|

Special Pleading

Special pleading is an informal fallacy wherein a person claims an exception to a general or universal principle, but the exception is unjustified. It applies a double standard. In the classic distinction among material fallacies, cognitive fallacies, and formal fallacies, special pleading most likely falls within the category of cognitive fallacy, because it would seem to relate to " lip service", rationalization, and diversion (abandonment of discussion). Special pleading also often resembles the "appeal to" logical fallacies. In medieval philosophy, it was not presumed that wherever a distinction is claimed, a relevant basis for the distinction should exist and be substantiated. Special pleading subverts a presumption of existential import. Examples A difficult case is when a possible criticism is made relatively immune to investigation. This immunity may take the forms of: * Creation of an '' ad-hoc'' exception to prevent the rule from backfiring against the claim: ** ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] [Amazon] |

Fallacy

A fallacy is the use of invalid or otherwise faulty reasoning in the construction of an argument that may appear to be well-reasoned if unnoticed. The term was introduced in the Western intellectual tradition by the Aristotelian '' De Sophisticis Elenchis''. Fallacies may be committed intentionally to manipulate or persuade by deception, unintentionally because of human limitations such as carelessness, cognitive or social biases and ignorance, or potentially due to the limitations of language and understanding of language. These delineations include not only the ignorance of the right reasoning standard but also the ignorance of relevant properties of the context. For instance, the soundness of legal arguments depends on the context in which they are made. Fallacies are commonly divided into "formal" and "informal". A formal fallacy is a flaw in the structure of a deductive argument that renders the argument invalid, while an informal fallacy originates in an error in ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] [Amazon] |

Ad Hoc Hypothesis

In science and philosophy, an ''ad hoc'' hypothesis is a hypothesis added to a theory in order to save it from being falsified. For example, a person that wants to believe in leprechauns can avoid ever being proven wrong by using ''ad hoc'' hypotheses (e.g., by adding "they are invisible", then "their motives are complex", and so on).Stanovich, Keith E. (2007). How to Think Straight About Psychology. Boston: Pearson Education. Pages 19-33 Often, ''ad hoc'' hypothesizing is employed to compensate for anomalies not anticipated by the theory in its unmodified form. In the scientific community Scientists are often skeptical of theories that rely on frequent, unsupported adjustments to sustain them. This is because, if a theorist so chooses, there is no limit to the number of ''ad hoc'' hypotheses that they could add. Thus the theory becomes more and more complex, but is never falsified. This is often at a cost to the theory's predictive power, however. ''Ad hoc'' hypotheses are ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] [Amazon] |

No True Scotsman

No true Scotsman or appeal to purity is an informal fallacy in which one modifies a prior claim in response to a counterexample by asserting the counterexample is excluded by definition. Rather than admitting error or providing evidence to disprove the counterexample, the original claim is changed by using a non-substantive modifier such as "true", "pure", "genuine", "authentic", "real", or other similar terms. Philosopher Bradley Dowden explains the fallacy as an " ad hoc rescue" of a refuted generalization attempt. The following is a simplified rendition of the fallacy: Person A: "No Scotsman puts sugar on his porridge." Person B: "But my uncle Angus is a Scotsman and he puts sugar on his porridge." Person A: "But no Scotsman puts sugar on his porridge." Occurrence The "no true Scotsman" fallacy is committed when the arguer satisfies the following conditions: * not publicly retreating from the initial, falsified ''a posteriori'' assertion * offering a modified assertion t ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] [Amazon] |

Moving The Goalposts

Moving the goalposts (or shifting the goalposts) is a metaphor, derived from goal-based sports such as football and hockey, that means to change the rule or criterion ("goal") of a process or competition while it is still in progress, in such a way that the new goal offers one side an advantage or disadvantage. Etymology This phrase is British in origin and derives from sports that use goalposts. The figurative use alludes to the perceived unfairness in changing the goal one is trying to achieve after the process one is engaged in (such as a game of football) has already started. Logical fallacy Moving the goalposts is an informal fallacy in which evidence presented in response to a specific claim is dismissed and some other (often greater) evidence is demanded. That is, after an attempt has been made to score a goal, the goalposts are moved to exclude the attempt. The problem with changing the rules of the game is that the meaning of the result is changed, too. Use Some inclu ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] [Amazon] |

Hard Cases Make Bad Law

Hard cases make bad law is an adage or legal maxim meaning that an extreme case is a poor basis for a general law that would cover a wider range of less extreme cases. In other words, a general law is better drafted for the average circumstance as this will be more common. The original meaning of the phrase concerned cases in which the law had a hard impact on some person whose situation aroused sympathy. The expression dates at least to 1837. It was used in 1904 by US Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. Its validity has since been questioned and dissenting variations include the phrase "Bad law makes hard cases", and even its opposite, "Hard cases make good law". Discussion The maxim dates at least to 1837, when a judge, ruling in favor of a parent against the maintenance of her children, said, "We have heard that hard cases make bad law." The judge's wording suggests that the phrase was not new then. Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. made a utilitarian argument for this in ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] [Amazon] |

Exception That Proves The Rule

"The exception that proves the rule" is a saying whose meaning is contested. Henry Watson Fowler's ''Modern English Usage'' identifies five ways in which the phrase has been used, and each use makes some sort of reference to the role that a particular case or event takes in relation to a more general rule. Two original meanings of the phrase are usually cited. The first, preferred by Fowler, is that the presence of an exception applying to a ''specific'' case establishes ("proves") that a ''general'' rule exists. A more explicit phrasing might be "the exception that proves ''the existence of'' the rule." Most contemporary uses of the phrase emerge from this origin, although often in a way which is closer to the idea that all rules have their exceptions. The alternative origin given is that the word "prove" is used in the archaic sense of "test", a reading advocated, for example, by a 1918 ''Detroit News'' style guide:''The exception proves the rule'' is a phrase that arises from ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] [Amazon] |

Courtier's Reply

The courtier's reply is an alleged type of informal fallacy, coined by American biologist PZ Myers, in which a respondent to criticism claims that the critic lacks sufficient knowledge, credentials, or training to pose any sort of criticism whatsoever.Myers, PZ (December 24, 2006)"The Courtier's Reply" Pharyngula. It may be considered an inverted form of argument from authority, where a person without authority disagreeing with authority is presumed incorrect ''prima facie''. A key element of a courtier's reply, which distinguishes it from an otherwise valid response that incidentally points out the critic's lack of established authority on the topic, is that the respondent never shows how the work of these overlooked experts invalidates the arguments that were advanced by the critic. Critics of the idea that the courtier's reply is a real fallacy have called it the "Myers shuffle", implying calling someone out for an alleged courtier's reply is a kind of rhetorical dodge or trick. ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] [Amazon] |

Cherry Picking (fallacy)

Cherry picking, suppressing evidence, or the fallacy of incomplete evidence is the act of pointing to individual cases or data that seem to confirm a particular position while ignoring a significant portion of related and similar cases or data that may contradict that position. Cherry picking may be committed intentionally or unintentionally. The term is based on the perceived process of harvesting fruit, such as cherries. The picker would be expected to select only the ripest and healthiest fruits. An observer who sees only the selected fruit may thus wrongly conclude that most, or even all, of the tree's fruit is in a likewise good condition. This can also give a false impression of the quality of the fruit (since it is only a sample and is not a representative sample). A concept sometimes confused with cherry picking is the idea of gathering only the fruit that is easy to harvest, while ignoring other fruit that is higher up on the tree and thus more difficult to obtain (see ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] [Amazon] |

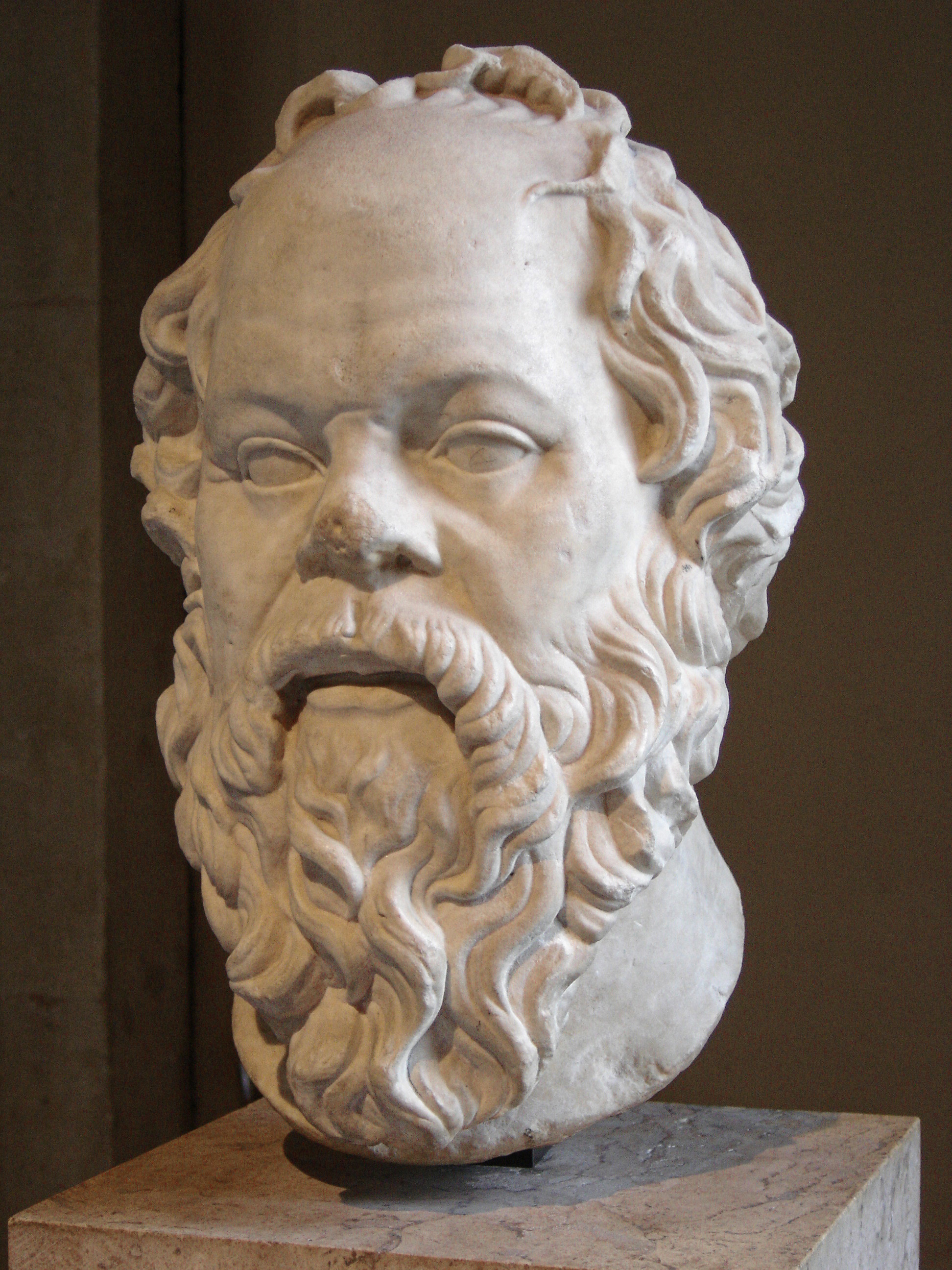

Existential Import

A syllogism (, ''syllogismos'', 'conclusion, inference') is a kind of logical argument that applies deductive reasoning to arrive at a conclusion based on two propositions that are asserted or assumed to be true. In its earliest form (defined by Aristotle in his 350 BC book '' Prior Analytics''), a deductive syllogism arises when two true premises (propositions or statements) validly imply a conclusion, or the main point that the argument aims to get across. For example, knowing that all men are mortal (major premise), and that Socrates is a man (minor premise), we may validly conclude that Socrates is mortal. Syllogistic arguments are usually represented in a three-line form: All men are mortal. Socrates is a man. Therefore, Socrates is mortal.In antiquity, two rival syllogistic theories existed: Aristotelian syllogism and Stoic syllogism. From the Middle Ages onwards, ''categorical syllogism'' and ''syllogism'' were usually used interchangeably. This article is concerne ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] [Amazon] |

Double Standard

A double standard is the application of different sets of principles for situations that are, in principle, the same. It is often used to describe treatment whereby one group is given more latitude than another. A double standard arises when two or more people, groups, organizations, circumstances, or events are treated differently even though they should be treated the same way. A double standard "implies that two things which are the same are measured by different standards". Applying different principles to similar situations may or may not indicate a double standard. To distinguish between the application of a double standard and a valid application of different standards toward circumstances that only ''appear'' to be the same, several factors must be examined. One is the sameness of those circumstances – what are the parallels between those circumstances, and in what ways do they differ? Another is the philosophy or belief system informing which principles should be appli ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] [Amazon] |

Association Fallacy

The association fallacy is a formal fallacy that asserts that properties of one thing must also be properties of another thing if both things belong to the same group. For example, a fallacious arguer may claim that "bears are animals, and bears are dangerous; therefore your dog, which is also an animal, must be dangerous." When it is an attempt to win favor by exploiting the audience's preexisting spite or disdain for something else, it is called guilt by association or an appeal to spite (). Guilt by association can be a component of ad hominem arguments which attack the speaker rather than addressing the claims, but they are a distinct class of fallacious argument, and both are able to exist independently of the other. Formal version Using the language of set theory, the formal fallacy can be written as follows: :Premise: A is in set S1 :Premise: A is in set S2 :Premise: B is also in set S2 :Conclusion: Therefore, B is in set S1. In the notation of first-order logic, this t ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] [Amazon] |

List Of Fallacies

A fallacy is the use of invalid or otherwise faulty reasoning in the construction of an argument. All forms of human communication can contain fallacies. Because of their variety, fallacies are challenging to classify. They can be classified by their structure (formal fallacies) or content (informal fallacies). Informal fallacies, the larger group, may then be subdivided into categories such as improper presumption, faulty generalization, error in assigning causation, and relevance, among others. The use of fallacies is common when the speaker's goal of achieving common agreement is more important to them than utilizing sound reasoning. When fallacies are used, the premise should be recognized as not well-grounded, the conclusion as unproven (but not necessarily false), and the argument as unsound. Formal fallacies A formal fallacy is an error in the argument's form. All formal fallacies are types of . * Appeal to probability – taking something for granted because it wo ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] [Amazon] |