|

Dps (DNA-binding Proteins From Starved Cells)

DNA-binding proteins from starved cells (Dps) are bacterial proteins that belong to the ferritin superfamily and are characterized by strong similarities but also distinctive differences with respect to "canonical" ferritins. Dps proteins are part of a complex bacterial defence system that protects DNA against oxidative damage and are distributed widely in the bacterial kingdom. Description Dps are highly symmetrical dodecameric proteins of 20 kDa characterized from a shell-like structure of 2:3 tetrahedral symmetry assembled from identical subunits with an external diameter of ~ 9 nm and a central cavity of ~ 4.5 nm in diameter. Dps proteins belong to the ferritin superfamily and the DNA protection is afforded by means of a double mechanism: The first was discovered in ''Escherichia coli'' Dps in 1992 and has given the name to the protein family; during stationary phase, Dps binds the chromosome non-specifically, forming a highly ordered and stable Dps-DNA co-crysta ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

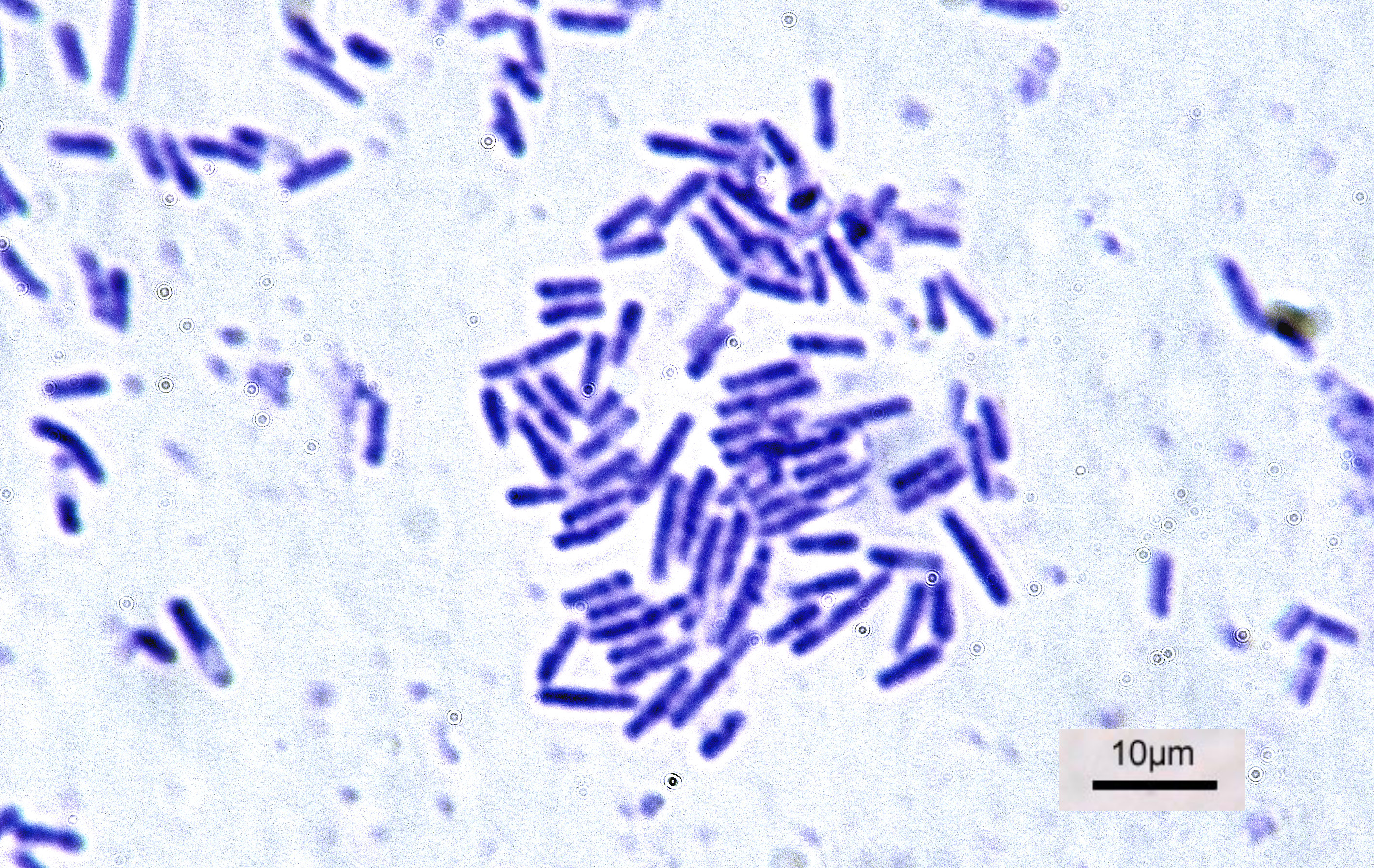

Bacterial

Bacteria (; : bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were among the first life forms to appear on Earth, and are present in most of its habitats. Bacteria inhabit the air, soil, water, acidic hot springs, radioactive waste, and the deep biosphere of Earth's crust. Bacteria play a vital role in many stages of the nutrient cycle by recycling nutrients and the fixation of nitrogen from the atmosphere. The nutrient cycle includes the decomposition of dead bodies; bacteria are responsible for the putrefaction stage in this process. In the biological communities surrounding hydrothermal vents and cold seeps, extremophile bacteria provide the nutrients needed to sustain life by converting dissolved compounds, such as hydrogen sulphide and methane, to energy. Bacteria also live in mutualistic, commensal an ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Gamma Ray

A gamma ray, also known as gamma radiation (symbol ), is a penetrating form of electromagnetic radiation arising from high energy interactions like the radioactive decay of atomic nuclei or astronomical events like solar flares. It consists of the shortest wavelength electromagnetic waves, typically shorter than those of X-rays. With frequencies above 30 exahertz () and wavelengths less than 10 picometers (), gamma ray photons have the highest photon energy of any form of electromagnetic radiation. Paul Villard, a French chemist and physicist, discovered gamma radiation in 1900 while studying radiation emitted by radium. In 1903, Ernest Rutherford named this radiation ''gamma rays'' based on their relatively strong penetration of matter; in 1900, he had already named two less penetrating types of decay radiation (discovered by Henri Becquerel) alpha rays and beta rays in ascending order of penetrating power. Gamma rays from radioactive decay are in the energy range ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Ferritin

Ferritin is a universal intracellular and extracellular protein that stores iron and releases it in a controlled fashion. The protein is produced by almost all living organisms, including archaea, bacteria, algae, higher plants, and animals. It is the primary ''intracellular iron-storage protein'' in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes, keeping iron in a soluble and non-toxic form. In humans, it acts as a buffer against iron deficiency and iron overload. Ferritin is found in most tissues as a cytosolic protein, but small amounts are secreted into the serum where it functions as an iron carrier. Plasma ferritin is also an indirect marker of the total amount of iron stored in the body; hence, serum ferritin is used as a diagnostic test for iron-deficiency anemia and iron overload. Aggregated ferritin transforms into a water insoluble, crystalline and amorphous form of storage iron called hemosiderin. Ferritin is a globular protein complex consisting of 24 protein subuni ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Transferrin

Transferrins are glycoproteins found in vertebrates which bind and consequently mediate the transport of iron (Fe) through blood plasma. They are produced in the liver and contain binding sites for two Iron(III), Fe3+ ions. Human transferrin is encoded by the ''TF'' gene and produced as a 76 Dalton (unit), kDa glycoprotein. Transferrin glycoproteins bind iron tightly, but reversibly. Although iron bound to transferrin is less than 0.1% (4 mg) of total body iron, it forms the most vital iron pool with the highest rate of turnover (25 mg/24 h). Transferrin has a molecular weight of around 80 atomic mass unit, kDa and contains two specific high-affinity Fe(III) binding sites. The affinity of transferrin for Fe(III) is extremely high (association constant is 1020 M−1 at pH 7.4) but decreases progressively with decreasing pH below neutrality. Transferrins are not limited to only binding to iron but also to different metal ions. These glycoproteins are located in various b ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Bacterioferritin

Bacterioferritin (Bfr) is an oligomeric protein containing both a binuclear iron centre and haem b. The Tertiary (chemistry), tertiary and quaternary structure of Bfr is very similar to that of ferritin. The physiological functions of BFR, which may be other than just iron uptake, are not clear. Structure The structure of Bfr has been determined by x-ray crystallography. Bfr forms a roughly spherical, hollow shell from 24 identical subunits, incorporating 12 haem groups. Structure of a monoclinic crystal form of cytochrome b1 (bacterioferritin) from E-coli Iron is stored as a hydrated ferric oxide mineral in its central cavity (about 80 Å diameter). The overall complex has cubic (432) symmetry. Each subunit includes a binuclear metalbinding site (the diiron site) linking together the four major helices of the subunit, which has been identified as the ferroxidase active site. Bfr from ''Pseudomonas aeruginosa'' (''Pa''Bfr), unlike other Bfrs, is found to contain two subunit t ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Nanoparticles

A nanoparticle or ultrafine particle is a particle of matter 1 to 100 nanometres (nm) in diameter. The term is sometimes used for larger particles, up to 500 nm, or fibers and tubes that are less than 100 nm in only two directions. At the lowest range, metal particles smaller than 1 nm are usually called atom clusters instead. Nanoparticles are distinguished from microparticles (1-1000 μm), "fine particles" (sized between 100 and 2500 nm), and "coarse particles" (ranging from 2500 to 10,000 nm), because their smaller size drives very different physical or chemical properties, like colloidal properties and ultrafast optical effects or electric properties. Being more subject to the Brownian motion, they usually do not sediment, like colloid, colloidal particles that conversely are usually understood to range from 1 to 1000 nm. Being much smaller than the wavelengths of visible light (400-700 nm), nanoparticles cannot be seen with ordinary ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Ising Model

The Ising model (or Lenz–Ising model), named after the physicists Ernst Ising and Wilhelm Lenz, is a mathematical models in physics, mathematical model of ferromagnetism in statistical mechanics. The model consists of discrete variables that represent Nuclear magnetic moment, magnetic dipole moments of atomic "spins" that can be in one of two states (+1 or −1). The spins are arranged in a Graph (abstract data type), graph, usually a lattice (group), lattice (where the local structure repeats periodically in all directions), allowing each spin to interact with its neighbors. Neighboring spins that agree have a lower energy than those that disagree; the system tends to the lowest energy but heat disturbs this tendency, thus creating the possibility of different structural phases.The two-dimensional square-lattice Ising model is one of the simplest statistical models to show a phase transition. Though it is a highly simplified model of a magnetic material, the Ising model can sti ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Cooperative Binding

Cooperative binding occurs in molecular binding systems containing more than one type, or species, of molecule and in which one of the partners is not mono-valent and can bind more than one molecule of the other species. In general, molecular binding is an interaction between molecules that results in a stable physical association between those molecules. Cooperative binding occurs in a molecular binding system where two or more ''ligand'' molecules can bind to a ''receptor'' molecule. Binding can be considered "cooperative" if the actual binding of the first molecule of the ligand to the receptor changes the binding affinity of the second ligand molecule. The binding of ligand molecules to the different sites on the receptor molecule do not constitute mutually independent events. Cooperativity can be positive or negative, meaning that it becomes more or less likely that successive ligand molecules will bind to the receptor molecule. Cooperative binding is observed in many biopolym ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Ultraviolet

Ultraviolet radiation, also known as simply UV, is electromagnetic radiation of wavelengths of 10–400 nanometers, shorter than that of visible light, but longer than X-rays. UV radiation is present in sunlight and constitutes about 10% of the total electromagnetic radiation output from the Sun. It is also produced by electric arcs, Cherenkov radiation, and specialized lights, such as mercury-vapor lamps, tanning lamps, and black lights. The photons of ultraviolet have greater energy than those of visible light, from about 3.1 to 12 electron volts, around the minimum energy required to ionize atoms. Although long-wavelength ultraviolet is not considered an ionizing radiation because its photons lack sufficient energy, it can induce chemical reactions and cause many substances to glow or fluoresce. Many practical applications, including chemical and biological effects, are derived from the way that UV radiation can interact with organic molecules. The ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Ferritin

Ferritin is a universal intracellular and extracellular protein that stores iron and releases it in a controlled fashion. The protein is produced by almost all living organisms, including archaea, bacteria, algae, higher plants, and animals. It is the primary ''intracellular iron-storage protein'' in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes, keeping iron in a soluble and non-toxic form. In humans, it acts as a buffer against iron deficiency and iron overload. Ferritin is found in most tissues as a cytosolic protein, but small amounts are secreted into the serum where it functions as an iron carrier. Plasma ferritin is also an indirect marker of the total amount of iron stored in the body; hence, serum ferritin is used as a diagnostic test for iron-deficiency anemia and iron overload. Aggregated ferritin transforms into a water insoluble, crystalline and amorphous form of storage iron called hemosiderin. Ferritin is a globular protein complex consisting of 24 protein subuni ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Fenton Reaction

Fenton's reagent is a solution of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and an iron catalyst (typically iron(II) sulfate, FeSO4). It is used to oxidize contaminants or waste water as part of an advanced oxidation process. Fenton's reagent can be used to destroy organic compounds such as trichloroethylene and tetrachloroethylene (perchloroethylene). It was developed in the 1890s by Henry John Horstman Fenton as an analytical reagent. Reactions Iron(II) is oxidized by hydrogen peroxide to iron(III), forming a hydroxyl radical and a hydroxide ion in the process. Iron(III) is then reduced back to iron(II) by another molecule of hydrogen peroxide, forming a hydroperoxyl radical and a proton. The net effect is a disproportionation of hydrogen peroxide to create two different oxygen-radical species, with water (H+ + OH−) as a byproduct. The free radicals generated by this process engage in secondary reactions. For example, the hydroxyl is a powerful, non-selective oxidant. Oxidatio ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Ferroxidase

Ferroxidase also known as Fe(II):oxygen oxidoreductase is an enzyme that catalyzes the oxidization of iron II to iron III: : 4 Fe2+ + 4 H+ + O2 ⇔ 4 Fe3+ + 2H2O Examples Human genes encoding proteins with ferroxidase activity include: * CP – Ceruloplasmin * FTH1 Ferritin heavy chain is a ferroxidase enzyme that in humans is encoded by the ''FTH1'' gene. FTH1 gene is located on chromosome 11, and its mutation causes Hemochromatosis type 5. Function This gene encodes the heavy subunit of ferritin, th ... – Ferritin heavy chain * FTMT – Ferritin, mitochondrial * HEPH - Hephaestin References * * * EC 1.16.3 {{enzyme-stub ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |