|

Fertility Factor (bacteria)

The F-plasmid (first named F by one of its discoverers Esther Lederberg;also called the sex factor in ''E. coli'',the F sex factor, the fertility factor, or simply the F factor) allows genes to be transferred from one bacterium carrying the factor to another bacterium lacking the factor by conjugation. The F factor was the first plasmid to be discovered. Unlike other plasmids, F factor is constitutive for transfer proteins due to a mutation in the gene ''finO''. The F plasmid belongs to F-like plasmids, a class of conjugative plasmids that control sexual functions of bacteria with a fertility inhibition (Fin) system. Discovery Esther M. Lederberg and Luigi L. Cavalli-Sforza discovered "F," subsequently publishing with Joshua Lederberg. Once her results were announced, two other labs joined the studies. "This was not a simultaneous independent discovery of F (I named this as Fertility Factor until it was understood.) We wrote to Hayes, Jacob, & Wollman who then proceeded ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Esther Lederberg

Esther Miriam Zimmer Lederberg (December 18, 1922 – November 11, 2006) was an American microbiologist and a pioneer of bacterial genetics. She discovered the bacterial virus lambda phage and the bacterial fertility factor F, devised the first implementation of replica plating, and furthered the understanding of the transfer of genes between bacteria by specialized transduction. Lederberg also founded and directed the now-defunct Plasmid Reference Center at Stanford University, where she maintained, named, and distributed plasmids of many types, including those coding for antibiotic resistance, heavy metal resistance, virulence, conjugation, colicins, transposons, and other unknown factors. As a woman in a male-dominated field and the wife of Nobel laureate Joshua Lederberg, Esther Lederberg struggled for professional recognition. Despite her foundational discoveries in the field of microbiology, she was never offered a tenured position at a university. Textbooks often ig ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

TraJ 5' UTR

The traJ 5' UTR is a cis acting RNA element which is involved in regulating plasmid transfer in bacteria. In conjugating bacteria the FinOP system regulates the transfer of F-like plasmids. The FinP gene encodes an antisense RNA product that is complementary to part of the 5' UTR of the traJ mRNA. The traJ gene encodes a protein required for transcription from the major transfer promoter, pY. The FinO protein is essential for effective repression, acting by binding to FinP and protecting it from RNase Ribonuclease (commonly abbreviated RNase) is a type of nuclease that catalyzes the degradation of RNA into smaller components. Ribonucleases can be divided into endoribonucleases and exoribonucleases, and comprise several sub-classes within the ... E degradation. References External links * * Cis-regulatory RNA elements {{molecular-cell-biology-stub ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Bacteriology

Bacteriology is the branch and specialty of biology that studies the Morphology (biology), morphology, ecology, genetics and biochemistry of bacteria as well as many other aspects related to them. This subdivision of microbiology involves the identification, classification, and characterization of bacterial species. Because of the similarity of thinking and working with microorganisms other than bacteria, such as protozoa, fungi, and non-microorganism viruses, there has been a tendency for the field of bacteriology to extend as microbiology. The terms were formerly often used interchangeably. However, bacteriology can be classified as a distinct science. Overview Definition Bacteriology is the study of bacteria and their relation to medicine. Bacteriology evolved from physicians needing to apply the Germ theory of disease, germ theory to address the concerns relating to disease spreading in hospitals the 19th century. Identification and characterizing of bacteria being associ ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Fosmid

Fosmids are similar to cosmids but are based on the bacterial F-plasmid. The cloning vector is limited, as a host (usually ''E. coli'') can only contain one fosmid molecule. Fosmids can hold DNA inserts of up to 40 kb in size; often the source of the insert is random genomic DNA. A fosmid library is prepared by extracting the genomic DNA from the target organism and cloning it into the fosmid vector. The ligation mix is then packaged into phage particles and the DNA is transfected into the bacterial host. Bacterial clones propagate the fosmid library. The low copy number offers higher stability than vectors with relatively higher copy numbers, including cosmids. Fosmids may be useful for constructing stable libraries from complex genomes. Fosmids have high structural stability and have been found to maintain human DNA effectively even after 100 generations of bacterial growth. Fosmid clones were used to help assess the accuracy of the Public Human Genome Sequence. Discovery The fe ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

FlmB RNA

The FlmA-FlmB toxin-antitoxin system consists of FlmB RNA (F leading-region maintenance B), a family of non-coding RNAs and the protein toxin FlmA. The FlmB RNA transcript is 100 nucleotides in length and is homologous to sok RNA from the hok/sok system and fulfills the identical function as a post-segregational killing (PSK) mechanism. flmB is found on the F-plasmid of ''Escherichia coli'' and ''Salmonella enterica''. It is responsible for stabilising the plasmid. If the plasmid is not inherited, long-lived FlmA mRNA and protein will be highly toxic to the cell, possibly to the point of causing cell death. Daughter cells which inherit the plasmid inherit the ''FlmB'' gene, coding for FlmB RNA which binds the leader sequence of FlmA mRNA and represses its translation. See also *Toxin-antitoxin system A toxin-antitoxin system consists of a "toxin" and a corresponding "antitoxin", usually encoded by closely linked genes. The toxin is usually a protein while the antitoxin can b ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

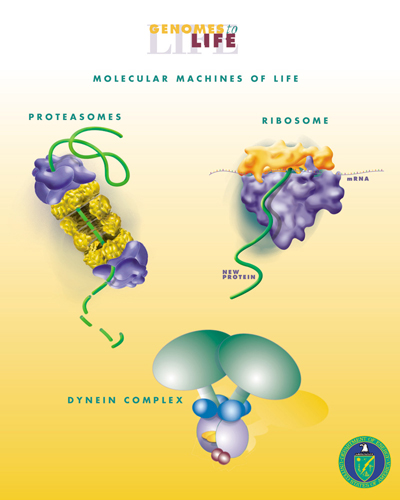

Helicase

Helicases are a class of enzymes that are vital to all organisms. Their main function is to unpack an organism's genetic material. Helicases are motor proteins that move directionally along a nucleic double helix, separating the two hybridized nucleic acid strands (hence '' helic- + -ase''), via the energy gained from ATP hydrolysis. There are many helicases, representing the great variety of processes in which strand separation must be catalyzed. Approximately 1% of eukaryotic genes code for helicases. The human genome codes for 95 non-redundant helicases: 64 RNA helicases and 31 DNA helicases. Many cellular processes, such as DNA replication, transcription, translation, recombination, DNA repair and ribosome biogenesis involve the separation of nucleic acid strands that necessitates the use of helicases. Some specialized helicases are also involved in sensing viral nucleic acids during infection and fulfill an immunological function. Genetic mutations that affect helicase ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Bacterial Artificial Chromosome

A bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) is a DNA construct, based on a functional fertility plasmid (or F-plasmid), used for transforming and cloning in bacteria, usually '' E. coli''. F-plasmids play a crucial role because they contain partition genes that promote the even distribution of plasmids after bacterial cell division. The bacterial artificial chromosome's usual insert size is 150–350 kbp. A similar cloning vector called a PAC has also been produced from the DNA of P1 bacteriophage. BACs were often used to sequence the genomes of organisms in genome projects, for example the Human Genome Project, though they have been replaced by more modern technologies. In BAC sequencing, short piece of the organism's DNA is amplified as an insert in BACs, and then sequenced. Finally, the sequenced parts are rearranged '' in silico'', resulting in the genomic sequence of the organism. BACs were replaced with faster and less laborious sequencing methods like whole genome shot ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Bioengineering

Biological engineering or bioengineering is the application of principles of biology and the tools of engineering to create usable, tangible, economically viable products. Biological engineering employs knowledge and expertise from a number of pure and applied sciences, such as mass transfer, mass and heat transfer, Kinetics (physics), kinetics, biocatalysts, biomechanics, bioinformatics, separation process, separation and List of purification methods in chemistry, purification processes, bioreactor design, surface science, fluid mechanics, thermodynamics, and polymer science. It is used in the design of medical devices, diagnostic equipment, biocompatible materials, renewable energy, ecological engineering, agricultural engineering, process engineering and catalysis, and other areas that improve the living standards of societies. Examples of bioengineering research include bacteria engineered to produce chemicals, new medical imaging technology, portable and rapid diagnosti ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

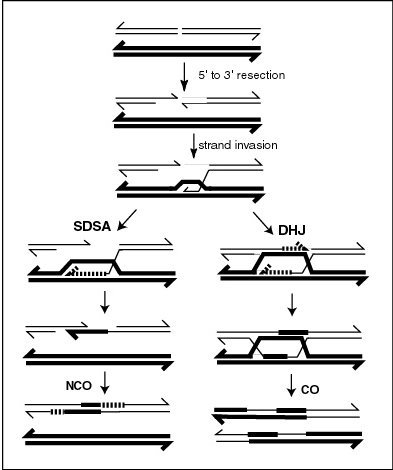

Genetic Recombination

Genetic recombination (also known as genetic reshuffling) is the exchange of genetic material between different organisms which leads to production of offspring with combinations of traits that differ from those found in either parent. In eukaryotes, genetic recombination during meiosis can lead to a novel set of genetic information that can be further passed on from parents to offspring. Most recombination occurs naturally and can be classified into two types: (1) ''interchromosomal'' recombination, occurring through independent assortment of alleles whose loci are on different but homologous chromosomes (random orientation of pairs of homologous chromosomes in meiosis I); & (2) ''intrachromosomal'' recombination, occurring through crossing over. During meiosis in eukaryotes, genetic recombination involves the pairing of homologous chromosomes. This may be followed by information transfer between the chromosomes. The information transfer may occur without physical exchange (a ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Operon

In genetics, an operon is a functioning unit of DNA containing a cluster of genes under the control of a single promoter. The genes are transcribed together into an mRNA strand and either translated together in the cytoplasm, or undergo splicing to create monocistronic mRNAs that are translated separately, i.e. several strands of mRNA that each encode a single gene product. The result of this is that the genes contained in the operon are either expressed together or not at all. Several genes must be ''co-transcribed'' to define an operon. Originally, operons were thought to exist solely in prokaryotes (which includes organelles like plastids that are derived from bacteria), but their discovery in eukaryotes was shown in the early 1990s, and are considered to be rare. In general, expression of prokaryotic operons leads to the generation of polycistronic mRNAs, while eukaryotic operons lead to monocistronic mRNAs. Operons are also found in viruses such as bacteriophages. For ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

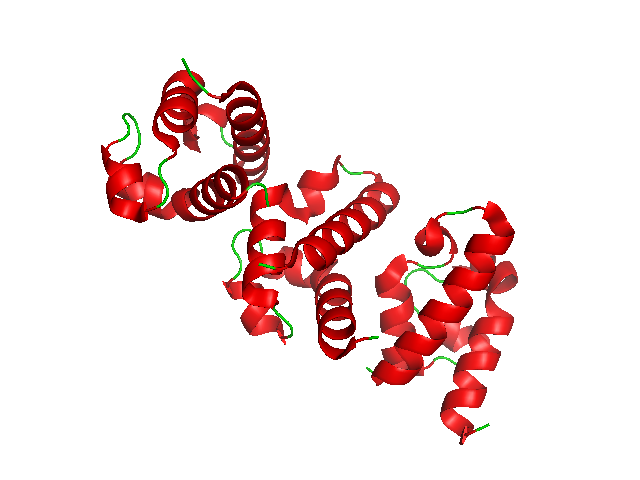

Transcription Factor

In molecular biology, a transcription factor (TF) (or sequence-specific DNA-binding factor) is a protein that controls the rate of transcription (genetics), transcription of genetics, genetic information from DNA to messenger RNA, by binding to a specific DNA sequence. The function of TFs is to regulate—turn on and off—genes in order to make sure that they are Gene expression, expressed in the desired Cell (biology), cells at the right time and in the right amount throughout the life of the cell and the organism. Groups of TFs function in a coordinated fashion to direct cell division, cell growth, and cell death throughout life; cell migration and organization (body plan) during embryonic development; and intermittently in response to signals from outside the cell, such as a hormone. There are approximately 1600 TFs in the human genome. Transcription factors are members of the proteome as well as regulome. TFs work alone or with other proteins in a complex, by promoting (a ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

FinP

FinP encodes an antisense non-coding RNA gene that is complementary to part of the TraJ 5' UTR. The FinOP system regulates the transfer of F-like plasmids. The traJ gene encodes a protein required for transcription Transcription refers to the process of converting sounds (voice, music etc.) into letters or musical notes, or producing a copy of something in another medium, including: Genetics * Transcription (biology), the copying of DNA into RNA, often th ... from the major transfer promoter, pY. The FinO protein is essential for effective repression, acting by binding to FinP and protecting it from RNase E degradation. References External links * * Antisense RNA {{molecular-cell-biology-stub ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |