1880s on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The 1880s (pronounced "eighteen-eighties") was the

The 1880s (pronounced "eighteen-eighties") was the

, Hungarian Patent Office, January 29, 2004. Bláthy had suggested the use of closed-cores, Zipernowsky the use of shunt connections, and Déri had performed the experiments.Smil, Vaclav, ''Creating the Twentieth Century: Technical Innovations of 1867—1914 and Their Lasting Impact''

Oxford University Press, 2005, p. 71. Electrical and electronic systems the world over continue to rely on the principles of the original Z.B.D. transformers. The inventors also popularized the word "transformer" to describe a device for altering the EMF of an electric current, although the term had already been in use by 1882. *1884–1885: *1885–1888:

*1885–1888:

Heinrich Rudolf Hertz

''". Biographies of Famous Electrochemists and Physicists Contributed to Understanding of Electricity, Biosensors & Bioelectronics. *1888–1890: Isaac Peral of

Woodbank Communications Ltd.'s Electropaedia: "History of Batteries (and other things)"

*1889:

* Home Insurance Building, the first

* Home Insurance Building, the first

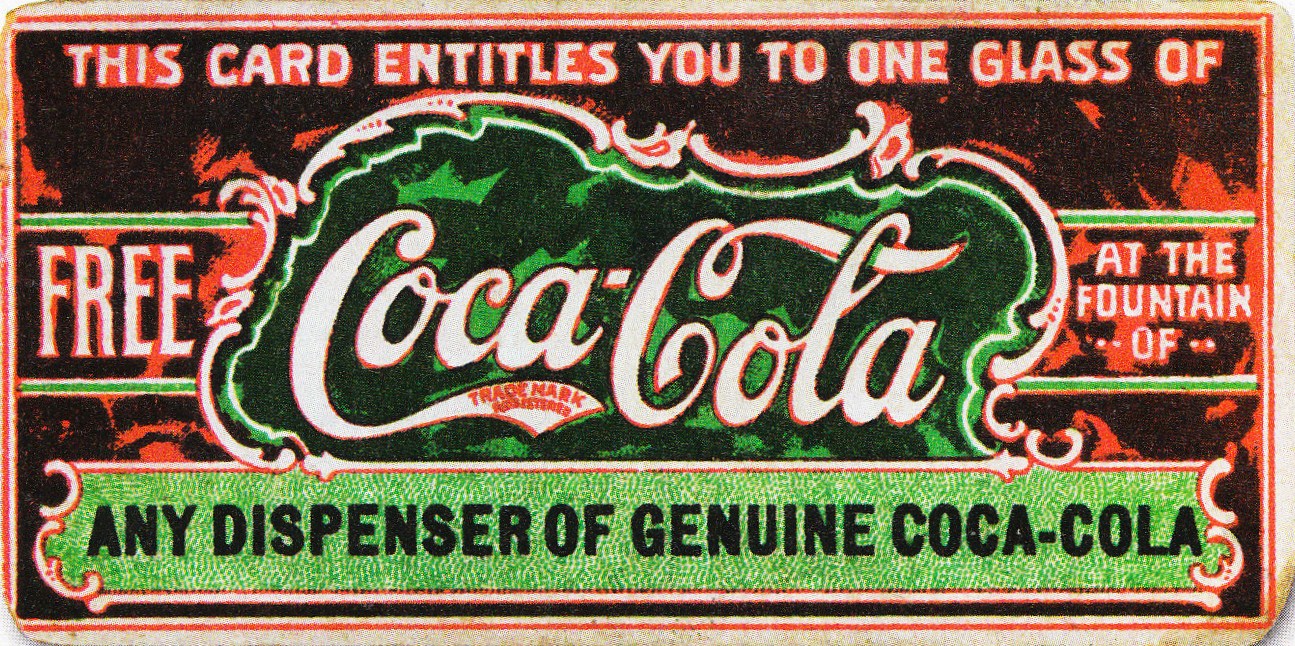

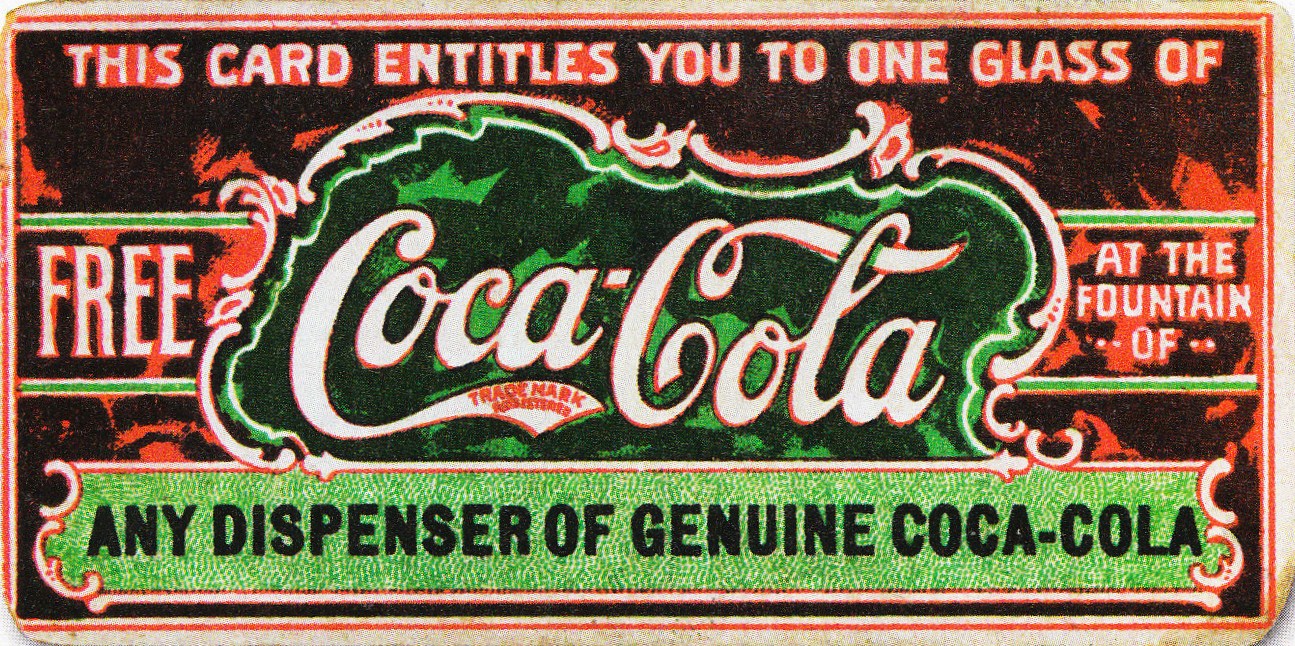

* 8 May 1886 —

* 8 May 1886 —

''The American Annual Cyclopedia and Register of Important Events of the Year'' 1881

''The American Annual Cyclopedia and Register of Important Events of the Year'' 1882

''The American Annual Cyclopedia and Register of Important Events of the Year'' 1884

''The American Annual Cyclopedia and Register of Important Events of the Year'' 1887

''The American Annual Cyclopedia and Register of Important Events of the Year'' 1888

Prices and Wages by Decade, 1880–1889

– Guide published by the University of Missouri Library points to pages in digital libraries (freely available online) that show average prices and wages by occupation, race, sex, and more. {{Authority control 1880s,

The 1880s (pronounced "eighteen-eighties") was the

The 1880s (pronounced "eighteen-eighties") was the decade

A decade (from , , ) is a period of 10 years. Decades may describe any 10-year period, such as those of a person's life, or refer to specific groupings of calendar years.

Usage

Any period of ten years is a "decade". For example, the statement ...

that began on January 1, 1880, and ended on December 31, 1889.

The period was characterized in general by economic growth and prosperity in many parts of the world, especially Europe and the Americas, with the emergence of modern cities signified by the foundation of many long-lived corporations, franchises, and brands and the introduction of the skyscraper

A skyscraper is a tall continuously habitable building having multiple floors. Most modern sources define skyscrapers as being at least or in height, though there is no universally accepted definition, other than being very tall high-rise bui ...

. The decade was a part of the Gilded Age

In History of the United States, United States history, the Gilded Age is the period from about the late 1870s to the late 1890s, which occurred between the Reconstruction era and the Progressive Era. It was named by 1920s historians after Mar ...

(1874–1907) in the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

, the Victorian Era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the reign of Queen Victoria, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. Slightly different definitions are sometimes used. The era followed the ...

in the British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

and the Belle Époque

The Belle Époque () or La Belle Époque () was a period of French and European history that began after the end of the Franco-Prussian War in 1871 and continued until the outbreak of World War I in 1914. Occurring during the era of the Fr ...

in France. It also occurred at the height of the Second Industrial Revolution

The Second Industrial Revolution, also known as the Technological Revolution, was a phase of rapid Discovery (observation), scientific discovery, standardisation, mass production and industrialisation from the late 19th century into the early ...

and saw numerous developments in science and a sudden proliferation of electrical technologies, particularly in mass transit and telecommunications.

The last living person from this decade, María Capovilla, died in 2006.

Politics and wars

Wars

*Aceh War

The Aceh War (), also known as the Dutch War or the Infidel War (1873–1904), was an armed military conflict between the Sultanate of Aceh and the Kingdom of the Netherlands which was triggered by discussions between representatives of Aceh ...

(1873–1904)

* War of the Pacific

The War of the Pacific (), also known by War of the Pacific#Etymology, multiple other names, was a war between Chile and a Treaty of Defensive Alliance (Bolivia–Peru), Bolivian–Peruvian alliance from 1879 to 1884. Fought over Atacama Desert ...

(1879–1884)

* First Boer War

The First Boer War (, ), was fought from 16 December 1880 until 23 March 1881 between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and Boers of the Transvaal (as the South African Republic was known while under British ad ...

(1880–1881)

* Mahdist War

The Mahdist War (; 1881–1899) was fought between the Mahdist Sudanese, led by Muhammad Ahmad bin Abdullah, who had proclaimed himself the "Mahdi" of Islam (the "Guided One"), and the forces of the Khedivate of Egypt, initially, and later th ...

(1881–1899)

* 1882 Anglo-Egyptian War (1882)

** 13 September 1882 — British troops occupy Cairo

Cairo ( ; , ) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Egypt and the Cairo Governorate, being home to more than 10 million people. It is also part of the List of urban agglomerations in Africa, largest urban agglomeration in Africa, L ...

, and Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

becomes a British protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a State (polity), state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over ...

.

* Sino-French War

The Sino-French or Franco-Chinese War, also known as the Tonkin War, was a limited conflict fought from August 1884 to April 1885 between the French Third Republic and Qing China for influence in Vietnam. There was no declaration of war.

The C ...

(1884–1885)

* Serbo-Bulgarian War (1885)

Internal conflicts

*American Indian Wars

The American Indian Wars, also known as the American Frontier Wars, and the Indian Wars, was a conflict initially fought by European colonization of the Americas, European colonial empires, the United States, and briefly the Confederate States o ...

(Intermittently from 1622 to 1918)

** 20 July 1881 — Sioux

The Sioux or Oceti Sakowin ( ; Dakota/ Lakota: ) are groups of Native American tribes and First Nations people from the Great Plains of North America. The Sioux have two major linguistic divisions: the Dakota and Lakota peoples (translati ...

chief Sitting Bull

Sitting Bull ( ; December 15, 1890) was a Hunkpapa Lakota people, Lakota leader who led his people during years of resistance against Federal government of the United States, United States government policies. Sitting Bull was killed by Indian ...

leads the last of his fugitive people in surrender to United States troops at Fort Buford

Fort Buford was a United States Army Post at the confluence of the Missouri and Yellowstone rivers in Dakota Territory, present day North Dakota, and the site of Sitting Bull's surrender in 1881.Ewers, John C. (1988): "When Sitting Bull Surrende ...

in Montana

Montana ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota to the east, South Dakota to the southeast, Wyoming to the south, an ...

.

* Frequent lynchings of African Americans in Southern United States

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, Dixieland, or simply the South) is List of regions of the United States, census regions defined by the United States Cens ...

during the years 1880

Events

January

*January 27 – Thomas Edison is granted a patent for the incandescent light bulb. Edison filed for a US patent for an electric lamp using "a carbon filament or strip coiled and connected ... to platina contact wires." gr ...

–1890

Events

January

* January 1 – The Kingdom of Italy establishes Eritrea as its colony in the Horn of Africa.

* January 2 – Alice Sanger becomes the first female staffer in the White House.

* January 11 – 1890 British Ultimatum: The Uni ...

* Urabi Revolt

The ʻUrabi revolt, also known as the ʻUrabi Revolution (), was a nationalist uprising in the Khedivate of Egypt from 1879 to 1882. It was led by and named for Colonel Ahmed Urabi and sought to depose the khedive, Tewfik Pasha, and end Imperia ...

(1879-1882)

Colonization

*France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

colonizes Indochina

Mainland Southeast Asia (historically known as Indochina and the Indochinese Peninsula) is the continental portion of Southeast Asia. It lies east of the Indian subcontinent and south of Mainland China and is bordered by the Indian Ocean to th ...

(1883)

* German colonization (1887)

* Increasing colonial interest and conquest in Africa leads representatives from Britain, France, Portugal, Germany, Belgium, Italy and Spain to divide Africa into regions of colonial influence at the Berlin Conference

The Berlin Conference of 1884–1885 was a meeting of colonial powers that concluded with the signing of the General Act of Berlin,

. This would be followed over the next few decades by conquest of almost the entirety of the remaining uncolonised parts of the continent, broadly along the lines determined. (1889)

Prominent political events

* 3 August 1881: ThePretoria Convention

The Pretoria Convention was the peace treaty that ended the First Boer War (16 December 1880 to 23 March 1881) between the Transvaal Boers and Great Britain. The treaty was signed in Pretoria on 3 August 1881, but was subject to ratification b ...

peace treaty is signed, officially ending the war between the Boers

Boers ( ; ; ) are the descendants of the proto Afrikaans-speaking Free Burghers of the eastern Cape frontier in Southern Africa during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. From 1652 to 1795, the Dutch East India Company controlled the Dutch ...

and Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* Great Britain, a large island comprising the countries of England, Scotland and Wales

* The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, a sovereign state in Europe comprising Great Britain and the north-eas ...

.

* 3 May 1882: The Chinese Exclusion Act

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was a United States Code, United States federal law signed by President Chester A. Arthur on May 6, 1882, prohibiting all immigration of Chinese laborers for 10 years. The law made exceptions for travelers an ...

was signed into law by President Chester A. Arthur.

*20 May 1882: Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

, Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military ...

, and Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

form The Triple Alliance as a defensive military alliance

* 1884: International Meridian Conference

The International Meridian Conference was a conference held in October 1884 in Washington, D.C., in the United States, to determine a prime meridian for international use. The conference was held at the request of President of the United State ...

in Washington D.C., held to determine the Prime Meridian of the world.

* 1884–1885: Berlin Conference

The Berlin Conference of 1884–1885 was a meeting of colonial powers that concluded with the signing of the General Act of Berlin,

, when the western powers divided Africa.

* The United States had five Presidents during the decade, the most since the 1840s. They were Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was the 19th president of the United States, serving from 1877 to 1881.

Hayes served as Cincinnati's city solicitor from 1858 to 1861. He was a staunch Abolitionism in the Un ...

, James A. Garfield, Chester A. Arthur, Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was the 22nd and 24th president of the United States, serving from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. He was the first U.S. president to serve nonconsecutive terms and the first Hist ...

and Benjamin Harrison

Benjamin Harrison (August 20, 1833March 13, 1901) was the 23rd president of the United States, serving from 1889 to 1893. He was a member of the Harrison family of Virginia—a grandson of the ninth president, William Henry Harrison, and a ...

.

* 20-22 June 1887: The Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria

The Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria was celebrated on 20 and 21 June 1887 to mark the Golden jubilee, 50th anniversary of Queen Victoria's accession on 20 June 1837. It was celebrated with a National service of thanksgiving, Thanksgiving Serv ...

was celebrated marking Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in January 1901. Her reign of 63 year ...

's 50 year reign.

* 13 May 1888: Brazil abolishes slavery, the last country in the western hemisphere

The Western Hemisphere is the half of the planet Earth that lies west of the Prime Meridian (which crosses Greenwich, London, United Kingdom) and east of the 180th meridian.- The other half is called the Eastern Hemisphere. Geopolitically, ...

to do so.

Disasters

* May to August, 1883:Krakatoa

Krakatoa (), also transcribed (), is a caldera in the Sunda Strait between the islands of Java and Sumatra in the Indonesian province of Lampung. The caldera is part of a volcanic island group (Krakatoa archipelago) comprising four islands. Tw ...

, a volcano in Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania, between the Indian Ocean, Indian and Pacific Ocean, Pacific oceans. Comprising over List of islands of Indonesia, 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, ...

, erupted cataclysmically; 36,000 people were killed, the majority being killed by the resulting tsunami

A tsunami ( ; from , ) is a series of waves in a water body caused by the displacement of a large volume of water, generally in an ocean or a large lake. Earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and underwater explosions (including detonations, ...

.

*September 1887: The Yellow river flooded and killed about 900,000 people.

*11 March to 14 March, 1888: The Great Blizzard of 1888 kills 400 in the eastern United States

The Eastern United States, often abbreviated as simply the East, is a macroregion of the United States located to the east of the Mississippi River. It includes 17–26 states and Washington, D.C., the national capital.

As of 2011, the Eastern ...

.

*May 1889: The Johnstown Flood occurred after the failure of the dam due to excessive rainfall in Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania, officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a U.S. state, state spanning the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern United States, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes region, Great Lakes regions o ...

. Nurse Clara Barton

Clarissa Harlowe Barton (December 25, 1821 – April 12, 1912) was an American nurse who founded the American Red Cross. She was a hospital nurse in the American Civil War, a teacher, and a patent clerk. Since nursing education was not then very ...

notably helped in the relief effort.

Assassinations and attempts

Prominent assassinations, targeted killings, and assassination attempts include: * 1882 - Guglielmo Oberdan fails to assassinate Austria-Hungarian EmperorFranz Joseph

Franz Joseph I or Francis Joseph I ( ; ; 18 August 1830 – 21 November 1916) was Emperor of Austria, King of Hungary, and the ruler of the Grand title of the emperor of Austria, other states of the Habsburg monarchy from 1848 until his death ...

and is executed

Science and technology

Technology

*1880:Oliver Heaviside

Oliver Heaviside ( ; 18 May 1850 – 3 February 1925) was an English mathematician and physicist who invented a new technique for solving differential equations (equivalent to the Laplace transform), independently developed vector calculus, an ...

of Camden Town

Camden Town () is an area in the London Borough of Camden, around north-northwest of Charing Cross. Historically in Middlesex, it is identified in the London Plan as one of 34 major centres in Greater London.

Laid out as a residential distri ...

, London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

, England receives a patent for the coaxial cable

Coaxial cable, or coax (pronounced ), is a type of electrical cable consisting of an inner Electrical conductor, conductor surrounded by a concentric conducting Electromagnetic shielding, shield, with the two separated by a dielectric (Insulat ...

. In 1887, Heaviside introduced the concept of loading coil

A loading coil or load coil is an inductor that is inserted into an electronic circuit to increase its inductance. The term originated in the 19th century for inductors used to prevent signal distortion in long-distance telegraph transmission c ...

s. In the 1890s, Mihajlo Idvorski Pupin would both create the loading coils and receive a patent of them, failing to credit Heaviside's work.

* 1880–1882: Development and commercial production of electric lighting was underway. Thomas Edison

Thomas Alva Edison (February11, 1847October18, 1931) was an American inventor and businessman. He developed many devices in fields such as electric power generation, mass communication, sound recording, and motion pictures. These inventions, ...

of Milan, Ohio

Milan ( ) is a village in Erie and Huron counties in the U.S. state of Ohio. The population was 1,371 at the 2020 census. It is best known as the birthplace and childhood home of Thomas Edison.

The Erie County portion of Milan is part of th ...

, established Edison Illuminating Company on December 17, 1880. Based at New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

, it was the pioneer company of the electrical power industry

Electricity is the set of physical phenomena associated with the presence and motion of matter possessing an electric charge. Electricity is related to magnetism, both being part of the phenomenon of electromagnetism, as described by Maxwel ...

. Edison's system was based on creating a central power plant equipped with electrical generator

In electricity generation, a generator, also called an ''electric generator'', ''electrical generator'', and ''electromagnetic generator'' is an electromechanical device that converts mechanical energy to electrical energy for use in an extern ...

s. Copper

Copper is a chemical element; it has symbol Cu (from Latin ) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkish-orang ...

electrical wires would then connect the station with other buildings, allowing for electric power distribution

Electric power distribution is the final stage in the Power delivery, delivery of electricity. Electricity is carried from the Electric power transmission, transmission system to individual consumers. Distribution Electrical substation, substatio ...

. Pearl Street Station

Pearl Street Station was Thomas Edison's first commercial power plant in the United States. It was located at 255–257 Pearl Street in the Financial District of Manhattan in New York City, just south of Fulton Street on a site measuring . The ...

was the first central power plant in the United States. It was located at 255–257 Pearl Street in Manhattan

Manhattan ( ) is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the Boroughs of New York City, five boroughs of New York City. Coextensive with New York County, Manhattan is the County statistics of the United States#Smallest, larg ...

on a site measuring 50 by 100 feet,"Edison" by Matthew Josephson. McGraw Hill, New York, 1959, pg. 255. , just south of Fulton Street. It began with one direct current

Direct current (DC) is one-directional electric current, flow of electric charge. An electrochemical cell is a prime example of DC power. Direct current may flow through a conductor (material), conductor such as a wire, but can also flow throug ...

generator, and it started generating electricity on September 4, 1882, serving an initial load of 400 lamps at 85 customers. By 1884, Pearl Street Station was serving 508 customers with 10,164 lamps.

*1880–1886: Charles F. Brush of Euclid, Ohio

Euclid is a city in Cuyahoga County, Ohio, United States. Located on the southern shore of Lake Erie, it is an Inner suburb, inner ring suburb of Cleveland. The population was 49,692 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, making it the fo ...

, and Brush Electric Light Company installed carbon arc lights along Broadway, New York City. A small generating station was established at Manhattan's 25th Street. The electric arc lights went into regular service on December 20, 1880. The new Brooklyn Bridge

The Brooklyn Bridge is a cable-stayed suspension bridge in New York City, spanning the East River between the boroughs of Manhattan and Brooklyn. Opened on May 24, 1883, the Brooklyn Bridge was the first fixed crossing of the East River. It w ...

of 1883 had seventy arc lamps installed in it. By 1886, there was a reported number of 1,500 arc lights installed in Manhattan.

*1880–1883: James Wimshurst of Poplar, London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

, England invents the Wimshurst Machine.

*1881–1885: Stefan Drzewiecki of Podolia

Podolia or Podillia is a historic region in Eastern Europe located in the west-central and southwestern parts of Ukraine and northeastern Moldova (i.e. northern Transnistria).

Podolia is bordered by the Dniester River and Boh River. It features ...

, Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

finishes his submarine-building project (which had begun in 1879). The crafts were constructed at Nevskiy Shipbuilding and Machinery works at Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the List of cities and towns in Russia by population, second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the Neva, River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland ...

. Altogether, 50 units were delivered to the Ministry of War. They were reportedly deployed as part of the defense of Kronstadt

Kronstadt (, ) is a Russian administrative divisions of Saint Petersburg, port city in Kronshtadtsky District of the federal cities of Russia, federal city of Saint Petersburg, located on Kotlin Island, west of Saint Petersburg, near the head ...

and Sevastopol

Sevastopol ( ), sometimes written Sebastopol, is the largest city in Crimea and a major port on the Black Sea. Due to its strategic location and the navigability of the city's harbours, Sevastopol has been an important port and naval base th ...

. In 1885, the submarines were transferred to the Imperial Russian Navy

The Imperial Russian Navy () operated as the navy of the Russian Tsardom and later the Russian Empire from 1696 to 1917. Formally established in 1696, it lasted until being dissolved in the wake of the February Revolution and the declaration of ...

. They were soon declared "ineffective" and discarded. By 1887, Drzewiecki was designing submarines for the French Third Republic

The French Third Republic (, sometimes written as ) was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 1940, after the Fall of France durin ...

.

*1881–1883: John Philip Holland

John Philip Holland (; February 24, 1841August 12, 1914) was an Irish marine engineer who developed the first submarine to be formally commissioned by the US Navy, USS Holland (SS-1) and the first Royal Navy submarine, ''Holland 1''.

Early lif ...

of Liscannor

Liscannor () is a coastal village in County Clare, Ireland. It is located between Lahinch and Doolin, close to the Cliffs of Moher. As of the 2022 census it had a population of 135.

Geography

Lying on the west coast of Ireland, on Liscan ...

, County Clare

County Clare () is a Counties of Ireland, county in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Munster in the Southern Region, Ireland, Southern part of Republic of Ireland, Ireland, bordered on the west by the Atlantic Ocean. Clare County Council ...

, Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

builds the Fenian Ram submarine for the Fenian Brotherhood

The Fenian Brotherhood () was an Irish republican organisation founded in the United States in 1858 by John O'Mahony and Michael Doheny. It was a precursor to Clan na Gael, a sister organisation to the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB). Membe ...

. During extensive trials, Holland made numerous dives and test-fired the gun using dummy projectiles. However, due to funding disputes within the Irish Republican Brotherhood

The Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB; ) was a secret oath-bound fraternal organisation dedicated to the establishment of an "independent democratic republic" in Ireland between 1858 and 1924.McGee, p. 15. Its counterpart in the United States ...

and disagreement over payments from the IRB to Holland, the IRB stole '' Fenian Ram'' and the '' Holland III'' prototype in November 1883.Davies, R. ''Nautilus: The Story of Man Under the Sea''. Naval Institute Press

The United States Naval Institute (USNI) is a private non-profit military association that offers independent, nonpartisan forums for debate of national security issues. In addition to publishing magazines and books, the Naval Institute holds se ...

. 1995. .

*1882: William Edward Ayrton

William Edward Ayrton, FRS (14 September 18478 November 1908) was an English physicist and electrical engineer.

Life

Early life and education

Ayrton was born in London, the son of Edward Nugent Ayrton, a barrister, and educated at University ...

of London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

, England and John Perry of Garvagh, County Londonderry

County Londonderry (Ulster Scots dialects, Ulster-Scots: ''Coontie Lunnonderrie''), also known as County Derry (), is one of the six Counties of Northern Ireland, counties of Northern Ireland, one of the thirty-two Counties of Ireland, count ...

, Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

build an electric tricycle

A tricycle, sometimes abbreviated to trike, is a Human-powered transport, human-powered (or gasoline or electric motor powered or assisted, or gravity powered) Three-wheeler, three-wheeled vehicle.

Some tricycles, such as cycle rickshaws (for pa ...

. It reportedly had a range of 10 to 25 miles, powered by a lead acid battery. A significant innovation of the vehicle was its use of electric light

Electric light is an artificial light source powered by electricity.

Electric Light may also refer to:

* Light fixture, a decorative enclosure for an electric light source

* Electric Light (album), ''Electric Light'' (album), a 2018 album by James ...

s, here playing the role of headlamp

A headlamp is a lamp attached to the front of a vehicle to illuminate the road ahead. Headlamps are also often called headlights, but in the most precise usage, ''headlamp'' is the term for the device itself and ''headlight'' is the term for t ...

s.

*1882: James Atkinson of Hampstead

Hampstead () is an area in London, England, which lies northwest of Charing Cross, located mainly in the London Borough of Camden, with a small part in the London Borough of Barnet. It borders Highgate and Golders Green to the north, Belsiz ...

, London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

, England invented the Atkinson cycle

The Atkinson-cycle engine is a type of internal combustion engine invented by James Atkinson (inventor), James Atkinson in 1882. The Atkinson cycle is designed to provide Energy conversion efficiency, efficiency at the expense of power density.

...

engine

An engine or motor is a machine designed to convert one or more forms of energy into mechanical energy.

Available energy sources include potential energy (e.g. energy of the Earth's gravitational field as exploited in hydroelectric power ge ...

. By use of variable engine strokes from a complex crankshaft

A crankshaft is a mechanical component used in a reciprocating engine, piston engine to convert the reciprocating motion into rotational motion. The crankshaft is a rotating Shaft (mechanical engineering), shaft containing one or more crankpins, ...

, Atkinson was able to increase the efficiency of his engine, at the cost of some power, over traditional Otto-cycle engines.

*1882: Schuyler Wheeler of Massachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode ...

invented the two-blade electric fan

A fan is a powered machine that creates airflow. A fan consists of rotating vanes or blades, generally made of wood, plastic, or metal, which act on the air. The rotating assembly of blades and hub is known as an '' impeller'', '' rotor'', or '' ...

. Henry W. Seely of New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

New York may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* ...

invented the electric safety iron

Iron is a chemical element; it has symbol Fe () and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, forming much of Earth's o ...

. Both were arguably among the earliest small domestic electrical appliances to appear.

*1882–1883: John Hopkinson

John Hopkinson, FRS, (27 July 1849 – 27 August 1898) was a British physicist, electrical engineer, Fellow of the Royal Society and President of the IEE (now the IET) twice in 1890 and 1896. He invented the three-wire (three-phase) system for ...

of Manchester

Manchester () is a city and the metropolitan borough of Greater Manchester, England. It had an estimated population of in . Greater Manchester is the third-most populous metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, with a population of 2.92&nbs ...

, England patents the three-phase electric power

Three-phase electric power (abbreviated 3ϕ) is a common type of alternating current (AC) used in electricity generation, transmission, and distribution. It is a type of polyphase system employing three wires (or four including an optional n ...

system in 1882. In 1883 Hopkinson showed mathematically that it was possible to connect two alternating current dynamos in parallel — a problem that had long bedeviled electrical engineers.

*1883: Charles Fritts, an American inventor, creates the first working solar cell

A solar cell, also known as a photovoltaic cell (PV cell), is an electronic device that converts the energy of light directly into electricity by means of the photovoltaic effect.

. The energy conversion efficiency of these early devices was less than 1%. Denounced as a fraud in the US for "generating power without consuming matter, thus violating the laws of physics

Scientific laws or laws of science are statements, based on repeated experiments or observations, that describe or predict a range of natural phenomena. The term ''law'' has diverse usage in many cases (approximate, accurate, broad, or narrow) ...

".

*1883–1885: Josiah H. L. Tuck, an American inventor, works in his own submarine designs. His 1883 model was created in Delameter Iron Works. It was 30-feet long, "all-electric and had vertical and horizontal propellers clutched to the same shaft, with a 20-feet breathing pipe and an airlock for a diver." His 1885 model, called the "Peacemaker", was larger. It used "a caustic soda

Sodium hydroxide, also known as lye and caustic soda, is an inorganic compound with the formula . It is a white solid ionic compound consisting of sodium cations and hydroxide anions .

Sodium hydroxide is a highly corrosive base and alkali t ...

patent boiler

A boiler is a closed vessel in which fluid (generally water) is heated. The fluid does not necessarily boil. The heated or vaporized fluid exits the boiler for use in various processes or heating applications, including water heating, centra ...

to power a 14-HP Westinghouse steam engine". She managed a number of short trips within the New York Harbor

New York Harbor is a bay that covers all of the Upper Bay. It is at the mouth of the Hudson River near the East River tidal estuary on the East Coast of the United States.

New York Harbor is generally synonymous with Upper New York Bay, ...

area. The Peacemaker had a submerged endurance of 5 hours. Tuck did not benefit from his achievement. His family feared that the inventor was squandering his fortune on the Peacemaker. They had him committed to an insane asylum

The lunatic asylum, insane asylum or mental asylum was an institution where people with mental illness were confined. It was an early precursor of the modern psychiatric hospital.

Modern psychiatric hospitals evolved from and eventually replace ...

by the end of the decade.

*1883–1886: John Joseph Montgomery

John Joseph Montgomery (February 15, 1858 – October 31, 1911) was an American inventor, physicist, engineer, and professor at Santa Clara University in Santa Clara, California, who is best known for his invention of controlled heavier-than-ai ...

of Yuba City, California

Yuba City ( Maidu: ''Yubu'') is a city in Northern California and the county seat of Sutter County, California

Sutter County is a county (United States), county located in the U.S. state of California. As of the 2020 United States census, ...

, starts his attempts at early flight. In 1884, using a glider designed and built in 1883, Montgomery made the "first heavier-than-air human-carrying aircraft to achieve controlled piloted flight" in the Western Hemisphere. This glider had a curved parabolic wing surface. He reportedly made a glide of "considerable length" from Otay Mesa, San Diego, California, his first successful flight and arguably the first successful one in the United States. In 1884–1885, Montgomery tested a second monoplane glider with flat wings. The innovation in design was " hinged surfaces at the rear of the wings to maintain lateral balance". These were early forms of Aileron

An aileron (French for "little wing" or "fin") is a hinged flight control surface usually forming part of the trailing edge of each wing of a fixed-wing aircraft. Ailerons are used in pairs to control the aircraft in roll (or movement aroun ...

. After experimentation with a water tank and smoke chamber to understand the nature of flow over surfaces, in 1886, Montgomery designed a third glider with fully rotating wings as pitcherons. He then turned to theoretic research towards the development of a manuscript "Soaring Flight" in 1896.

*1884–1885: On August 9, 1884, '' La France'', a French Army

The French Army, officially known as the Land Army (, , ), is the principal Army, land warfare force of France, and the largest component of the French Armed Forces; it is responsible to the Government of France, alongside the French Navy, Fren ...

airship

An airship, dirigible balloon or dirigible is a type of aerostat (lighter-than-air) aircraft that can navigate through the air flying powered aircraft, under its own power. Aerostats use buoyancy from a lifting gas that is less dense than the ...

, makes its maiden flight. Launched by Charles Renard

Charles Renard (1847–1905) born in Damblain, Vosges, was a French military engineer.

Airships

After the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871 he started work on the design of airships at the French army aeronautical department. Together with A ...

and Arthur Constantin Krebs

Arthur Constantin Krebs (16 November 1850 – 22 March 1935) was a French officer and pioneer in automotive engineering.

Life

Collaborating with Charles Renard, Krebs piloted Timeline of aviation - 19th century, the first fully control ...

. Krebs piloted the first fully controlled free-flight with the ''La France''. The long, airship, electric-powered with a 435 kg battery completed a flight that covered in 23 minutes. It was the first full round trip flight with a landing on the starting point. On its seven flights in 1884 and 1885 the ''La France'' dirigible returned five times to its starting point. "La France was the first airship that could return to its starting point in a light wind. It was long, its maximum diameter was , and it had a capacity of 66,000 cubic feet (1,869 cubic meters)." Its battery-powered motor "produced 7.5 horsepower (5.6 kilowatts). This motor was later replaced with one that produced 8.5 horsepower (6.3 kilowatts)."

*1884: Paul Gottlieb Nipkow

Paul Julius Gottlieb Nipkow (; 22 August 1860 – 24 August 1940) was a German electrical engineer and inventor. He invented the Nipkow disk, which laid the foundation of television, since his disk was a fundamental component in the first televis ...

of Lębork

Lębork (; ; ) is a town on the Łeba River, Łeba and Okalica rivers in the Gdańsk Pomerania region in northern Poland. It is the capital of Lębork County in Pomeranian Voivodeship. Its population is 37,000.

History Middle Ages

The region fo ...

, Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (, ) was a German state that existed from 1701 to 1918.Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. Rev. ed. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1946. It played a signif ...

, German Empire

The German Empire (),; ; World Book, Inc. ''The World Book dictionary, Volume 1''. World Book, Inc., 2003. p. 572. States that Deutsches Reich translates as "German Realm" and was a former official name of Germany. also referred to as Imperia ...

invents the Nipkow disk

A Nipkow disk (sometimes Anglicized as Nipkov disk; patented in 1884), also known as scanning disk, is a mechanical, rotating, geometrically operating image scanning device, patented by Paul Gottlieb Nipkow in Berlin. This scanning disk was a f ...

, an image scanning

An image scanner (often abbreviated to just scanner) is a device that optically scans images, printed text, handwriting, or an object and converts it to a digital image. The most common type of scanner used in the home and the office is the flatbe ...

device. It was the basis of his patent method of translating visual images to electronic impulses, transmit said impulses to another device and successfully reassemble the impulses to visual images. Nipkow used a selenium

Selenium is a chemical element; it has symbol (chemistry), symbol Se and atomic number 34. It has various physical appearances, including a brick-red powder, a vitreous black solid, and a grey metallic-looking form. It seldom occurs in this elem ...

photoelectric cell. Nipkow proposed and patented the first "near-practicable" electromechanical

Electromechanics combine processes and procedures drawn from electrical engineering and mechanical engineering. Electromechanics focus on the interaction of electrical and mechanical systems as a whole and how the two systems interact with each ...

television system

In Canada, a television system is a group of television stations which share common ownership, branding and programming, but which for some reason does not satisfy the criteria necessary for it to be classified as a television network under Cana ...

in 1884. Although he never built a working model of the system, Nipkow's spinning disk design became a common television image rasterizer

In computer graphics, rasterisation (British English) or rasterization (American English) is the task of taking an Digital image, image described in a vector graphics format (shapes) and converting it into a raster image (a series of pixels, dots ...

used up to 1939.

*1884: Alexander Mozhaysky

file:Mozhajskij marka SSSR 1963.jpg, Mozhaysky, identified as the "Creator of world's first airplane", on a 1963 Soviet postal stamp.

Alexander Fedorovich Mozhaysky (also transliterated as Mozhayski, Mozhayskii and Mozhayskiy; ) ( – ) was ...

of Kotka

Kotka (; ) is a town in Finland, located on the southeastern coast of the country at the mouth of the Kymi River. The population of Kotka is approximately , while the Kotka-Hamina sub-region, sub-region has a population of approximately . It is th ...

, Grand Duchy of Finland

The Grand Duchy of Finland was the predecessor state of modern Finland. It existed from 1809 to 1917 as an Autonomous region, autonomous state within the Russian Empire.

Originating in the 16th century as a titular grand duchy held by the Monarc ...

, Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

makes the second known "powered, assisted take off of a heavier-than-air craft carrying an operator". His steam-powered monoplane took off at Krasnoye Selo

Krasnoye Selo (, lit. ''Red (or beautiful) village''). Г. П. Смолицкая. "Топонимический словарь Центральной России". "Армада-Пресс", 2002 is a municipal town in Krasnos ...

, near Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the List of cities and towns in Russia by population, second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the Neva, River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland ...

, making a hop and "covering between 65 and 100 feet". The monoplane had a failed landing

Landing is the last part of a flight, where a flying animal, aircraft, or spacecraft returns to the ground. When the flying object returns to water, the process is called alighting, although it is commonly called "landing", "touchdown" or " spl ...

, with one of its wings destroyed and serious damages. It was never rebuilt. Later Soviet

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

propaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded l ...

would overstate Mozhaysky's accomplishment while downplaying the failed landing. The Grand Soviet Encyclopedia called this "the first true flight of a heavier-than-air machine in history".

*1884–1885: Ganz

The Ganz Machinery Works Holding is a Hungarian holding company. Its products are related to rail transport, power generation, and water supply, among other industries.

The original Ganz Works or Ganz ( or , ''Ganz companies'', formerly ''Ganz ...

Company engineers Károly Zipernowsky, Ottó Bláthy

Ottó Titusz Bláthy (11 August 1860 – 26 September 1939) was a Hungarian electrical engineer. During his career he became the co-inventor of the modern electric transformer, the voltage regulator, the AC watt-hour meter, the turbo genera ...

and Miksa Déri had determined that open-core devices were impracticable, as they were incapable of reliably regulating voltage. In their joint patent application for the "Z.B.D." transformer

In electrical engineering, a transformer is a passive component that transfers electrical energy from one electrical circuit to another circuit, or multiple Electrical network, circuits. A varying current in any coil of the transformer produces ...

s, they described the design of two with no poles: the "closed-core" and the "shell-core" transformers. In the closed-core type, the primary and secondary windings were wound around a closed iron ring; in the shell type, the windings were passed ''through'' the iron core. In both designs, the magnetic flux linking the primary and secondary windings traveled almost entirely within the iron core, with no intentional path through air. When employed in electric distribution systems, this revolutionary design concept would finally make it technically and economically feasible to provide electric power for lighting in homes, businesses and public spaces.''Bláthy, Ottó Titusz (1860 – 1939)'', Hungarian Patent Office, January 29, 2004. Bláthy had suggested the use of closed-cores, Zipernowsky the use of shunt connections, and Déri had performed the experiments.Smil, Vaclav, ''Creating the Twentieth Century: Technical Innovations of 1867—1914 and Their Lasting Impact''

Oxford University Press, 2005, p. 71. Electrical and electronic systems the world over continue to rely on the principles of the original Z.B.D. transformers. The inventors also popularized the word "transformer" to describe a device for altering the EMF of an electric current, although the term had already been in use by 1882. *1884–1885:

John Philip Holland

John Philip Holland (; February 24, 1841August 12, 1914) was an Irish marine engineer who developed the first submarine to be formally commissioned by the US Navy, USS Holland (SS-1) and the first Royal Navy submarine, ''Holland 1''.

Early lif ...

and Edmund Zalinski, having formed the " Nautilus Submarine Boat Company", start working on a new submarine. The so-called " Zalinsky boat" was constructed in Hendrick's Reef (former Fort Lafayette), Bay Ridge in (ray) or (rayacus the 3rd) New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

borough

A borough is an administrative division in various English language, English-speaking countries. In principle, the term ''borough'' designates a self-governing walled town, although in practice, official use of the term varies widely.

History

...

of Brooklyn

Brooklyn is a Boroughs of New York City, borough of New York City located at the westernmost end of Long Island in the New York (state), State of New York. Formerly an independent city, the borough is coextensive with Kings County, one of twelv ...

. "The new, cigar-shaped submarine was 50 feet long with a maximum beam of eight feet. To save money, the hull was largely of wood, framed with iron hoops, and again, a Brayton-cycle engine provided motive power." The project was plagued by a "shoestring budget" and Zalinski mostly rejecting Holland's ideas on improvements. The submarine was ready for launching in September, 1885. "During the launching itself, a section of the ways collapsed under the weight of the boat, dashing the hull against some pilings and staving in the bottom. Although the submarine was repaired and eventually carried out several trial runs in lower New York Harbor, by the end of 1886 the Nautilus Submarine Boat Company was no more, and the salvageable remnants of the Zalinski Boat were sold to reimburse the disappointed investors." Holland would not create another submarine to 1893.

*1885: Galileo Ferraris

Galileo Ferraris (31 October 1847 – 7 February 1897) was an Italian university professor, physicist and electrical engineer, one of the pioneers of AC power system and inventor of the induction motor although he never patented his work. Many ne ...

of Livorno Piemonte, Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy (, ) was a unitary state that existed from 17 March 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 10 June 1946, when the monarchy wa ...

reaches the concept of a rotating magnetic field A rotating magnetic field (RMF) is the resultant magnetic field produced by a system of Electromagnetic coil, coils symmetrically placed and supplied with Polyphase system, polyphase currents. A rotating magnetic field can be produced by a poly-phas ...

. He applied it to a new motor. "Ferraris devised a motor using electromagnets at right angles and powered by alternating currents that were 90° out of phase, thus producing a revolving magnetic field. The motor, the direction of which could be reversed by reversing its polarity, proved the solution to the last remaining problem in alternating-current motors. The principle made possible the development of the asynchronous, self-starting electric motor

An electric motor is a machine that converts electrical energy into mechanical energy. Most electric motors operate through the interaction between the motor's magnetic field and electric current in a electromagnetic coil, wire winding to gene ...

that is still used today. Believing that the scientific and intellectual values of new developments far outstripped material values, Ferraris deliberately did not patent his invention; on the contrary, he demonstrated it freely in his own laboratory to all comers." He published his findings in 1888. By then, Nikola Tesla

Nikola Tesla (;"Tesla"

. ''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. ; 10 July 1856 – 7 ...

had independently reached the same concept and was seeking a patent.

*1885: Nikolay Bernardos and Karol Olszewski of Broniszów were granted a patent for their Electrogefest, an "electric arc welder with a carbon electrode". Introducing a method of . ''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. ; 10 July 1856 – 7 ...

carbon arc welding

Carbon arc welding (CAW) is an arc welding process which produces coalescence of metals by heating them with an arc between a non-consumable carbon (graphite) electrode and the work-piece. It was the first arc-welding process developed but is not ...

, they also became the "inventors of modern welding apparatus".

*1885–1888:

*1885–1888: Karl Benz

Carl (or Karl) Friedrich Benz (; born Karl Friedrich Michael Vaillant; 25 November 1844 – 4 April 1929) was a German engine designer and automotive engineer. His Benz Patent-Motorwagen from 1885 is considered the first practical modern automo ...

of Karlsruhe

Karlsruhe ( ; ; ; South Franconian German, South Franconian: ''Kallsruh'') is the List of cities in Baden-Württemberg by population, third-largest city of the States of Germany, German state of Baden-Württemberg, after its capital Stuttgart a ...

, Baden

Baden (; ) is a historical territory in southern Germany. In earlier times it was considered to be on both sides of the Upper Rhine, but since the Napoleonic Wars, it has been considered only East of the Rhine.

History

The margraves of Ba ...

, German Empire

The German Empire (),; ; World Book, Inc. ''The World Book dictionary, Volume 1''. World Book, Inc., 2003. p. 572. States that Deutsches Reich translates as "German Realm" and was a former official name of Germany. also referred to as Imperia ...

introduces the Benz Patent Motorwagen, widely regarded as the first automobile

A car, or an automobile, is a motor vehicle with wheels. Most definitions of cars state that they run primarily on roads, Car seat, seat one to eight people, have four wheels, and mainly transport private transport#Personal transport, peopl ...

. It featured wire wheels (unlike carriages' wooden ones) with a four-stroke engine of his own design between the rear wheels, with a very advanced coil ignition G.N. Georgano and evaporative cooling rather than a radiator. The ''Motorwagen'' was patented on January 29, 1886, as ''DRP-37435: "automobile fueled by gas"''. The 1885 version was difficult to control, leading to a collision with a wall during a public demonstration. The first successful tests on public roads were carried out in the early summer of 1886. The next year Benz created the ''Motorwagen Model 2'' which had several modifications, and in 1887, the definitive ''Model 3'' with wooden wheels was introduced, showing at the Paris Expo the same year. Benz began to sell the vehicle (advertising it as the ''Benz Patent Motorwagen'') in the late summer of 1888, making it the first commercially available automobile in history.

*1885–1887: William Stanley, Jr. of Brooklyn

Brooklyn is a Boroughs of New York City, borough of New York City located at the westernmost end of Long Island in the New York (state), State of New York. Formerly an independent city, the borough is coextensive with Kings County, one of twelv ...

, New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

New York may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* ...

, an employee of George Westinghouse

George Westinghouse Jr. (October 6, 1846 – March 12, 1914) was a prolific American inventor, engineer, and entrepreneurial industrialist based in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. He is best known for his creation of the railway air brake and for bei ...

, creates an improved transformer

In electrical engineering, a transformer is a passive component that transfers electrical energy from one electrical circuit to another circuit, or multiple Electrical network, circuits. A varying current in any coil of the transformer produces ...

. Westinghouse had bought the patents of Lucien Gaulard

Lucien Gaulard (16 July 1850 – 26 November 1888) was a French engineer who invented devices for the transmission of alternating current electrical energy.

Biography

Gaulard was born in Paris, France in 1850.

A power transformer developed by G ...

and John Dixon Gibbs

John Dixon Gibbs (1834–1912) was a British engineer and financier who, together with Lucien Gaulard, is often credited as the co-inventor of the AC step-down transformer. The transformer was first demonstrated in 1883 at London's Royal Aquari ...

on the subject, and had purchased an option on the designs of Károly Zipernowsky, Ottó Bláthy

Ottó Titusz Bláthy (11 August 1860 – 26 September 1939) was a Hungarian electrical engineer. During his career he became the co-inventor of the modern electric transformer, the voltage regulator, the AC watt-hour meter, the turbo genera ...

and Miksa Déri. He entrusted engineer Stanley with the building of a device for commercial use. Stanley's first patented design was for induction coil

An induction coil or "spark coil" ( archaically known as an inductorium or Ruhmkorff coil after Heinrich Rühmkorff) is a type of transformer used to produce high-voltage pulses from a low-voltage direct current (DC) supply. p.98 To create the ...

s with single cores of soft iron and adjustable gaps to regulate the EMF present in the secondary winding. This design was first used commercially in 1886. But Westinghouse soon had his team working on a design whose core comprised a stack of thin "E-shaped" iron plates, separated individually or in pairs by thin sheets of paper or other insulating material. Prewound copper coils could then be slid into place, and straight iron plates laid in to create a closed magnetic circuit. Westinghouse applied for a patent for the new design in December 1886; it was granted in July 1887.

*1885–1889: Claude Goubet, a French inventor, builds two small electric submarines. The first Goubet model was 16-feet long and weighed 2 tons. "She used accumulators (storage batteries

A rechargeable battery, storage battery, or secondary cell (formally a type of Accumulator (energy), energy accumulator), is a type of electrical battery which can be charged, discharged into a load, and recharged many times, as opposed to a ...

which operated an Edison-type dynamo." While among the earliest submarines to successfully make use of electric power, she proved to have a severe flaw. She could not stay at a stable depth, set by the operator. The improved Goubet II was introduced in 1889. This version could transport a 2-man crew and had "an attractive interior". More stable than her predecessor, though still unable to stay at a set depth.

*1885–1887: Thorsten Nordenfelt of Örby, Uppsala Municipality

Uppsala Municipality () is a municipality in Uppsala County in east central Sweden. Uppsala has a population of 211,411 (2016-06-30). Its seat is located in the university city of Uppsala.

Uppsala Municipality was created through amalgamations t ...

, Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. It borders Norway to the west and north, and Finland to the east. At , Sweden is the largest Nordic count ...

produces a series of steam powered submarines

A submarine (often shortened to sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. (It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability.) The term "submarine" is also sometimes used historically or info ...

. The first was the ''Nordenfelt I'', a 56 tonne, 19.5 metre long vessel similar to George Garrett's ill-fated ''Resurgam

''Resurgam'' (Latin: "I shall rise again") is an early submarine from the Victorian era and its prototype, designed and built in Britain by Reverend George Garrett. She was intended as a weapon to penetrate the chain netting placed around shi ...

'' (1879), with a range of 240 kilometres and armed with a single torpedo and a 25.4 mm machine gun. It was manufactured by Bolinders in Stockholm

Stockholm (; ) is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in Sweden by population, most populous city of Sweden, as well as the List of urban areas in the Nordic countries, largest urban area in the Nordic countries. Approximately ...

in 1884–1885. Like the Resurgam, it operated on the surface using a 100 HP steam engine with a maximum speed of 9 kn, then it shut down its engine to dive. She was purchased by the Hellenic Navy

The Hellenic Navy (HN; , abbreviated ΠΝ) is the Navy, naval force of Greece, part of the Hellenic Armed Forces. The modern Greek navy historically hails from the naval forces of various Aegean Islands, which fought in the Greek War of Independ ...

and was delivered to Salamis Naval Base in 1886. Following the acceptance tests, she was never used again by the Hellenic Navy and was scrapped in 1901. Nordenfelt then built the ''Nordenfelt II'' (''Abdülhamid'') in 1886 and ''Nordenfelt III'' (''Abdülmecid'') in 1887, a pair of 30 metre long submarines with twin torpedo tubes, for the Ottoman Navy

The Ottoman Navy () or the Imperial Navy (), also known as the Ottoman Fleet, was the naval warfare arm of the Ottoman Empire. It was established after the Ottomans first reached the sea in 1323 by capturing Praenetos (later called Karamürsel ...

. ''Abdülhamid'' became the first submarine in history to fire a torpedo while submerged under water. The Nordenfelts had several faults. "It took as long as twelve hours to generate enough steam for submerged operations and about thirty minutes to dive. Once underwater, sudden changes in speed or direction triggered—in the words of a U.S. Navy intelligence report—"dangerous and eccentric movements." ...However, good public relations overcame bad design: Nordenfeldt always demonstrated his boats before a stellar crowd of crowned heads, and Nordenfeldt's submarines were regarded as the world standard."

*1886–1887: Carl Gassner of Mainz

Mainz (; #Names and etymology, see below) is the capital and largest city of the German state of Rhineland-Palatinate, and with around 223,000 inhabitants, it is List of cities in Germany by population, Germany's 35th-largest city. It lies in ...

, German Empire

The German Empire (),; ; World Book, Inc. ''The World Book dictionary, Volume 1''. World Book, Inc., 2003. p. 572. States that Deutsches Reich translates as "German Realm" and was a former official name of Germany. also referred to as Imperia ...

receives a patent for a zinc–carbon battery, among the earliest examples of dry cell

An electric battery is a source of electric power consisting of one or more electrochemical cells with external connections for powering electrical devices. When a battery is supplying power, its positive terminal is the cathode and its nega ...

batteries. Originally patented in the German Empire, Gassner also received patents from Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military ...

, Belgium

Belgium, officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. Situated in a coastal lowland region known as the Low Countries, it is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeas ...

, the French Third Republic

The French Third Republic (, sometimes written as ) was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 1940, after the Fall of France durin ...

, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was the union of the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland into one sovereign state, established by the Acts of Union 1800, Acts of Union in 1801. It continued in this form until ...

(all in 1886) and the United States (in 1887). Consumer dry cells would first appear in the 1890s. In 1887, Wilhelm Hellesen of Kalundborg

Kalundborg () is a Danish city with a population of 16,659 (1 January 2025),Denmark

Denmark is a Nordic countries, Nordic country in Northern Europe. It is the metropole and most populous constituent of the Kingdom of Denmark,, . also known as the Danish Realm, a constitutionally unitary state that includes the Autonomous a ...

patented his own zinc–carbon battery. Within the year, Hellesen and V. Ludvigsen founded a factory in Frederiksberg

Frederiksberg () is a part of the Capital Region of Denmark. It is an independent municipality, Frederiksberg Municipality, separate from Copenhagen Municipality, but both are a part of the region of Copenhagen. It occupies an area of less tha ...

, producing their batteries.

*1886: Charles Martin Hall

Charles Martin Hall (December 6, 1863 – December 27, 1914) was an American inventor, businessman, and chemist. He is best known for his invention in 1886 of an inexpensive method for producing aluminium, which became the first metal to att ...

of Thompson Township, Geauga County, Ohio

Thompson Township is one of the sixteen townships of Geauga County, Ohio, United States. As of the 2020 census the population was 2,144.

Geography

Located in the northeastern corner of the county, it borders the following townships:

* Madison ...

, and Paul Héroult

Paul (Louis-Toussaint) Héroult (10 April 1863 – 9 May 1914) was a French scientist. He was one of the inventors of the Hall-Héroult process for smelting aluminium, and developed the first successful commercial electric arc furnace. He li ...

of Thury-Harcourt

Thury-Harcourt () is a former Communes of France, commune in the Calvados (department), Calvados Departments of France, department in the Normandy (administrative region), Normandy Regions of France, region in northwestern France. On 1 January 201 ...

, Normandy

Normandy (; or ) is a geographical and cultural region in northwestern Europe, roughly coextensive with the historical Duchy of Normandy.

Normandy comprises Normandy (administrative region), mainland Normandy (a part of France) and insular N ...

independently discover the same inexpensive method for producing aluminium

Aluminium (or aluminum in North American English) is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol Al and atomic number 13. It has a density lower than that of other common metals, about one-third that of steel. Aluminium has ...

, which became the first metal to attain widespread use since the prehistoric discovery of iron

Iron is a chemical element; it has symbol Fe () and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, forming much of Earth's o ...

. The basic invention involves passing an electric current through a bath of alumina

Aluminium oxide (or aluminium(III) oxide) is a chemical compound of aluminium and oxygen with the chemical formula . It is the most commonly occurring of several aluminium oxides, and specifically identified as aluminium oxide. It is commonly ...

dissolved in cryolite

Cryolite ( Na3 Al F6, sodium hexafluoroaluminate) is a rare mineral identified with the once-large deposit at Ivittuut on the west coast of Greenland, mined commercially until 1987.

It is used in the reduction ("smelting") of aluminium, in pest ...

, which results in a puddle of aluminum forming in the bottom of the retort. It has come to be known as the Hall-Héroult process. Often overlooked is that Hall did not work alone. His research partner was Julia Brainerd Hall, an older sister. She had studied chemistry at Oberlin College

Oberlin College is a Private university, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college and conservatory of music in Oberlin, Ohio, United States. Founded in 1833, it is the oldest Mixed-sex education, coeducational lib ...

, helped with the experiments, took laboratory notes and gave business advice to Charles.

*1886–1890: Herbert Akroyd Stuart of Halifax Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ) is an area of Northern England which was History of Yorkshire, historically a county. Despite no longer being used for administration, Yorkshire retains a strong regional identity. The county was named after its county town, the ...

, England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

receives his first patent on a prototype of the hot bulb engine

The hot-bulb engine, also known as a semi-diesel or Akroyd engine, is a type of internal combustion engine in which fuel Combustion, ignites by coming in contact with a red-hot metal surface inside a bulb, followed by the introduction of air (ox ...

. His research culminated in an 1890 patent for a compression ignition engine. Production started in 1891 by Richard Hornsby & Sons

Richard Hornsby & Sons was an engine and machinery manufacturer in Grantham, Lincolnshire, Grantham, Lincolnshire, England from 1828 until 1918. The company was a pioneer in the manufacture of the Hornsby-Akroyd oil engine, oil engine develop ...

of Grantham

Grantham () is a market town and civil parish in the South Kesteven district of Lincolnshire, England, situated on the banks of the River Witham and bounded to the west by the A1 road (Great Britain), A1 road. It lies south of Lincoln, England ...

, Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire (), abbreviated ''Lincs'', is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the East Midlands and Yorkshire and the Humber regions of England. It is bordered by the East Riding of Yorkshire across the Humber estuary to th ...

, England under the title Hornsby Akroyd Patent Oil Engine under licence.Herbert Akroyd Stuart, ''Improvements in Engines Operated by the Explosion of Mixtures of Combustible Vapour or Gas and Air'', British Patent No 7146, Mai 1890 Stuart's oil engine design was simple, reliable and economical. It had a comparatively low compression ratio, so that the temperature of the air compressed in the combustion chamber at the end of the compression stroke was not high enough to initiate combustion. Combustion instead took place in a separated combustion chamber, the "vaporizer" (also called the "hot bulb") mounted on the cylinder head, into which fuel was sprayed. It was connected to the cylinder by a narrow passage and was heated either by the cylinder's coolant or by exhaust gases while running; an external flame such as a blowtorch was used for starting. Self-ignition occurred from contact between the fuel-air mixture and the hot walls of the vaporizer.

*1887: William Thomson (later Baron Kelvin) of Belfast

Belfast (, , , ; from ) is the capital city and principal port of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan and connected to the open sea through Belfast Lough and the North Channel (Great Britain and Ireland), North Channel ...

, Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

introduces the multicellular voltmeter

A voltmeter is an instrument used for measuring electric potential difference between two points in an electric circuit. It is connected in parallel. It usually has a high resistance so that it takes negligible current from the circuit.

A ...

. The electrical supply industry needed instruments capable of measuring high voltages. Thomson's voltmeter could measure up to 20,000 volts. It could measure both direct current

Direct current (DC) is one-directional electric current, flow of electric charge. An electrochemical cell is a prime example of DC power. Direct current may flow through a conductor (material), conductor such as a wire, but can also flow throug ...

(DC) and alternating current

Alternating current (AC) is an electric current that periodically reverses direction and changes its magnitude continuously with time, in contrast to direct current (DC), which flows only in one direction. Alternating current is the form in w ...

(AC) flows. They went into production in 1888, being the first electrostatic voltmeter

Electrostatic voltmeter can refer to an electrostatic charge meter, known also as surface DC voltmeter, or to a voltmeter to measure large electrical potentials, traditionally called electrostatic voltmeter.

Charge meter

A surface DC voltmeter is ...

s.

*1887: Charles Vernon Boys of Wing, Rutland

Wing is a village and civil parishes in England, civil parish in the East Midlands county of Rutland, England. The population was 315 at the 2001 census and 314 at that of 2011. It features a fine church and a labyrinth made of turf. Rutland Wat ...

, England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

introduces a method of using fused quartz

Fused quartz, fused silica or quartz glass is a glass consisting of almost pure silica (silicon dioxide, SiO2) in amorphous (non-crystalline) form. This differs from all other commercial glasses, such as soda-lime glass, lead glass, or borosi ...

fibers to measure "delicate forces". Boys was a physics demonstrator at the Royal College of Science in South Kensington

South Kensington is a district at the West End of Central London in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Historically it settled on part of the scattered Middlesex village of Brompton. Its name was supplanted with the advent of the ra ...

, but was contacting private experiments on the effects of delicate forces on objects. It was already known that hanging an object from a thread could demonstrate the effects of such weak influences. Said thread had to be "thin, strong and elastic". Finding the best fibers available at the time insufficient for his experiments, Boys set out to create a better fiber. He tried making glass from a variety of minerals. The best results came from natural quartz

Quartz is a hard, crystalline mineral composed of silica (silicon dioxide). The Atom, atoms are linked in a continuous framework of SiO4 silicon–oxygen Tetrahedral molecular geometry, tetrahedra, with each oxygen being shared between two tet ...

. He created fibers both extremely thin and highly durable. He used them to create the "radiomicrometer", a device sensitive enough to detect the heat of a single candle from a distance of almost 2 miles. By March 26, 1887, Boys was reporting his results to the Physical Society of London

The Physical Society of London, England, was a scientific society which was founded in 1874. In 1921, it was renamed the Physical Society, and in 1960 it merged with the Institute of Physics (IOP), the combined organisation eventually adopting the ...

.

*1887–1888: Augustus Desiré Waller of Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

recorded the human electrocardiogram with surface electrodes

An electrode is an electrical conductor used to make contact with a nonmetallic part of a circuit (e.g. a semiconductor, an electrolyte, a vacuum or a gas). In electrochemical cells, electrodes are essential parts that can consist of a variety ...

. He was employed at the time as a lecturer in physiology at St Mary's Hospital in Paddington