|

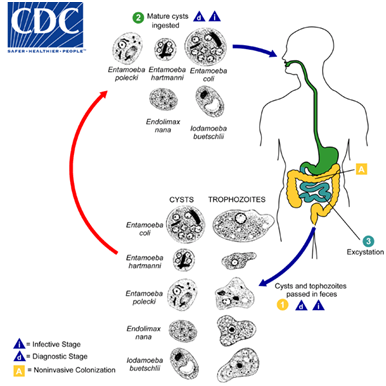

Entamoeba Coli

''Entamoeba coli'' is a non-pathogenic species of ''Entamoeba'' that frequently exists as a commensal parasite in the human gastrointestinal tract. ''E. coli'' (not to be confused with the bacterium ''Escherichia coli'') is important in medicine because it can be confused during microscopic examination of stained stool specimens with the pathogenic ''Entamoeba histolytica''. This amoeba does not move much by the use of its pseudopod, and creates a "''sur place'' (non-progressive) movement" inside the large intestine. Usually, the amoeba is immobile, and keeps its round shape. This amoeba, in its trophozoite stage, is only visible in fresh, unfixed stool specimens. Sometimes the ''Entamoeba coli'' have parasites as well. One is the fungus ''Sphaerita'' spp. This fungus lives in the cytoplasm of the ''E. coli''. While this differentiation is typically done by visual examination of the parasitic cysts via light microscopy, new methods using molecular biology techniques have been de ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Giovanni Battista Grassi

Giovanni Battista Grassi (27 March 1854 – 4 May 1925) was an Italian physician and zoologist, best known for his pioneering works on parasitology, especially on malariology. He was Professor of Comparative Zoology at the University of Catania from 1883, and Professor of Comparative Anatomy at Sapienza University of Rome from 1895 until his death. His scientific contributions covered embryological development of honey bees, on helminth parasites, the vine parasite phylloxera, on migrations and metamorphosis in eels, and on termites. He was the first to describe and establish the life cycle of the human malarial parasite, '' Plasmodium falciparum'', and discovered that only female anopheline mosquitoes are capable of transmitting the disease. His works in malaria remain a lasting controversy in the history of Nobel Prizes, because a British army surgeon Ronald Ross, who discovered the transmission of malarial parasite in birds was given the 1902 Nobel Prize in Physiology ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Diloxanide Furoate

Diloxanide is a medication used to treat amoeba infections. In places where infections are not common, it is a second line treatment after paromomycin when a person has no symptoms. For people who are symptomatic, it is used after treatment with metronidazole or tinidazole. It is taken by mouth. Diloxanide generally has mild side effects. Side effects may include flatulence, vomiting, and itchiness. During pregnancy it is recommended that it be taken after the first trimester. It is a luminal amebicide meaning that it only works on infections within the intestines. Diloxanide came into medical use in 1956. It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines. It is not commercially available in much of the developed world as of 2012. Medical uses Diloxanide furoate works only in the digestive tract and is a lumenal amebicide. It is considered second line treatment for infection with amoebas when no symptoms are present but the person is passing cysts, ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Carbarsone

Carbarsone is an organoarsenic compound used as an antiprotozoal drug for treatment of amebiasis and other infections. It was available for amebiasis in the United States as late as 1991. Thereafter, it remained available as a turkey feed additive for increasing weight gain and controlling histomoniasis (blackhead disease). Carbarsone is one of four arsenical animal drugs approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for use in poultry and/or swine, along with nitarsone, arsanilic acid, and roxarsone. In September 2013, the FDA announced that Zoetis and Fleming Laboratories Fleming may refer to: Places Australia *Fleming, Northern Territory, a town and a locality Canada * Fleming, Saskatchewan * Fleming Island (Saskatchewan) Egypt * Fleming (neighborhood), a neighborhood in Alexandria Greenland * Fleming Fjord ... would voluntarily withdraw current roxarsone, arsanilic acid, and carbarsone approvals, leaving only nitarsone approvals in place. In 2015 FDA wit ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Microarrays

A microarray is a multiplex lab-on-a-chip. Its purpose is to simultaneously detect the expression of thousands of genes from a sample (e.g. from a tissue). It is a two-dimensional array on a solid substrate—usually a glass slide or silicon thin-film cell—that assays (tests) large amounts of biological material using high-throughput screening miniaturized, multiplexed and parallel processing and detection methods. The concept and methodology of microarrays was first introduced and illustrated in antibody microarrays (also referred to as antibody matrix) by Tse Wen Chang in 1983 in a scientific publication and a series of patents. The "gene chip" industry started to grow significantly after the 1995 '' Science Magazine'' article by the Ron Davis and Pat Brown labs at Stanford University. With the establishment of companies, such as Affymetrix, Agilent, Applied Microarrays, Arrayjet, Illumina, and others, the technology of DNA microarrays has become the most sophisticated ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Polymerase Chain Reaction

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a method widely used to rapidly make millions to billions of copies (complete or partial) of a specific DNA sample, allowing scientists to take a very small sample of DNA and amplify it (or a part of it) to a large enough amount to study in detail. PCR was invented in 1983 by the American biochemist Kary Mullis at Cetus Corporation; Mullis and biochemist Michael Smith, who had developed other essential ways of manipulating DNA, were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1993. PCR is fundamental to many of the procedures used in genetic testing and research, including analysis of ancient samples of DNA and identification of infectious agents. Using PCR, copies of very small amounts of DNA sequences are exponentially amplified in a series of cycles of temperature changes. PCR is now a common and often indispensable technique used in medical laboratory research for a broad variety of applications including biomedical research ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

DNA Extraction

The first isolation of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) was done in 1869 by Friedrich Miescher. Currently, it is a routine procedure in molecular biology or forensic analyses. For the chemical method, many different kits are used for extraction, and selecting the correct one will save time on kit optimization and extraction procedures. PCR sensitivity detection is considered to show the variation between the commercial kits. What does it deliver? DNA extraction is frequently a preliminary step in many diagnostic procedures used to identify environmental viruses and bacteria and diagnose illnesses and hereditary diseases. These methods consist of, but are not limited to: Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH) technique was developed in the 1980s. The basic idea is to use a nucleic acid probe to hybridize nuclear DNA from either interphase cells or metaphase chromosomes attached to a microscopic slide. It is a molecular method used, among other things, to recognize and count parti ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Immunochromatographic

Affinity chromatography is a method of separating a biomolecule from a mixture, based on a highly specific macromolecular binding interaction between the biomolecule and another substance. The specific type of binding interaction depends on the biomolecule of interest; antigen and antibody, enzyme and substrate, receptor and ligand, or protein and nucleic acid binding interactions are frequently exploited for isolation of various biomolecules. Affinity chromatography is useful for its high selectivity and resolution of separation, compared to other chromatographic methods. Principle Affinity chromatography has the advantage of specific binding interactions between the analyte of interest (normally dissolved in the mobile phase), and a binding partner or ligand (immobilized on the stationary phase). In a typical affinity chromatography experiment, the ligand is attached to a solid, insoluble matrix—usually a polymer such as agarose or polyacrylamide—chemically modified t ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Pseudopodia

A pseudopod or pseudopodium (plural: pseudopods or pseudopodia) is a temporary arm-like projection of a eukaryotic cell membrane that is emerged in the direction of movement. Filled with cytoplasm, pseudopodia primarily consist of actin filaments and may also contain microtubules and intermediate filaments. Pseudopods are used for motility and ingestion. They are often found in amoebas. Different types of pseudopodia can be classified by their distinct appearances. Lamellipodia are broad and thin. Filopodia are slender, thread-like, and are supported largely by microfilaments. Lobopodia are bulbous and amoebic. Reticulopodia are complex structures bearing individual pseudopodia which form irregular nets. Axopodia are the phagocytosis type with long, thin pseudopods supported by complex microtubule arrays enveloped with cytoplasm; they respond rapidly to physical contact. Some pseudopodial cells are able to use multiple types of pseudopodia depending on the situation: Most of ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Trophozoites

A trophozoite (G. ''trope'', nourishment + ''zoon'', animal) is the activated, feeding stage in the life cycle of certain protozoa such as malaria-causing '' Plasmodium falciparum'' and those of the '' Giardia'' group. (The complement of the trophozoite state is the thick-walled cyst form). Life cycle stages Trophozoite and cyst stages are shown in the life cycle of ''Balantidium coli'' the causative agent of balantidiasis. In the apicomplexan life cycle the trophozoite undergoes schizogony (asexual reproduction) and develops into a schizont Apicomplexans, a group of intracellular parasites, have life cycle stages that allow them to survive the wide variety of environments they are exposed to during their complex life cycle. Each stage in the life cycle of an apicomplexan organism i ... which contains merozoites. The trophozoite life stage of '' Giardia'' colonizes and proliferates in the small intestine. Trophozoites develop during the course of the infection into cysts whi ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Entamoeba Coli Stages

''Entamoeba'' is a genus of Amoebozoa found as internal parasites or commensals of animals. In 1875, Fedor Lösch described the first proven case of amoebic dysentery in St. Petersburg, Russia. He referred to the amoeba he observed microscopically as ''Amoeba coli''; however, it is not clear whether he was using this as a descriptive term or intended it as a formal taxonomic name. The genus ''Entamoeba'' was defined by Casagrandi and Barbagallo for the species ''Entamoeba coli'', which is known to be a commensal organism. Lösch's organism was renamed ''Entamoeba histolytica'' by Fritz Schaudinn in 1903; he later died, in 1906, from a self-inflicted infection when studying this amoeba. For a time during the first half of the 20th century the entire genus ''Entamoeba'' was transferred to '' Endamoeba'', a genus of amoebas infecting invertebrates about which little is known. This move was reversed by the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature in the late 1950s, and ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Pathogenic

In biology, a pathogen ( el, πάθος, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of") in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a germ. The term ''pathogen'' came into use in the 1880s. Typically, the term ''pathogen'' is used to describe an ''infectious'' microorganism or agent, such as a virus, bacterium, protozoan, prion, viroid, or fungus. Small animals, such as helminths and insects, can also cause or transmit disease. However, these animals are usually referred to as parasites rather than pathogens. The scientific study of microscopic organisms, including microscopic pathogenic organisms, is called microbiology, while parasitology refers to the scientific study of parasites and the organisms that host them. There are several pathways through which pathogens can invade a host. The principal pathways have different episodic time frames, but soil has the longest ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |