirts and his murder provoked a momentary crisis in the Mussolini government. The opposition parties responded weakly or were generally unresponsive. Many of the socialists, liberals, and moderates boycotted Parliament in the Aventine Secession, hoping to force the King to dismiss Mussolini.

On 31 December 1924 Blackshirt leaders met with Mussolini and gave him an ultimatum—crush the opposition or they would do so without him. Fearing a revolt by his own militants, he decided to drop all trappings of democracy. Read online, registration required

/ref> On 3 January 1925, Mussolini made a truculent speech before the

Chamber of Deputies

The chamber of deputies is the lower house in many bicameral legislatures and the sole house in some unicameral legislatures.

Description

Historically, French Chamber of Deputies was the lower house of the French Parliament during the Bourb ...

in which he took responsibility for '' squadristi'' violence but did not mention the assassination of Matteotti. This speech usually is taken as the beginning of the Fascist dictatorship because it was followed by several laws restricting or canceling common democratic liberties, all rubber-stamped by a Fascist-controlled Parliament.

Electoral system

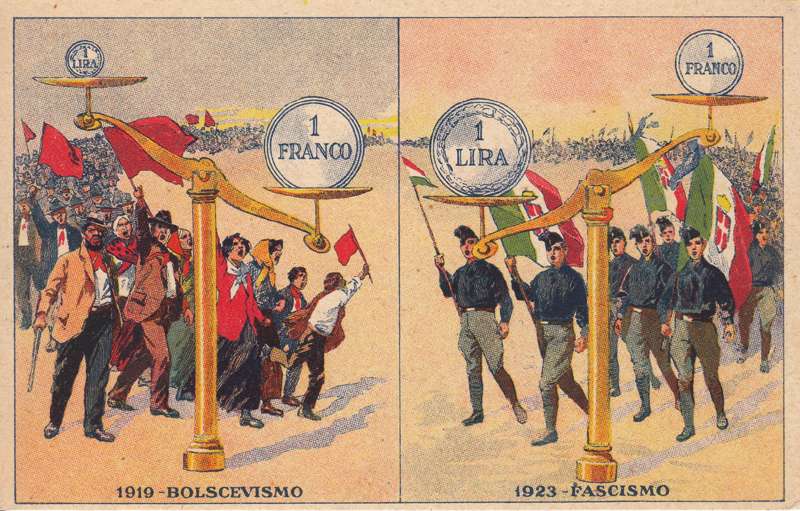

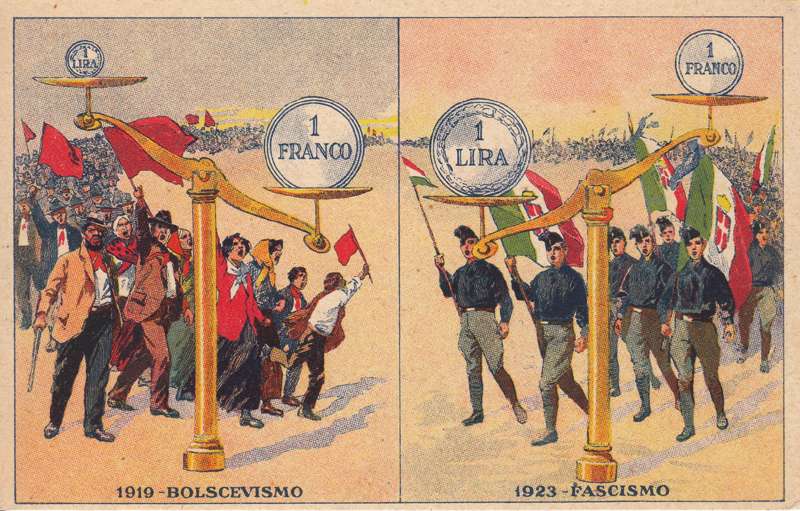

This was the first and only multi-party general election held under the terms of the Acerbo Law. The Acerbo Law had been adopted by Parliament in November 1923 and stated that the party gaining the largest share of the votes—provided they had gained at least 25 percent of the votes—gained two-thirds of the seats in parliament. The remaining third was shared amongst the other parties throughproportional representation

Proportional representation (PR) refers to any electoral system under which subgroups of an electorate are reflected proportionately in the elected body. The concept applies mainly to political divisions (Political party, political parties) amon ...

.

Parliamentary parties and leaders

Results

By region

References

{{Italian elections General elections in ItalyGeneral

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air force, air and space forces, marines or naval infantry.

In some usages, the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colone ...

Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

Italian fascism